Did ChatGPT Write This?

Or maybe you're just a bad fucking reader?

Sinéad again.

I loathe to write about Artificial Intelligence (specifically, OpenAI) twice in a row. But alas, here we are.

This week I sent someone a poem. Their feedback was cutting:

“Looks like ChatGPT wrote this.”

A few months ago, I wrote and illustrated a poetry book for a friend’s son. It took me a month to do that. Her response?

“Nice work, ChatGPT!”

And when I tell people I’m a writer, their immediate reaction is more often than not, some version of:

“Oh, cool, so you can just use ChatGPT to do that for you, right?”

I cannot tell you how much these throwaway comments make me want to put down the pen, tear up my notebooks, and die.

So this piece exists mostly as a time-saving device. A URL to send people the next time they flatten my effort into algorithmic output, or wink at me when I discuss book deadlines.

Here, in one conveniently compiled rant, I’ll outline:

Why I think or care about this

What the writing process actually looks like

What ChatGPT can and cannot do

Why you’re all just bad fucking readers

ONE: WHY I CARE

I’m going to start with a small secret that most people have absolutely no idea about. And only because credibility seems to require data these days:

I am a prolific writer.

In the last ten months, since January:

I’ve written more than 700,000 words

90% of which is fiction

I’ve written seven (soon to be eight) novels; last year it was four.

They span five genres (next year I’ll add a sixth).

I write under multiple pseudonyms, each with its own distinct brand.

(And please don’t ask me to disclose them. You’re wasting your time. Only my agent and my business partner know.)

In fact, to date, I’ve met exactly one person who I suspect might write as much as I do: Cass Sunstein. (Though, to be fair, he has research assistants and co-authors. I do not.)

So trust me when I say:

Very few people think about ChatGPT, its role in writing, and its implications for publishing as much as I do.

TWO: WHAT WRITING LOOKS LIKE

There are really two parts to writing, and both form the real and hard work of writers.

First: what the process actually is when you’re trying to make something of value: a poem, a novel, an essay.

Second: how, over time, you learn to make your work better.

Now, I want to very importantly preface this with the fact that I have fallen into the role of a writer in much the same way as Alice discovered Wonderland. I did not study English Lit at Yale (in fact, I only read textbooks until a couple of years ago when I decided I should read a fiction book before writing one); I did not do my Creative Writing MFA at Columbia, or at all; I did not work at The New Yorker doing menial tasks in the hope that an editor would one day spot my talent.

Instead, I took the Forrest Gump approach, as I do with many things: I quite literally started writing one day and didn’t stop.

2.1 The Creative Process

On Daily Routines

I wrote in a book recently that, contrary to common belief, writing is less about emotion and more about devotion.

To write is to enter into a kind of faith. In the strange, mercurial system through which something arrives out of nothing. (Every single day I think about how this, alone, is just an extraordinary thing!)

At the scale of writing I do, you learn to build the trust in yourself that if you keep showing up, the words and their meanings will eventually appear, and even somewhat consistently.

And out of necessity, and in doing so, you create the rituals that coax that outcome closer: having your first words committed to paper before an exact moment on the clock every day; a teacup that has seen you through your best and worst books; the exact level of ambient noise that seems to open the trapdoor between thought and language.

All of this becomes an obsessive kind of superstition. I went through an awful three months, unable to write, last year. Unrelatedly, my friend Tomasz gave me a new teacup for my birthday. The first time I used said teacup, the words flooded back to me. Coincidence? Almost certainly. But it doesn’t matter; I now only use that cup when I’m writing, and when I’m not, it gets hidden away.

In other words, being a writer and trying to produce books is like being the government trying to produce innovation: All you can do, unfortunately, is create the conditions through which the creativity can allow itself to arrive. The rest is “wait and see”. Trust the process. Etc, etc.

For me, this looks pretty simple: Every single morning, between the hours of 6-7am, I’ll have committed my first words to paper, at the same desk in the same house. I will stop only once I’ve reached my target goal. Which, by the way, is ambitious.

