How To Become a Mathematical Genius

What mathematics reveals about intelligence, intuition, and modern failure

TL;DR: What many people experience as a “cognitive limit” or the edges of their own intelligence is actually just a representational limit: it’s when we use a specific way of thinking, but apply it to the wrong types of problems. This makes us think we’re stupid, when actually we’re not!

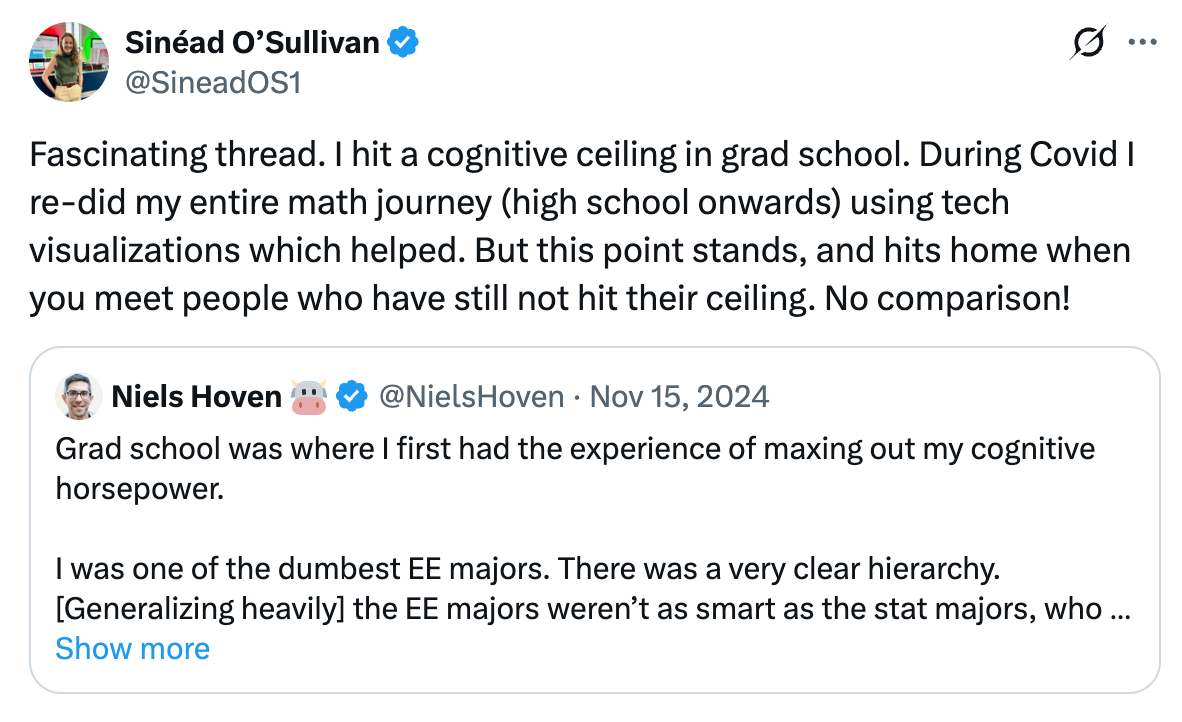

I want to go back and admit that I was very wrong about something I wrote in a tweet a couple of years ago, relating to mathematics and our so-called “cognitive limits”:

Namely, that I had hit my cognitive limit back in grad school as I tried to muddle my way through multiple PhD math classes on very abstract topics, including a rather unfortunate, semester-long journey through the mathematical theory of black holes (this video is actually a great taster of what that involved!).

My tweet is basically saying that at a certain stage, I (like many others have done before me), realized that I had hit my brain’s computational limits, in the same way that a runner might eventually hit their physical limits. And that at this stage, it was incredible to watch those around me continue to advance to higher and higher cognitive functions even when I had stalled, because I realized that there is a very fundamental difference between me, and them.

At that time, it’s safe to say that I believed two things:

That there is in fact a hierarchy of what is “cognitively challenging” (I still believe this)

That there are cognitive limits to who can pursue the topics within the most challenging domains (I no longer believe this)

Now, because a lot of us are woke now, you’re not supposed to say things like: Person A is smarter than Person B because the former has a degree in Electrical Engineering and the latter has a degree in Comparative English Literature.

(This assumes that Electrical Engineering is harder than English Lit, and while that is an entirely different essay, let’s just assume here that it’s true.)

But what you can actually say (even if people find it offensive) is that Person A has tested much more rigorously the limits of their brain’s computational limits than Person B; and while we cannot know for sure who is smarter, isn’t it a general trait of people with high brain capacity to pursue the testing of such limits?

