$100B Companies As Coordination Artifacts

And the general reasons why such companies seem to exist disproportionately in the Bay Area

My pal Freddie just sent me an interesting LinkedIn post from Rubén, an angel investor, which outlined the following:

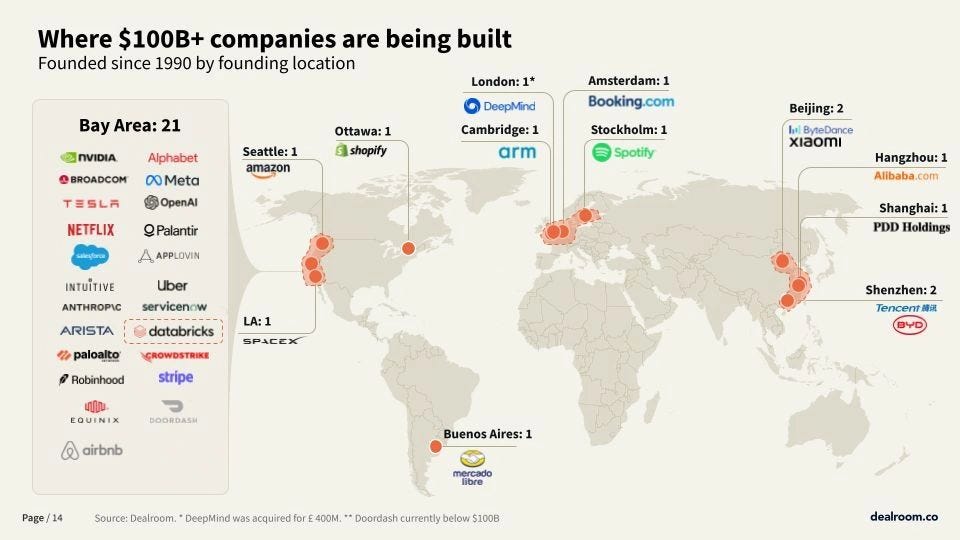

There’s even a cool map:

Fascinating!

And I want to dig into the question that Rubén asks:

What do you think explains this concentration most: talent density, capital, culture, or something else entirely?

The Wrong Explanation: Talent Density

The standard explanation for why West Coast Silicon Valley keeps doing absurdly well in the whole value generation game goes something like this:

The Bay Area has the best engineers, the most ambitious founders, the deepest pools of capital, and a culture that rewards risk-taking.

All of that is true, of course, although it is still grossly insufficient as an explanation.

Consider that if talent density were the decisive variable, Boston would dominate (and I’m biased, this being my intellectual home…). So would London (my second home), Paris, Berlin, New York, or Tokyo. I mean, these places are saturated with extraordinary people after all (like me, cough). They produce world-class research, serious companies, and durable global institutions.

What they do not consistently produce, though, are category-defining startups that can survive decades of ambiguity before they eventually, miraculously, compound into $100B+ outcomes.

That gap is important because it tells us very clearly that intelligence and ambition are not the binding constraints, as is often thought.

Through my work on institutions as coordination mechanisms, and despite many people believing the more interesting question to be “where do the smartest people live?” (I’ve already told you the answer to this), but “which systems can tolerate radical uncertainty, and for how long, without forcing early coherence or punishing failure?”

You see, extreme outcomes do not emerge from brilliance alone. In fact, they emerge from environments that allow incoherence to persist long enough for something new to take shape. And indeed, this is where most standard economic frameworks fail.

Human capital theory explains why skilled labor raises average productivity, but it does not explain why regions with comparable talent diverge so dramatically at the tail?

Agglomeration theory explains why firms cluster geographically, but not why a handful of those firms escape the distribution entirely?

Even innovation economics tends to focus on diffusion and spillovers, but never on the prolonged pre-market phase where prices are wrong, demand is unclear, and categories do not yet exist. (I dare someone to ask Mariana Mazzucato about her views on this…)

Category creation is not a market-clearing problem, alas, because it is very clearly a coordination problem that exists before markets can function at all.