My daily word count when I’m in “writing mode” is 15,000 a day. When I’m off-duty, it’s about 2,000-5,000 per day. In writing mode, the most I ever wrote in a day was around 20,000 words. On a very bad day, it can be as low as 3,000.

My schedule is important, too. When I’m writing, I aim for a 15,000 word day, with three days on/ two days off. For some reason, this works extraordinarily well for me. So I stick to it.

People often ask: wow, I had no idea you’re a writer, don’t you do a ton of other stuff? Yes, most of what people would consider to be my “job” are things I do between the hours of 1pm and 10pm.

There is a great deal of sacrifice that comes with this writing malarkey.

Kafka’s The Metamorphosis

On Planning

Hate to say it, but 90% of the heartbreak of having to re-write an entire book (yes, I’ve done this plenty of times) is because I fucked up the planning stage and jumped into writing too early.

In fact, I will not even contemplate starting a book, article, or poem unless I have an extremely clear understanding of what it’s going to be. I have to understand it inside out.

Most people that think “writing is very hard”, do so because they struggle with what they are trying to write; not how to write.

I typically spend 2-3 days doing intense “world building” for a book before I commit to writing. This involves character development, their names, personalities, what they wear, places, maps, languages, time era, novel forms of government, the specifics of how technologies and science might work, political systems. On, and on, and on.

I will create a 50-100 page “Story Bible” about the world in which the story exists. (This becomes incredibly useful, in fact, if you do screen adaptation work). And reference it constantly throughout writing.

If this is something smaller like a simple poem, I will do a very miniature version of this and create a short video in my head of the world or emotion that I’m trying to put down on paper. And then quite literally write out that video, before hashing out the syntax.

On Writing

The crux! There are three different levels at which I write. The sentence level; the chapter level; the book level. These are the ways in which you have to constantly keep your shit together, and congruency needs to exist between all three, at all times, for multiple layers of storytelling.

For example, in a book, you have the primary narrative arc, with usually 2-3 supporting arcs, that must all intersect, create tension at different points in the book, before finally all resolve roughly at the same time.

So at the end of my writing day, before wrapping up, I edit for these main points.

But more than just me going through them, I do a hell of a lot of Beta Testing. On… everything. I’m extraordinarily data-driven about how I write. This is mostly because I write across so many genres, each with their own reader cultures and likes/dislikes, that I need people to tell me what works and doesn’t.

As I write, I will constantly put something out to a group of beta readers. Did you like this sentence? What about this word? This direction, or that? On a scale of 1-10, what was your likability of this phrasing? This ending? Etc. My last book did terribly with Beta testing: one person loved it, one person refused to read more than a chapter. Clearly: more data = better.

[Hence, by now, I’d like to subtly introduce the idea that writing is not a solo activity; there’s a whole fucking circus of people that are constantly up your ass while you’re trying to pull this off: agents arguing about the type of book that can feasibly be sold; editors requesting you change how the whole thing is written, such that it can be marketed differently; readers that disagree wholeheartedly with the first two perspectives; business developers who need storylines and characters long before they’re set in stone to begin merchandising design and media assets.]

When it comes to something smaller like poems, or a book of poems, I usually write and edit at the word and stanza level. In some ways, poems are harder than books, because you have to really understand the single core point you’re trying to get across, given you have very little space for confusion. You often only have, at most, one additional subplot to strengthen that story.

2.2 Improving your craft

This, for me, is where most of the excitement lives. When I am not in “writing mode”, I am in “learning mode”.

Again: I do not have an MFA or equivalent in writing, so the onus of self-improvement is largely a self-directed one.

My “big idea” in this area is simply the following: that there are many kinds of writers, and I want to exist in a small subsection of the best of them.