Anyway, I digress. The point I am making is that some problems are simply harder than others, and as you move along the spectrum of the difficulty level of problems, fewer and fewer people are able to tackle them.

Many people are able to compare two of Shakespeare’s works. But now think about the Riemann Hypothesis, also known as the world’s hardest math problem, which proposes that all non-trivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function lie on a specific vertical line in the complex plane. Very few people can think about this problem, and even fewer still can solve it (none!).

Ok, so that covers the hierarchy of problems and the difficulty of solving them.

Now I want to discuss my earlier interpretation of who can solve these problems.

I’m going to use math as an example, but as you’ll see, the takeaways are the same regardless of topic!

Understanding Cognitive Limits

In order to discuss the ways in which I hit my own cognitive ceiling in math, which hugely shaped my opinion of those who were able to bypass theirs, it’s worth looking at how math has largely been taught for the last… forever.

From very early on, mathematics is presented to students (and to itself) as a ladder of formal techniques.

In this way, we learn symbols long before we learn the meaning behind them. In fact, only a tiny number of people will ever learn the actual reasoning behind things like “sin” and “cosine” or the real relevance of pi or i.

I truly pity the baffled twelve year olds who cannot fathom why anybody might care about knowing the value of the constant which is equal to the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter, to over one trillion digits beyond its decimal point (pi).

This is usually the stage at which you’ll hear a student say: “I’m dropping my math classes, because it’s not relevant to what I want to do in the future.” Touché!

And unfortunately, this is because we learn math procedures before we learn about its underlying purpose. These procedures, if you get good at doing them, allow you to be rewarded for correctness, speed, and rule-following! I.e., you get to become “good” at something, even if you’re not entirely sure what that something is!

Going through high school, I was consistently the “best” in my class at math, simply because I could repeat the randomized patterns of trigonometry faster than anybody else. And this was fantastic, of course, but just as long as nobody ever asked what any of it really represented.

Teaching mathematics in this way is very similar to teaching a language (because math is a language). Don’t ask why one verb is irregular and different from the rest; it just is. Memorize it!

This way of learning produces a very particular experience of “what constitutes difficult”. And as the notation becomes denser and the objects get way more abstract, progress begins to feel like raw mental exertion. Proofs get longer (they can indeed span multiple pages) and symbols proliferate to the extent it feels like you’re writing in mandarin. You begin to miss the days where you could draw a “square” or “cube” to help figure out what problem you were actually trying to solve, because you realize there is no representational form in the number of dimensions you’re trying to solve to visualize your problems anymore.

So at some point, the only way forward seems to be “thinking harder” in order to “understand better”.

And eventually, when that “thinking harder” effort stops working, it is natural to conclude that you have hit a cognitive limit.

That’s pretty much what happened to me.

At a certain stage, I realized: I have no idea what problem I’m even trying to solve! What the fuck is this? My papers seemed to be symbol-salads, for the sake of solving a human-created symbol-salad. The arbitrariness of it all had finally caught up with me. Why do I care if someone decided that a equalled b? And that if I inverted them, and did some cool trick, a could also not equal b? And that we would give this trick a name? And then use it on other tricks to create more rules? And more tricks, and more rules…

What the fuck did any of this mean?

And it seemed very unfair to me that all around me were people who had some sort of intuition that I lacked when it came to understanding such things. I couldn’t tell if they were actually more stupid than me because they were not questioning the existential nature of why things seemed to just go this way, or if they were lightyears ahead of me, because they didn’t need to question it; they simply understood it.

“Ah, but what if you used a möbius transformation on the planar subset, to transfer it into the objective plane?”.

When these suggestions on my problems worked, I was always left with the thought: How is all of this organized in their mind? And why is it so different to mine?

Of course, one of the sad realities of university is that in order to get a job, you need to get good grades. And to get good grades, you need to be in the top 5% of your class. And to do that, you have to take subjects that you find easy enough to crawl to the top of. Which means that a university is ironically no place to pursue wild passions and interests in which you are not already well versed.

So I did what was appropriate at the time: I stopped taking the classes I found most interesting, and optimized for the ones I could reasonably pass, while watching my peers move eloquently past my level of thinking, to work on increasingly abstract and nonsensical problems.

And I came to terms with the fact that I was simply just not smart enough to do the same. I had hit the limits of my cognition!

Good Mathematician, Bad Mathematician

I still hugely enjoy mathematics. Unfortunately for me, though, my favorite sub-genre of mathematics that I like to read about is also possibly the “hardest” or most abstract: topology.

Here are some of the questions that this field concerns itself with:

When are two things “the same” in a deep sense?

A teacup and a doughnut are topologically the same because each has one hole. You can deform one into the other without cutting or gluing. A sphere, which has no holes, is fundamentally different. This is a totally crazy reorientation of how we perceive the world! (And some of the maths behind the cognition I discuss here).