In that phase, almost every signal that economists rely on becomes unreliable. As in, there are no benchmarks, no stable customers, no proven business models, and no meaningful way to price risk. Through this lens, then, the issue is not whether capital or talent is available (what most VCs wrongly talk about), but whether the surrounding system insists on resolution too early!

Most regions do, unfortunately. They demand legibility, predictable revenue, linear narratives, and early proof points in systematic fashion. These demands are understandable, of course, as they reflect the institutions built to allocate resources efficiently, not to explore the unknown. And yes, this now includes even Venture Capital!

But when demands for clear business models, predictable revenue, and conventional metrics are imposed too early, these demands collapse uncertainty before success has a chance to compound.

Systems that produce $100B companies are not distinguished by superior ability at picking winners; the logic needs to be inverted. What sets them apart is what they are better at not doing: they are better at not killing strange, fragile ideas while those ideas are still becoming intelligible.

In this way, the Bay Area’s advantage is not cultural mystique or superior genius (which is ironically nine-tenths of its lore); it is institutional patience! And this patience functions as the center of an intricate coordination regime, absorbing failure, tolerating illegibility, and allowing actors to remain inside the system after things go wrong.

That capacity is super rare, and it cannot be imported quickly or engineered through surface-level interventions in different geographies.

This also explains why so many attempts to replicate Silicon Valley stall. Because you can import venture capital, build incubators, teach entrepreneurship, and brand innovation districts. You will increase activity doing this. But unfortunately what you will not automatically change is the system’s tolerance for prolonged uncertainty. Without that, you get startups that do cool things, yes, not new and definitional categories.

And categories (not startups) are what compound into $100B outcomes.

If talent were enough, the geography of extreme economic success would look very different. The fact that it doesn’t is the clearest signal that something deeper is at work!

$100B Startups As Coordination Artifacts

$100B companies are not startups that simply succeeded at scale, and I want you to stop thinking of them as just “bigger” $10B startups.

They are, in fact, what I am going to call coordination artifacts: the visible residue of systems that miraculously managed to hold multiple, conflicting coordination problems together over decades of uncertainty!

Thinking about them this way immediately puts them outside most conventional economic and financial models and helps explain why they are so rare, and just so geographically concentrated.

There is a useful way to frame this through finance and statistics, even if most VCs avoid it (assuming they even understand basic statistics, of course). Standard financial models assume that value emerges from reasonably well-behaved probability distributions. In this way, risk can be priced, variance estimated, and outcomes cluster around a mean (this is, after all, the spine of financial markets!).

But $100B companies do not live in those distributions. They are extreme outliers. They are events in the far tail, and tail outcomes obey very different rules.

In statistical terms, category-defining firms follow power-law, not normal, distributions. In this way, a tiny number of outcomes account for a disproportionate share of total value creation, while the vast majority fail or remain marginal.

In such systems, average performance is pretty much irrelevant, because what matters is survival long enough to reach the right tail! The key variable is therefore not picking the best idea early, but staying in the game while uncertainty resolves and compounding has time to operate!

This language of “power-law” is now so familiar in venture capital, YET… most VCs don’t actually invest as if they believe it. In practice, ironically, VC capital is still allocated as though early signals are meaningful, and as if strategic coherence should arrive within the first ~2 funding rounds of a startup’s life. Portfolios are constructed around power-law rhetoric, apparently, but actually governed by normal-distribution instincts. (D’oh!).

The result is obviously a contradiction as investors say they are hunting the tail, but behave in ways that systematically truncate that tail they’re looking for. I mean, they frequently intervene early, force startups to pursue commercial outcomes, withdraw support after the first serious stumble, or shift attention toward what already looks like a clear winner. (They are a fickle bunch, these VCs!).

Optionality is acknowledged in theory and… destroyed in practice.

There are other ways to explain this financially!