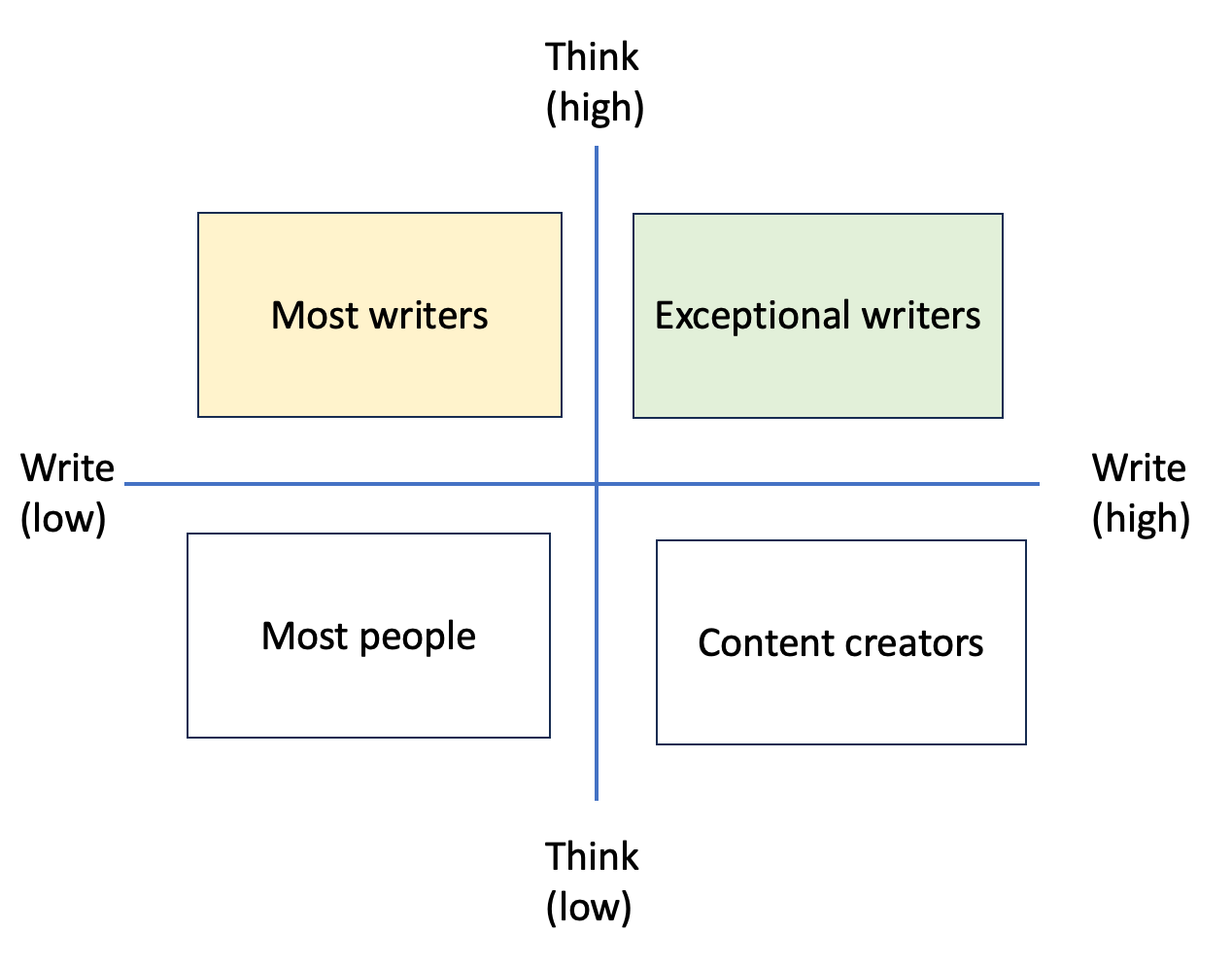

I am going to summarize them here; the only two important ones being in the top quadrants in terms of how much thinking and how much writing people do:

Most of the writers that I meet are low output, high thinkers. In that they will think, and think, and think, endlessly. In bed. In bars. On deserted islands. At writing retreats. Anywhere, it seems, but at a desk, with a laptop, where they can convert thinking to doing.

To be exceptional, you have to live in the top-right quadrant: where both ideas and technique belong to the top 0.01%. And this is, ambitiously, where I’m trying to extend myself. (Whether it ever materializes is another question entirely.)

Being an exceptional writer is like being an exceptional concert pianist.