What is a hole, really?

A hole isn’t a thing you can point to, because it’s defined by what isn’t there! Topology gives precise meaning to this absence, this anti-thing, which is then a thing, because of how it changes everything around it! (In this sense, you may understand better now my love of Kazimir Malevic!)

What is forced by structure alone?

Some outcomes are inevitable given the way things are connected. The reverse is also true. Topology is very good at proving impossibility: showing that something cannot be done, no matter how clever a solution may seem to be. This has incredibly important and amazing applications to more “real world problems” than can be discussed here.

I tell you this ^^ only in the hope that you, too, will start to love topology! But let’s get back to my main point…

As I’ve become more detached from the stress of needing to be “good” at math, I’ve found myself increasingly more curious about how mathematicians actually think. One of my good friends is an extraordinarily gifted mathematician in the same field I was in, making for a rather uncomfortable comparison of my objective failures in applied statistics, and watching him work when we were in Chicago at UChicago was endlessly fascinating.

His “big idea” is arguably Nobel worthy.

You see, many statistical problems are solved by modeling the actual problem as a shape of many dimensions, and then bending, stretching, or pulling that shape to poke around for solutions (this is, essentially, where my work intersected with topology). What my pal Guillaume does is slightly different, with massive implications! He turns the potential solutions into shapes. These shapes are significantly smaller and have fewer dimensions, and can be solved far faster. An absurdly elegant concept that importantly: others had not considered!

(I remember the day he came to my house from his office, put his briefcase full of his scribbled proofs on my kitchen counter, and pulled out a bottle of whiskey to celebrate this piece of work!).

And it fascinates me: where did this idea come from? And what led him to think of the problem in this very specific way?

This line of questioning actually asks a far bigger question:

What does it mean to be “good” at math? Or “good” at anything?

Because I was good at math. Until suddenly, one day, I wasn’t good at all. What had changed: was it me hitting my cognitive limit? Or at a certain stage, had the process of “doing maths” become something else entirely, for which I had no training? For a long time, I suspected the former.

And then, the biggest question of all: if it could even be the latter, this means that the task of being a “good mathematician” had indeed changed. Could I become, again, a good mathematician?

I have spent much of the last year, in fact, thinking about this exact thing: can I train myself to be a topologist, and a good one, at that? And if so, how?

Thinking Slow to Work Fast

One of the most compelling interviews I’ve ever read of another human being is that of famed Fields Medal mathematician June Huh, interviewed by my favorite math magazine Quanta, here. Please, please, please, read it. Here are some parts of the interview that made me radically re-think the entire idea of structural cognitive limits:

He tried his best to avoid math whenever possible. His father once tried to teach him out of a workbook, but rather than try to solve the problems, Huh would copy the solutions from the back.

and

The work showed that “you don’t need space to do geometry,” Huh said. “That made me really fundamentally rethink what geometry is.”

and

“I have this math competition experience, that as a mathematician you have to be clever, you have to be fast,” he said. “But June is the opposite. […] If you talk to him for five minutes about some calculus problem, you’d think this guy wouldn’t pass a qualifying exam. He’s very slow.”

There’s just so much to unpack.

In particular, consider that (1) he was once bad at math, but is now good; and (2) he works at a pace that is so slow, that his colleagues thought he was quite literally stupid. These two points lead me to believe that I was right in my earlier thinking that, at a certain stage, the task of being a mathematician changes suddenly once you get to a certain conceptual point, and with that point comes a new set of skills, and hence a redefining of what “good” looks like!

More importantly, for me, this hints at the idea that: perhaps I had not hit my cognitive limit when taking PhD classes? Perhaps what I hit instead was the natural end-point of one type of maths, and the beginning of another.

(The mere suggestion that I might actually be smarter and more capable than previously thought is an obviously very optimistic one, but let’s run with it, because the narcissist inside me is now very excited!).

So, if being fast, and having rote memorizations of functions and tricks and shapes and what-not is no longer what makes someone a good mathematician, then what is?

If, like me, you read a lot about these peculiar mathematicians who solve big problems, you’ll notice something quite interesting about these radical intellectuals in their youth:

June Huh trained as a poet.

Maryam Mirzakhani (who tragically died far too young) was a painter.

Keith Devlin trained as a musician.

The most important people in the field of mathematics consider themselves to be an artist first, and a problem solver later. This is a radical departure from the “I’m left/ right brained” nonsense we tell ourselves.