Consider that real-option theory, for example, treats early-stage investment as an option on an uncertain future more than a discounted cash-flow problem. The value comes therefore from preserving the option while information accumulates. Exercising too early destroys optionality; just as abandoning too quickly forecloses upside.

Systems that produce $100B companies are those that stay on the side of deliberately keeping options alive, even when interim signals look irrational, inefficient, or embarrassing by conventional standards! (This is where the founder’s mentality, and lack of ego actually becomes incredibly important, despite VCs actually pursuing founders with enormous ego!)

So now, coordination becomes decisive.

To preserve optionality at scale, a system has to repeatedly select problems whose payoff is not immediately clear, while resisting all pressure to converge on what already looks sensible.

It has to form capital structures capable of sustaining long stretches of loss-making exploration without forcing premature coherence or financial discipline.

It has to do the incredibly hard work of socializing talent into working on things that do not yet make sense, training people to operate without benchmarks, stable career ladders, or clear measures of success. (Elon Musk, in this way, is in fact a genius).

At the same time, the system must absorb risk in a very particular way:

Category-creating firms are subjected to repeated stochastic shocks of

Technical failures,

Market misreads,

Regulatory setbacks,

Capital droughts,

Leadership crises

… all long before they resemble viable businesses. In a fat-tailed world, these apparent setbacks are often not signs of failure at all, but the unavoidable cost of learning in environments where the outcome cannot yet be known. Capital allocation regimes optimized for variance reduction treat them as reasons to exit. Systems optimized for tail outcomes tolerate them as part of the process. (And these two regimes are what I have discussed at length here).

Crucially, this hence requires legitimacy maintenance!

Belief has to be sustained among investors, employees, partners, and the surrounding ecosystem through long periods where nothing looks obviously successful and no standard metric validates the effort. Without that shared belief, coordination collapses before the upside even has a small chance of materializing. In fact, the need for this is often seen in a startup’s balance sheet through its marketing line items! Creating legitimacy is an urgent economic necessity in a pre-market environment.

A clear example of this need can be seen via SpaceX. For much of its early life, SpaceX looked indistinguishable from failure (and I am of the belief that it still does…). Today, still, rockets are exploding and timelines are slipping, while capital is being burned with little to show for it in terms of sustainable margin creation (although we’ll soon find out, if there’s ever an IPO).

By conventional financial or industrial metrics, the SpaceX project should have been terminated multiple times. What kept it alive was not evidence of success, but the continued legitimacy of the effort itself, via Elon’s cult personality!

Seen this way, the SpaceX story is illustrative of my larger point:

Most regions can manage two or three of the necessary coordination functions at once, and very few manage all of them simultaneously, but fewer still keep them aligned across cycles, leadership changes, macro shocks, and technological dead ends.

The Bay Area’s advantage is that it has built institutions (like capital structures, labor markets, reputational norms) that can preserve legitimacy long enough for fat-tailed outcomes to materialize, even when interim signals look totally fucking disastrous.

Most regions, meanwhile, do exactly the opposite. They apply financial logic designed for normal distributions to environments that are out of necessity governed by power laws. The result is this kind of systematic underexposure to the long tail. And since $100B companies are the tail, those regions never see them, no matter how much talent they have!

The Bay Area’s Real Advantage: Time-Scale Alignment

I wanna go one step further and now argue that the Bay Area’s competitive advantage isn’t actually any of what I’ve just mentioned just now, but something entirely new on top of those things:

It is time-scale alignment.

More than almost anywhere else, the region has achieved this alignment across the actors that matter (e.g. founders, funders, employees, and eventual acquirers) around a shared horizon that stretches far beyond the near term.

Time, in this sense, is a largely forgotten economic tool, and it always surprises me when people rediscover time in this way!

You see, most economic systems treat time as something to be minimized. Consider: shortened payback periods, accelerated returns, compressed investment cycles. But time can also be used strategically when extended, slowed, or deliberately held open, to shape outcomes.