You don’t spend twenty years laboring over a single sonata just to perform it one night at the Berliner Philharmonie. You spend all day, every day, practising. Scales, drills, chord progressions. Left hand, right hand. Classical, jazz, romantic, experimental.

The goal is fluency: to move so effortlessly across form that you can stop thinking about it and simply do it.

And that type of fluency requires two things: (1) having a wide understanding of form; (2) a hell of a lot of practice across those forms.

1. Understanding Form

When I’m not writing, I’m learning about writing; just as obsessively as I write. And like my writing, this has structure too. I pick something up, underline it, research it, highlight it, and read it ten times over: inside out and upside down.

I have a syllabus for genres that I will very methodically work through via very old books. Very new books. A lot of poetry. Translations: dozens of them, because translation teaches you the small alchemy of meaning: why this word and not that one? Why this rhythm and not another? I’ll read The Paris Review, The New York Review, film scripts, TV scripts, documentary scripts. Science fiction. Biography. Graphic novels. Horror.

It’s all part of the same practice.

And it’s exceptionally fun. I can take a line, a sentence, or the mechanics of a phrase and roll them into a ball of dough and pull, fold, stretch, test them for their elasticity, to see how far they can go before they break.

Sometimes it’s just a single word that I’ll carry around for weeks, that I’ll totally fall in love with, holding it up to different genres and characters like a fabric swatch, waiting to see where it fits.

If it fits at all, that is. Sometimes, it won’t fit anywhere. In fact, most of the time, writing is an experiment of null results; work that goes nowhere. Publishing work is a theology of outliers. (But again, it’s the process that’s really important, so you accept the pain).

2. Practice across forms

This is where my plentiful novel writing comes in handy. And where I’ve been incredibly lucky.

I have several writing “voices”; as should most good writers. And these have been curated by working with different editors (again, very lucky). My editor at the FT changed my style, in the same way that my editor at The New Yorker helped me develop something completely different again.

Different genres, too, will force this upon you. As will the creation of different types of characters and places. One of my books switches between three different languages, which is really testing!

The point is that you need to practice. And lots of it. And not mindless word creation, either. For e.g.: for several years I had my own column (again, grateful). However, my work there wasn’t edited. Those were, very sadly, lost years. Output without learning.

You need an editor to challenge you. Friction is good, which is why Substack is bad, and I’ve kind of gone back to writing pieces for editorial outlets again.

Yes, friction may be miserable, but it is so utterly productive.

Other than editors, this is why beta testing is so damn useful in writing. Without it, you’re just throwing hundreds of thousands of words into an abyss. Particularly in publishing, where there is already a weak feedback loop (one writer and one editor to millions of readers; a bad ratio), it’s a long feedback loop too: I can write a book, and only two whole years later when it gets published, do I get reader feedback.

So in those two years, between writing and understanding how it was received? Most writers, weirdly, have no feedback.

THREE: WHAT CAN ChatGPT DO?

Ok so here’s the part you were waiting for.

What can ChatGPT do, when it comes to these writing activities?

Honestly, very little. And here’s why.

There’s a reason I just spent so much time telling you how hard it is to be a writer.

Because those are the human things a machine can’t do.

It can’t sustain devotion. It can’t build rituals, or superstition, or faith. It doesn’t wrestle with self-doubt, or wait for meaning to arrive, or rewrite a paragraph fifty times until the rhythm feels right in the mouth, only to change it back to the original.

That’s what writing is. Not words on a page, but the long and highly irrational act of using language to create something from nothing.

What it cannot do

ChatGPT, as most LLMs, are probabilistic outcome generators. You ask a question, and it creates the “average” answer for that question. Some topics are easier to get good “average answers” from than others, clearly.

The complexity of what I can do in ChatGPT at the moment really exists at the sentence and paragraph level, for the main reason that it struggles to coherently write more than ~800 words on anything.

So when it comes to writing books, well, let’s look at the math. My last book was 125,000 words across twenty-eight chapters. In ChatGPT terms, that’s 156 legible parts. What fucking psychopath is going to break down a story narrative into 156 parts; also considering that these parts must still be enjoyable for the reader?

