From Creative Destruction to… Destruction

David Einhorn’s warning that markets aren’t innovating, they’re just vaporising capital with lazy PR

Hey, Sinéad here! What ensues is a long rant about how fucked up both capital markets’ and governments’ allocation of resources (namely capital) is right now.

TL;DR: Hedge fund manager David Einhorn’s recent phrase “capital destruction” isn’t just bearish market chit chat. Unlike normal losses, which teach and recycle, capital destruction deploys capital with neither return nor legacy. Governments are destructing capital when they brag about dollars “funded” rather than projects completed. Corporates are doing it when their capex announcements and bad PR stand in for strategy. Investors do it when management fees matter more than exits. The result? Capital allocation gets mistaken for achievement, spending becomes performance, and the feedback loop that makes capitalism work starts to destroy everything in its way. In Einhorn’s world (which, by the way, is also ours), that isn’t just inefficient, it’s existential.

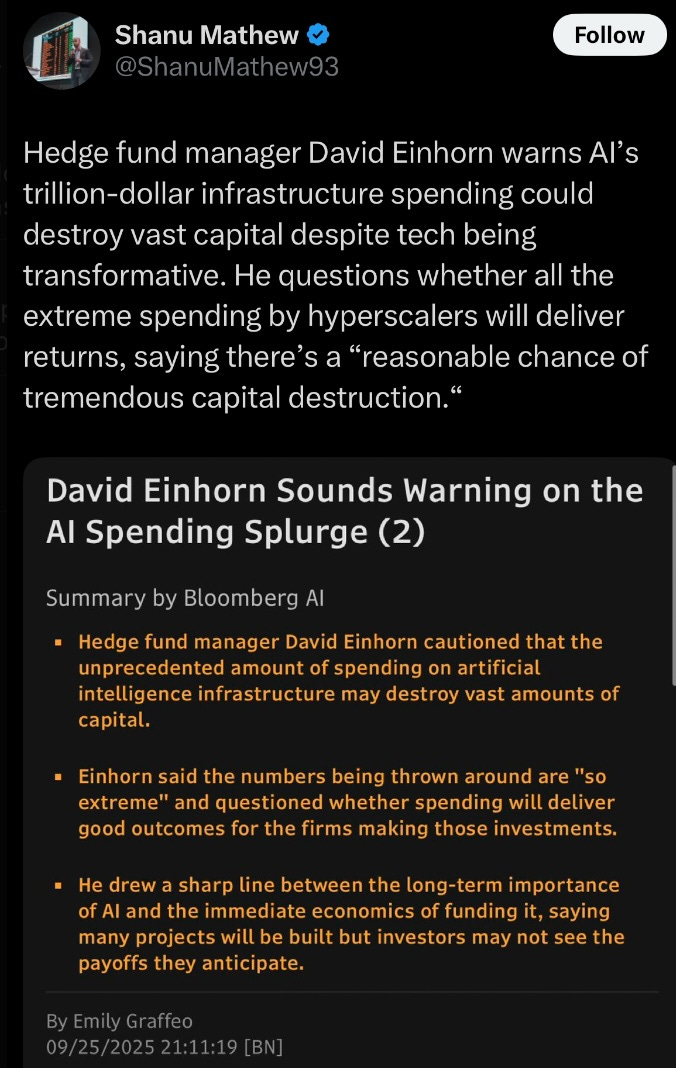

I was boarding a flight from Rome to London on Friday evening when this tweet caught my attention:

The phrase that David Einhorn used stopped me dead in my tracks… To the extent that I sent it to Alex Chalmers (my lovely other half of But This Time It’s Different), in a panic to discuss.

For over two hours at 35,000 feet, and long after I landed, I obsessed over two words in particular: capital destruction.

Why? Because “capital destruction” is such a… strange phrase. It’s not “losses”, a word used frequently by hedge fund managers. It’s not “froth”, which feels appropriate for today’s moment, and it’s not even “overbuild”.

Capital destruction.

That wording landed hard because it suggested something more than a sector in distress or a valuation reset. I realized by the time I was on final descent that it suggested a breakdown in how capital itself is being treated.

I’ll come back to why that distinction matters. For now, what struck me was this:

If destruction means capital that produces nothing, the only “value” in capital allocation lies in the act of spending itself.

Consider that for:

Governments: it’s not the creation of infrastructure but the press release, the spending program announcements, the ability to say billions have been “funded.”

Corporates: it’s not the M&A deals or the new business lines, but the analyst call, the headline capex number, the marketing lore.

Private investors: it’s not the carry, but the management fees; the guarantee that as long as capital is moving, they get paid, regardless of what that capital produces.

In all three cases, the real economy is secondary. The act of deploying capital becomes the achievement, and the only people it reliably serves are the ones doing the deploying.