The clearest demonstration of this came during COVID, when governments used quarantine not to eliminate risk (as many, many people believed!!), but to buy time. To flatten peaks, spread shocks, and prevent systems from breaking all at once. Time was deployed as an active stabilizing instrument, not as some sort of medical miracle.

The Bay Area applies the same logic in the opposite direction.

Rather than compressing uncertainty, it stretches it! Founders operate on decades rather than quarters, and capital is (supposedly, eyeroll) structured to wait rather than to force early liquidity. Employees tolerate long periods of illiquidity in exchange for participation in uncertain, asymmetric upside (I mean, look at Stripe!). And critically, failure does not eject people from the system.

This stands in sharp contrast to public markets and quarterly governance!

Public firms are structurally governed by short reporting cycles, benchmarked against peers, and evaluated through many metrics designed for mature, legible businesses. Perceived failures trigger scrutiny, discipline, and rapid replacement (the average tenure of a publicly listed Chief Marketing Officer is something like ~3.5 years!).

That logic is entirely rational for firms operating in known markets, sure. But when it is applied to pre-category or frontier-like environments, it systematically collapses the one thing you need: optionality.

The consequences are entirely predictable, of course, because we see them in all the places where $100B startups don’t exist! Systems governed by quarterly logic demand clarity before it can exist, and enforce efficiency before you even know what you’re trying to optimize for. Exploration of the “largest opportunity” has run its course before it’s barely started.

This is why failure in the Bay Area is tolerated so well… because it’s actually useful! People carry forward information, networks, and credibility even when individual ventures collapse. And the biggest resource of all, knowledge and learning, compounds at the system level rather than resetting to zero with each cycle. The ability of a founder to remain a respectable insider of the system after being wrong is proof of this culture.

In the world of $100B coordination artifacts, all of this is simply considered economic infrastructure. Time-scale alignment is what allows uncertainty to persist long enough for power-law outcomes to emerge. Without it, even regions rich in talent and capital are locked into short-term optimization, which systematically kills the tail.

Why the East Coast doesn’t produce these outcomes

The East Coast’s absence from this list is often misread as a failure of ambition or imagination, usually with delight by those on the West Coast. But.. it is actually neither. The East Coast is not stupid, or risk-averse, and it is certainly not capital-poor.

It is simply optimized for a different function!

(Consider that, loosely, the “top currencies” of the following places are different: Bay Area = startup founder; New York City = hedge fund manager; Boston = MIT professor, etc).

The East Coast dominant institutions are designed for allocation of resources (skills via universities, capital via investment funds) rather than startup creation.

They excel at totally different things: pricing risk, allocating capital efficiently across known categories, and enforcing discipline once markets are long established. In these places, namely Boston and NYC, reputation matters deeply, because reputation is how trust is transmitted in systems where capital moves quickly and mistakes are costly! (Funds are generational, and tenure is forever…). Here, valuation comes early, because valuation is the exact mechanism that allows coordination to scale in mature environments.

This works extraordinarily well for what those institutions are built to do. But… It is poorly suited to category creation.

Consider that finance asks, “What is this worth?”

While technology, at its frontier, asks, “What could this become?”

Those questions are not merely different, they actually operate on incompatible time horizons and demand incompatible forms of evidence.

In systems terms, the East Coast forces premature alignment, and projects are required to make sense early, to justify themselves in familiar metrics, to converge toward known categories before those categories actually exist. Uncertainty is treated as a problem to be resolved, not as a condition to be lived through for decades!

The Bay Area does the opposite. It keeps uncertainty open, which allows ideas to remain unknown longer, tolerating misalignment between effort and outcome, and delaying judgment in ways that feel inefficient by conventional financial standards.

That delay is what allows new categories to form at all.

$100B outcomes only exist on the far side of long uncertainty. Systems built to resolve uncertainty quickly, even if competent, disciplined, or well-capitalized, will almost always eliminate the tail before it has a chance to appear.

Hence, there are far fewer $100B companies on the East Coast.