The other big issue is that ChatGPT cannot concurrently connect those ~800 pieces very well. While it is capable of doing it at the main narrative level, when you want to think about secondary or tertiary plots (which yes, you do), then forget it. Even if it can handle some concurrent storytelling briefly, it very quickly gets confused and will change your character’s personality, or hair color, or basic plot outline.

“You’re right! That character is still alive, after all! Good catch!

In short: it’s far faster, easier and more stable to write a book by not asking ChatGPT to write it for you.

Do I think this will change over time? Hell yeah, I do! I think ChatGPT will get extraordinarily good at being able to compete with the top left of the aforementioned quadrant: “Most Writers”.

And this belief stems, again, from the fact that it uses probabilistic reasoning to write; and most of its training data = most other books = mostly shit.

What it can do

Ok. So that’s what it can’t do. But is ChatGPT useless? Never going to be good?

No, not at all! I am not an LLM doomer. Quite the opposite, in fact!

With my writing hat on, I use it all the time. But just not in the way that people assume, and not by asking it to write stuff for me.

Now that you know what constitutes the practice of a good writer, it should be fairly obvious about how I use it. For learning. For researching genres, and materials, and even for mundane things like first passthrough editorial work (although, actually, I have nearly stopped this entirely now; it’s too unpredictably bad at picking up on spelling or grammar mistakes, and there are four different types of editors alone that work on a single book, meaning that editing is too specialized for it!)

But the most important thing I use ChatGPT for? A mental sparring partner. All day, every day. It helps me clarify my own ideas, challenge my assumptions, and push back when no one else will. (You just have to force it to do this, a lot.)

And often, having a well thought through idea is exactly what differentiates you as a writer.

In the same vein, when I’m writing, I will often play with individual lines or expressions that don’t quite sit right. For example, I can take a line and ask ChatGPT to consider rewriting it in the style of various different authors. (This prompt, in itself, however, requires a good understanding of literary structure.)

Whether or not that is how they would write it, who knows. But for me, this process can allow me to understand the first principles of what I’m trying to write by looking at counterexamples. It can give me clarity on identifying what the main part of my argument or expression really is (again: most of the difficulty of writing is in not knowing the point being made; not the way in which it is made).

Why do people think it’s ChatGPT?

I have spent the last twenty-four hours ruminating on this. Both times that my work was recently commented on as ChatGPT-created, the work was in the same genre: Absurdism.

I have long been obsessed with Absurdism. And in fact, I have spent most of this year entrenched in the literary spectrum of Absurdism through to Surrealism (and not just in literature, although mostly).

This Absurdist-Surrealist spectrum is what I have chosen as my home “style” that I am building out, through rigorous studying and practice. And this began, by the way, long before I started writing like this.

As long as I can remember, I have always been a “ditty” writer. Short, funny, weird poems. Usually as gifts. For any occasion, from birthdays to breakups. In fact, when one friend found herself particularly heartbroken, I recorded the ditty to a beat, and made a music video, and released it as a song. I found myself during the first lockdown with only a banjo, and so everybody got a ditty-banjo birthday tune. You get the point. When it comes to simple Absurdist poems, I can hit a home run quite quickly.

Absurdism, for me, isn’t a style. It’s a worldview. It’s how I think.

It’s how I make sense of the small insanities that everyone else seems to accept as normal. It pokes holes in the grand performances of modern life: “meetings” that exist mostly to kill time, corporate language that is used in lieu of importance, the endless theatre of productivity. For me, absurdism is like watching people dance in a nightclub with the music muted: everyone is moving with conviction, but to nothing at all.

Absurdism, I suspect, is the only sane response to a world that has forgotten how strange it actually is.

It is also a genre that has been built on carefully over the decades. So what might sound like a simple piece of absurdist writing to an untrained mind, might actually be steeped in something profound, that is invisible to most readers who are not looking for its subtext.