That’s the cultural shift Einhorn is naming.

Governments now measure “success” by how much money is disbursed rather than what gets built, announcing funding as though allocation were completion. Markets are drifting into the same logic, treating capex announcements or GPU orders as proof of leadership.

In both cases, allocation is being mistaken for outcome:

Governments: if the money is allocated, the problem is solved.

Markets: if the money is allocated, the future is secured.

Capital is no longer a means to create value; it has been redefined as the product. Which is why “capital destruction” panicked me into realizing that this is more than just a bearish soundbite.

Instead, it reads like a warning that the system is beginning to celebrate the performance of investment rather than its purpose. And as such, once that drift takes hold, the feedback loop that makes capitalism work doesn’t quite disappear, but it abso-fucking-lutely dulls.

In other words, the very mechanisms capitalism depends on begin to… how to say this… shit the bed: price signals blur, discipline (what discipline?) vanishes, and our collective resource allocation system (gradually at first, then all of a sudden) disappears.

Why Say “Capital Destruction”?

As I mentioned, Einhorn could have said the AI boom risked “losses,” or that hyperscalers might “overbuild.”

And these terms wouldn’t have made me blink, because they would have slotted neatly into the usual business cycle headlines: investors take a hit, valuations reset, balance sheets hurt for a while, and then the system learns and moves on.

I mean, consider that losses aren’t a flaw of capitalism; they’re its reason for being.

Simply: the system advances by punishing bad bets and forcing adaptation.

Examples: A failed business model gets exposed and an incompetent CEO is fired. An overheated market is corrected and investment funds shut down. Painful? Yes, but information-rich. That’s the entire point.

Even apparent excess can become useful over time; bubbles aren’t necessarily bad if pointed in the right direction! The dot-com fiber glut wiped out investors in 2001, but a decade later those empty cables became the cheap plumbing of the modern internet.

The word “destruction” though signals something outside of the usual business cycle, which is why this has irked me so much.

The word matters because it signals something… darker?

Recall that Joseph Schumpeter calls capitalism a process of creative destruction: old companies and technologies die so better ones can take their place. Brutal, but ultimately productive.

Well, through that lens we can understand that capital destruction is the mirror image: it’s the destruction without the creation (!).

Money vaporizes, but nothing grows in its place. No useful legacy, no new industry, no information gained. Just stranded capital and empty capacity.

(I am not, by the way, saying that I necessarily agree with Einhorn; this is actually something that I believe Alex and I are aligned on– Einhorn may in fact be in some ways wrong here. I am merely pointing out that his belief of destructionism is constructive for understanding the current economic landscape).

And… To be clear and fair, capital destruction doesn’t appear to just be a private market problem.

Because it turns out that governments are doing exactly the same thing… A topic of conversation with a senior policy-maker while in Rome this very week! Governments are guilty too of measuring “success” by dollars spent rather than outcomes delivered, announcing spending as if allocation were completion. And nowhere is this clearer than in the big U.S. industrial bills, which I’ll discuss in a moment.

Economists, as always, have many frameworks for all of this. Allow me to roll out some relevant ones to sound smart:

Goodhart’s Law: We all know and love this one, which tells us that when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. Dollars spent, capex announced, GPUs ordered… they all become corrupted proxies which reward the appearance of participation rather than actual results.

Hyman Minsky: Very in vogue these days, and describes how finance evolves from hedge (you can pay everything), to speculative (you can cover interest but not principal), to Ponzi (you can’t even do that, you just hope someone else steps in). AI infra spending has that Ponzi vibe: a trillion dollars deployed not because the economics make sense, but maybe because Trump has normalized adding large numbers of zero’s after spending targets.

Baumol’s cost disease: Explains why the destruction problem sticks: inputs rise endlessly, outputs stagnate, but we still get to call it “progress” because the spending looks impressive (to everyone except us, of course, because we have uncovered their plans…)

Put these together and Einhorn’s word choice comes into focus.

“Losses” would have implied a normal cycle which is painful, but self-correcting. “Destruction” implies something else: that the feedback loop is broken; losses and overbuilds leave behind information, sometimes even infrastructure. Destruction leaves behind nothing.

This is what Einhorn is really warning about:

Capital has stopped being treated as scarce and purposeful and instead has become ornamental. It’s a diagnosis that the capitalist system itself has lost its meaning.

The Paradox: Shouldn’t Einhorn Welcome Losses?

This was what initially baffled me flying somewhere over France: If other investors are pouring capital recklessly into AI infrastructure (overpaying for GPUs, building data centres they can’t fill, electrifying grids without knowing who will pay for the power) shouldn’t that be good news for David Einhorn?