China: Different Values, Same Systems Property

China’s handful of $100B+ firms are often described as evidence of convergence, as if they were cultural imitations of Silicon Valley! (I despise this framing). They are not.

In fact, China replicates the same underlying systems property (the capacity to sustain long-duration coordination under ambiguity), but by very different means!

If the Bay Area achieves this through private capital, social norms, and labor-market forgiveness, China does it through the state.

For the government, time horizons are enforced politically rather than negotiated socially, and similarly capital patience is guaranteed by sovereign backing rather than investor consensus. Talent flows are directed rather than discovered, which allows legitimacy to be backstopped by state authority rather than by market belief alone. (I’ve written about how the Chinese Central Bank works in similar ways, here).

The mechanisms differ sharply, but the underlying function is the same.

In both cases, the system can tolerate prolonged uncertainty without forcing early resolution, meaning that projects are allowed to remain weird for longer, and losses can be absorbed without triggering immediate forced exits. Thus, coordination persists even when short-term signals look bad or even terrible.

The differences between the Bay Area and Beijing are stark. Different values, different ethics, different tradeoffs. But they share the exact same ability to hold uncertainty open long enough for compounding to occur.

Europe’s problem is different, and harder

Europe’s failure to produce $100B+ category-defining firms is often attributed to regulation, fragmentation, or cultural conservatism. Those explanations are of course relevant, but a little incomplete.

Europe’s deeper problem is that it lacks both coordination regimes. (Yes, if possible, the actual reason for Europe’s lack of humungous growth is actually worse than you may have already thought)...

Unlike the Bay Area, Europe does not have a private ecosystem capable of sustaining radical uncertainty for decades. Capital is fragmented, risk is reputationally expensive, and failure often results in permanent exclusion and morbid embarrassment (a cultural trait which still surprises me to this day!).

Labor markets are protective, yes, but rigid, meaning that upside is capped early, while downside is socialized. Ugh. The result is way too much caution that is rational at the individual level but fatal at the system level.

At the same time, unlike China, Europe also lacks a state willing (or, cough, able) to impose long-horizon coordination at scale. Industrial policy exists, but it is constrained by insane bureaucratic governance, short electoral cycles, and many legal frameworks designed to prevent abuse rather than enable sustained experimentation. Programs are carefully scoped, heavily justified upfront, and quickly withdrawn when early results disappoint. (I won’t list examples here, for fear the list doesn’t end…)

In effect, Europe absorbs uncertainty from both sides, but resolves neither! Markets demand early legibility while states demand early accountability. Between them, there is almost no institutional space where the unknown can persist long enough for a new category to form!

This is why Europe excels at incremental innovation, scientific excellence, and high-quality execution, but consistently fails to translate those strengths into global category leadership. The issue is not talent, ambition, or even capital (as I’ve said many times, Europe has plenty of this), it is that Europe lacks a system capable of sustaining coordination when markets cannot yet and when the future cannot yet be priced.

Seen this way, the comparison is not about which economic development model is preferable. It is about which systems can still do the hardest thing in the modern political economy: hold uncertainty open long enough for something genuinely new to emerge.

Forgiveness As Infrastructure

There is one variable that almost never appears in economic analysis, and yet actually determines whether extreme outcomes are possible at all: institutional forgiveness.

I’ve mentioned it briefly already, of course.

$100B systems require it as a form of innovation infrastructure. They must forgive failed founders, burned capital, socially illegible people, wrong bets made early, and repeated attempts by the same actors. Without that forgiveness, experience drains out of the system precisely when it becomes most valuable.

This is really about little other than retaining accumulated information. Category creation is an iterative process, and most of what matters is learned through failure, despite what Mazzucato and other innovation economists might infer. When institutions punish deviation too quickly, they do not just terminate projects; they importantly eject the people who now understand why something didn’t work!

Different institutional domains handle this very differently, of course.