Take, for example, one of the most famous pieces from my favorite Absurdist writer, Daniil Kharms (who is Russian, and for which I learned enough Russian language just so that I could understand the difficulty of this exact translation):

Blue Notebook 10

There was a redheaded man who had no eyes or ears. He didn’t have hair either, so he was called a redhead arbitrarily.

He couldn’t talk because he had no mouth. He didn’t have a nose either.

He didn’t even have arms or legs. He had no stomach, he had no back, no spine, and he didn’t have any insides at all. There was nothing! So, we don’t even know who we’re talking about.

We’d better not talk about him any more.

So. This seems pretty simple, right? Could ChatGPT do this? Well. Yes, it can create the words. But no, it can create neither meaning nor importance. And in my genre, this is an extremely meaningful piece of writing.

The most simple expression of Absurdism comes from simple juxtapositions.

Daniil Karms, as himself.

For e.g.: there’s a little boy who lives across the street from me, who asked his father, one day, about a friend who left the house: Where did he go?

To which his father answered: “Out and about!”

The boy replied: “Oh! Can you take me there, later?”

When his father brought him to the park later that day, the boy started to cry.

“I thought you were taking me to Out and About! Not to the park where we come all the time!”.

This inspired several of the poems in the book that I made for my friend’s baby son.

Here are two lines from a poem in that book:

“A-CHOO!” came the first cloud, and oh, what a sight!

Down poured marshmallows, all fluffy and white!

Upon first reading, the simplicity of the words may be all you see: a children’s poem that rhymes. Easy!

But in fact, what is much harder to do, is to put a shit ton of weird images and noises and rhymes together in a structured way, over many lines and stanzas, that creates meaning that sits at one or two levels deep.

(The meaning of this poem, by the way, is actually about the interactiveness of the natural environment: rain, like clouds, is not something that purely happens to us, but rather that we can choose to engage and live within weather too!).

I am in no way trying to insinuate my children’s book is akin to Kharms’ prolific work, but nevertheless, at least some of my creative currency, built over many years of hard work, was what created it.

Long story short: I suspect, although I do not know, that when people read something that seems easy on the outside (even if only because it is so well practiced to seem easy in the first place), that it has been written by ChatGPT.

Because how hard could it be, at the end of the day, to put together a few lines that rhyme?

FOUR: MAYBE YOU’RE ALL JUST BAD FUCKING READERS

When someone tells me that ChatGPT wrote what I wrote, I get really fucking sad.

And the reasons why should now be obvious.

I happened to get the “This is ChatGPT” message on the same day that I was finishing a 95,000 word book. I woke up deliriously tired from hammering out my book, saw the message, and really had to force myself to sit down and write anything at all that day.

The whole thing feels pretty damn pointless when I keep hearing this comment, over and over, that ChatGPT writes for me. With a wink. And a nod.

Does this mean I am against ChatGPT as a tool in writing? No, not at all! In fact, the opposite. Does this mean that I wish ChatGPT hadn’t stolen work that I’ve written to train itself? In premise, yes, but even then… how much do I really care?

Because like most things, if I want to be in the top echelon of writers, I should just get used to having competition nipping at my ankles, regardless of whether that’s a real person or an algorithm, right?

But even that, in principle, doesn’t bother me as much as the deeper question:

If the algorithm now sounds like me, and I sound like the algorithm, does it still matter that I wrote it at all?

Does it matter if I write anything?

Because if the world can’t tell the difference, then what exactly am I proving by writing a million words a year? Other than making myself very tired and making my skin age prematurely, what’s the bloody point?

Especially if all it takes is one lazy assumption to flatten months and years of hard work into a single shrug:

You just typed a few prompts, right?

And now, after I’m done being sad, I get angry.

Ok. Maybe not necessarily angry, but I’m certainly salty. I mean…

Maybe the problem is not ChatGPT.

Maybe the problem is YOU, the reader.