If his peers are misallocating capital, their eventual losses should make his discipline look sharper. Because when benchmarks fall, his relative performance rises. In theory, he wins by default. He should welcome this behavior!

But… that logic only works in a system where discipline still matters.

Losses only benefit the cautious investor if they are punished and priced in. If capital destruction becomes normalised (or, if spending itself is mistaken for strategy, if disbursement is mistaken for progress) then the scoreboard itself breaks.

Dumb money isn’t punished. Smart money isn’t rewarded. So… Einhorn, the “smart money in the room”, loses.

Einhorn himself put this bluntly at a conference earlier this week. Asked if the market is still broken, he didn’t hesitate. “Oh, very much so,” he said. Then he drew the line that explains everything: it depends what you think a market is for.

To distill this thinking:

If the purpose of a market is to allocate capital, reward things that have good returns, punish things that have bad returns, and in the process push companies to be more efficient… then the market, he argued, is “ever more broken.”

But if the real purpose now is entertainment and short-term scorekeeping, to let people amuse themselves and enrich themselves by trying to guess what a stock will do in an hour or even three nanoseconds, then the market works brilliantly.

The trouble is that the second purpose has swallowed the first. Traditional valuation talk, Einhorn joked, now has about as much bite as “shouting the emperor has no clothes at a nude beach.” Everyone knows it. Nobody cares.

And that phrase “nobody cares” is the spine of his warning.

Alors, there are two ways to read Einhorn’s decision to say this out loud.

The first is instrumental: Hedge fund managers don’t usually talk much; information is their edge. So when they do, it’s mostly to move a market in their favour. Einhorn built his reputation this way, shorting Lehman Brothers ahead of the 2008 crisis while publicly making the case for its collapse. It’s possible “tremendous capital destruction” is simply another turn of the wheel: a way of talking down a sector he believes is overextended, while his book is lined up to profit.

But… there’s also a second reading, and it speaks to something deeper. And this is what I want to emphasize.

Einhorn represents an older worldview in which capital is sacred: a scarce resource, entrusted to investors to be stewarded carefully and productively. When he says “capital destruction,” he isn’t just forecasting bad returns. He’s saying the system is abandoning its function. Capital allocation (the sacred central act of capitalism ✝️) has been severed from the responsibility of generating value.

Capitalism only works if losses matter. If nobody cares, then losses no longer discipline, no longer reallocate, no longer teach. They stop being tuition and start being… destruction.

So let’s go back to Hyman Minsky briefly. As long as the game keeps going, even the most reckless players can look like winners.

For a value investor like Einhorn, this is existential.

His entire philosophy rests on the assumption that markets, eventually, rediscover reality. That value gets rewarded and poor allocation gets punished. But if destruction is tolerated, even celebrated, then discipline itself becomes irrelevant. The careful investor doesn’t just underperform but becomes obsolete.

In this new market world, even being right stops mattering.

That’s Why Einhorn Cares. But Why Should We Care?

Because it’s pretty simple…

Once capital itself becomes the outcome, the economy slides into a theatrical shit show. Spending is no longer the means to progress; it is the performance of progress.

For me, this is clearest in government, and something I’ve been thinking about professionally for the last eighteen months.

Let’s go back to Biden’s industrial policy for a moment, which was pitched as the most ambitious since the postwar era. Sure. Even I bought that (at the time).

Between the CHIPS and Science Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, more than $2 trillion is being mobilised to reshape the U.S. economy. The intent was serious: build semiconductor capacity, accelerate the energy transition, restore domestic manufacturing.

But as I mentioned, the criticism is also serious: the scoreboard is spending, not actualizing.

White House fact sheets boast about dollars “funded,”; grants are announced before factories are built; subsidies are counted as wins even when plants are years away from production. The problem is that allocation itself became the KPI, with little tracking of productivity, cost per job created, or long-term competitiveness.

Now let’s pause for a moment and consider:

Where are we seeing this play already, with huuuuge consequences?

China.

China is the larger-scale cautionary tale. Industrial subsidies now exceed 4% of GDP, and the IMF estimates they shave another 2% a year off productivity. The result isn’t innovation, but glut. EVs, lithium, semiconductors, real estate, …. (I could go on)... all suffering from chronic overcapacity, deflation, and collapsing margins.

What Xi Jinping has called “involution competition” is just a polite label for Einhorn’s “capital destruction” with Chinese characteristics (i.e. insane scale): for example, factories kept alive not because they are viable, but because subsidies make their survival a political imperative.

Europe, as always, adds a third flavour. Brussels’ rhetoric of “strategic autonomy” (if I have to hear this phrase one more time…!) has been mostly reduced to subsidy one-upmanship between member states. France announces billions for hydrogen, Germany counters with billions for chips, and the Commission waves through state aid on the grounds of competitiveness. The metric is not results, but symbolic parity. “We, too, are spending.” (But never, ever, ever, creating real plans for delivering).