Venture capital, at least at its best, is unusually forgiving. A failed startup does not automatically disqualify a founder from future funding, as Adam Neumann can attest to (!) in some cases it actually increases their credibility (!!). Capital is written off, and lessons are absorbed, and experienced actors are allowed to remain inside the ecosystem as a Father Figure type persona with important knowledge.

This is an implicit recognition that learning in fat-tailed environments is expensive, and that discarding experienced participants is economically irrational.

Academia occupies an uneasy middle ground in this whole affair, unfortunately. Early exploration is tolerated in theory, but the forgiveness window is narrow and front-loaded. Miss a grant cycle, fail to publish quickly enough, or stray too far from the paradigms du jour, and your credibility goes to zero. The system forgives briefly, before it reasserts discipline and makes you persona non grata. The result is rigor and depth in the industry, but limited capacity for sustained, category-breaking work outside a handful of protected niches. (Hence, academia publishes very little of note these days).

Government is the least forgiving of all, and this is where industrial policy runs into trouble. In the public sector, failure is reputationally radioactive. Programs that do not work are treated as evidence of moral incompetence rather than as information! Careers end, budgets are cut, and lessons are rarely institutionalized. As a result, industrial policy is often designed to avoid visible failure rather than to maximize learning, which is clearly just dumb. Projects are over-specified, milestones are front-loaded, and ambiguity is minimized; all precisely the opposite of what category creation requires.

This is why so much industrial policy fails: because it is structurally intolerant of uncertainty. The political system demands early proof and linear progress, with defensible metrics. But pre-category environments simply cannot supply those things! When the first attempts stumble (as they almost always do) the response is permanent retreat rather than iteration.

Most regions punish failure in this way because their dominant institutions cannot afford prolonged ambiguity. Reputation systems within these institutions, capital allocation mechanisms, and governance structures are built to close uncertainty quickly. The moment something looks wrong, coordination snaps shut.

The consequence is therefore an unspoken ban on ideas exploration. But… exploration is where new categories are born! Without institutional forgiveness (unevenly distributed across venture, academia, and government) even well-funded industrial strategies will produce some activity, but without compounding.

This Concentration Will Intensify

It is tempting to believe that these dynamics will eventually diffuse. That as knowledge spreads and capital globalizes, more places will begin to produce extreme outcomes. However, the evidence actually points in the opposite direction.

As technologies grow more complex and capital more cautious, coordination costs rise, not fall. The demands therefore that are placed on systems increase faster than their capacity to absorb uncertainty.

Complex technologies require increasingly longer development cycles, deeper integration across domains, and higher tolerance for interim failure. At the same time, capital has become more disciplined, more benchmarked, and more sensitive to reputational risk. Even Venture Capital shies away from risk!

This toxic combination narrows the set of environments capable of sustaining long-horizon experimentation to a hair’s width. Fewer systems can tolerate prolonged uncertainty, and fewer places allow repeated failure without exile. Thus, fewer institutions are willing or able to underwrite unknown outcomes for decades.

The result is a bifurcation.

Execution continues to globalize, of course. Talent, manufacturing, and deployment disperse across borders and regions. But category creation, these $100B companies, becomes more centralized, not less, as it concentrates in the handful of systems that can still hold uncertainty open long enough for compounding to occur.

Everything else meanwhile will optimize for survivability and efficiency, and in doing so, systematically eliminates the extreme upside.

So, if I had to say this as plainly as possible:

The Bay Area doesn’t produce $100B companies because it has more talent or capital, because a ton of other places have that too. It produces them because it is one of the last places with an institutional stack capable of holding radical uncertainty open long enough for compounding to occur.

Everything else is downstream of that.

The institutional forgiveness angle is brilliant because it reframes failure as accumulated information rather than reputation damage. Most ecosystems optimize for avoiding embarassment which systematically kills the tail before it appears. The Bay Area tolerating founders who burned capital and staying in the game isn't cultural niceness, its economic infrastructure for preserving optionality. Treating time as a strategic variable that can be extended rather than minimized is such a simple insight but totally counterintuitive to quarterly-driven systems.

this is spot on