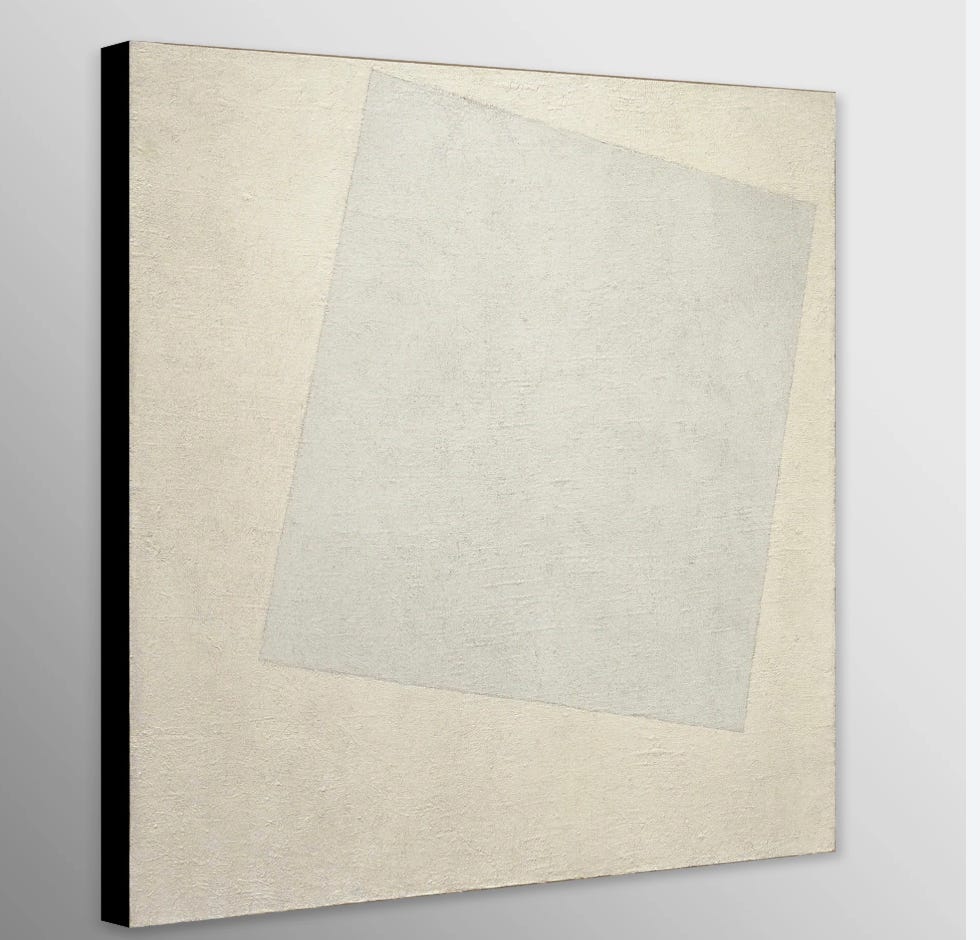

Maybe there is nothing that I can do about the fact that you cannot discern the difference between a white canvas and Kazimir Malevich’s infamous White on White painting (another Russian, this time Suprematism, not Surrealism).

White on White (1918)

My friend Claire from the Whitney Museum of American Art was giving me a tour a couple of years ago, when she said something I felt was profound about contemporary art:

“It’s completely fine that people come to the museum and don’t understand it; that’s their prerogative. But they cannot say it’s bad. Not understanding it does not mean that it’s bad; they simply have no reference to judge it. Instead, they should say: I don’t understand it, but somebody who does, thought it was good.”

My point is this:

When people say “That looks like ChatGPT,” they’re not insulting the work, but rather revealing their own blindness to subtlety.

That they can’t see the difference between a blank canvas and Malevich’s White on White; between something empty and something deliberately minimal, existing with tension and intent.

That’s what good work often is: it looks simple, but it’s not. It’s tuned down to the millimeter. It’s every choice of word, rhythm, pause, and restraint working invisibly in concert.

Anyone can paint a white square. Very few can make it mean anything.

So maybe the issue isn’t that my work sounds like ChatGPT. Maybe it’s that the quiet precision of good art has started to sound inhuman.

(Or maybe, you know, you’re all just… bad fucking readers.)

Brilliant. This is such an interesting follow-up. I'm so curious about human ingenuity's future.