And yes, we already know that private markets, once known for their fierce efficiencies, are beginning to mirror the same rotting behaviour.

The hyperscaler capex race is the corporate analogue of the subsidy race. Amazon, Microsoft, and Google compete to announce the largest AI infrastructure investments, each one eager to look dumber yet more inevitable. The numbers themselves become the narrative. Demand, monetisation, and unit economics trail far behind (or simply don’t exist).

And so… who cares?

Well! (I say, with exasperation). When spending is the scoreboard, incentives warp:

Politicians optimize for big allocations that can be announced within an election cycle.

Bureaucrats optimize for headline numbers rather than productivity or spillovers.

Companies optimize for capex size, not utilisation or return.

Investors optimize for AUM and increasingly large investment fees.

The system produces a Black Mirror, black-comedy theatre.

But… It doesn’t have to be this way! History shows that industrial policy can work, but only when subsidies are tied to performance and capability-building rather than judged by the size of allocations.

DARPA in the United States = the classic success story, funding high-risk R&D in computing, networking, and aerospace, etc, with a tight focus on spillovers and technology platforms; the outputs were transformative, from the internet to GPS.

Postwar Japan and Korea used state-directed credit with export discipline = firms had to prove competitiveness in global markets to keep support, which forced them to innovate and scale.

But there are just as many failures (womp womp womp):

Japan’s “convoy system” in the 1990s protected banks and firms from competition, keeping them alive through subsidies and credit guarantees; the result was zombie companies and two lost decades.

China today is repeating the mistake at scale: subsidies so large they create chronic overcapacity, with firms competing not to innovate but to survive subsidy-driven races to the bottom.

Biden-era programs risk falling into the same trap: Subsidies for EVs, hydrogen, and solar under the Inflation Reduction Act could entrench incumbents, inflate costs, and underdeliver on productivity if not paired with rigorous accountability.

The Consequences

If Einhorn is right, the consequences ripple far beyond AI data centres or hedge fund returns. Capital destruction doesn’t just erase money; it corrodes the system that allocates it.

For investors: the danger is distorted benchmarks and mispriced risk. If spending itself becomes the measure of strategy, then discipline is no obviously longer rewarded. Benchmark-relative LPs keep allocating to funds that burn cash, because their peers are doing the same. Asset managers applaud capex because capex has become the KPI. Price signals weaken, and the craft of investing drifts into marketing.

For governments, the danger is what we can see in China: stranded projects and political backlash. Subsidy races create headlines in the short term but cynicism in the long term, when factories remain unfinished or productivity gains never appear. Industrial policy framed as “dollars allocated” eventually erodes legitimacy: citizens see money go out the door, but not enough come back in the form of jobs, infrastructure, or growth. The result is public fatigue, scepticism of government competence, and a harder road for any future state-led strategy.

For society, the danger is the hollowing out of progress itself. Innovation gets crowded out as capital is funnelled into performative projects instead of hard problems. Long-term issues (climate resilience, infrastructure renewal, frontier science) lose out to sectors better at producing shiny capex numbers. Trust in markets decays as people rightly sense that capital has become self-referential. And eventually, capital itself flees: investors retreat to short-term arbitrage, governments struggle to finance ambitious programs, and risk appetite for long-horizon projects withers.

In other words: it’s a race to the shitty, shitty bottom.

Everyone ends up poorer, even if a verrrrrrry tiny number of people get deliriously rich on the way down.

And this is the systemic meaning of Einhorn’s phrase.

“Capital destruction” isn’t just about AI chips or data centres. It’s about the possibility of capitalism hollowing itself out; of celebrating the performance of investment while forgetting its purpose.

It was only somewhere between taking off in Rome on Friday evening and last night in London that this clicked. My week’s conversations about defense economics and government spending plans, the Biden White House boasting about dollars “funded,” Einhorn’s phrase about “tremendous capital destruction”, the focus on Chinese involution competition: these aren’t separate stories.

They are the same story told over and over again.

TL;DR —> Governments are mistaking disbursement for industrial strategy while markets are mistaking capex for inevitability. And both are conflating capital allocation with outcome by treating capital itself as the product while rewarding the appearance of progress over its substance.

That’s the reason Einhorn’s words felt heavier than a routine market warning as I sat dismally looking out of the window at the clouds on a Friday evening.

He isn’t just calling a sector top within a heightened business cycle, but alluding to a much deeper danger: that we are building an economy where money is celebrated for moving, but not for creating.

And here, in this new economy, the function of capital has been finally abandoned in favour of its performance.