Consider the interview by the New York Times of Terry Tao, who is arguably the finest living mathematician, and perhaps the best the world has ever seen:

Early encounters with math can be misleading. The subject seems to be about learning rules — how and when to apply ancient tricks to arrive at an answer. [...] Really, though, to be a mathematician is to experiment. Mathematical research is a fundamentally creative act. Lore has it that when David Hilbert, arguably the most influential mathematician of fin de siècle Europe, heard that a colleague had left to pursue fiction, he quipped: ‘‘He did not have enough imagination for mathematics.’’

It is clear, after going down this rabbit hole, that these people are undoubtedly extraordinarily intelligent. But the missing ingredient that separates a Fields Medalist winner from me, I suspect, actually has much less to do with horsepower and cognitive ceilings, and more to do with… creative intuition.

Bird Lament

I was running through Hyde Park recently in a trance-like state thinking about some of Terry Tao’s work, and the incredible way in which his mind seems to work, when my Spotify shuffle played a song I had not heard in years: Moondog’s “Bird Lament”.

Now, if you do not know of Moondog, or of his music, stop what you are doing right now and give this a listen. I came across his music in a Brooklyn apartment a few years ago, when I was drinking wine on the floor of a rather eclectic couple: my friend, a fashion historian and her partner, an MIT scientist with a sharp focus on graph theory, who proceeded to pull out musical instruments before the evening all got a bit hectic. I digress...

Just as a mathematician is actually an artist who uses their art to solve problems in, say, topology, it occurred to me while running that Moondog, too, could be a mathematician in reverse: an artist who uses the art of topology to create music (this is in fact a piece I am in the process of writing at the moment in more detail, more on this later).

This thought stayed with me for the rest of the day after my run had finished, only to that night find a very timely piece written by mathematician David Bessis on his substack, arguing roughly the following:

The economist Daniel Kahnemann’s Nobel-winning theory that humans think both “fast” and “slow” is incomplete: humans also think “super slow”, and this type of thinking is what drives advances in fields such as mathematics.

Needless to say, I was extraordinarily excited to read such a theory! Because it confirmed what I was beginning to heavily suspect, and what Terry Tao had told the New York Times previously:

The true work of the mathematician is not experienced until the later parts of graduate school, when the student is challenged to create knowledge in the form of a novel proof. It is common to fill page after page with an attempt, the seasons turning, only to arrive precisely where you began, empty-handed — or to realize that a subtle flaw of logic doomed the whole enterprise from its outset.

There is in fact a second type of mathematics, and these awful people in the awful faculties of these awful universities have kept this a secret! That the very nature of mathematics changes drastically, without warning!

Seen through David’s theory, my “cognitive limit” was nothing more than the fact that I was trying to apply my “thinking fast” brain (which I had over years optimized highly specifically for maths!) to what had suddenly become “thinking super slow” problems.

And after much thought and introspection, I am going to now diverge slightly from David’s framework to propose my own (although I have to admit that I have not yet had the time to read David’s book on this exact topic, which he admittedly knows infinitely more about than I do). Not because David is wrong of course, but because what I experienced did not feel like a matter of speed at all.

It felt like a change in kind.

From my own experience, with respect to learning, there seem to be two fundamentally different ways people come to understand a subject, and hence to solve problems:

Symbolic thinking: This is when people familiarize themselves with a domain through notation, rules, and procedures;

Structural thinking: This is when people create an internal sense of what can change in a system and what cannot without it breaking. It’s a type of intuition around constraints and failure modes, and only after the underlying structure is already understood, are notations and rules introduced.

These two styles are optimized for very different tasks, and as I learned in grad school, modern education overwhelmingly trains only one of them: symbolic thinking.

Symbolic thinking is extraordinarily effective for learning what already exists! It thrives in environments where the structure of the problem is known in advance, and hence the rules are stable, and correctness can be externally verified easily. In maths, this is done through coursework, problem sets, and rote learning techniques. So it’s easy through all of this to know if you’re “good” or “bad”; because your take-home final exam will tell you so, numerically.

Structural thinking, on the other hand, becomes essential precisely when none of the above is true. It is the way you are required to think when the structure itself is unclear, or when the goal is not to apply a known method but to discover whether a solution is even possible! (Again, topology is often about what is missing, not what is there!). Consider the following: the only reason I know Terry to be a good mathematician is because one of the very, very tiny number of people who can vouch for his math “working” says so. Thus in structural thinking, it’s much harder to know what “good” looks like, and how close you are to it.

And the difference between these two types of thinking is stark.

I can almost immediately tell when I’m talking to someone who is a symbolic thinker, instead of a structural thinker. In finance, they’ll tell you they’re a PE investor but then won’t understand why interest rates are important. In economics, they’ll tell you that growth is decelerating but won’t actually understand what “growth” inherently is. And in mathematics, they’ll sound like me.

In simpler terms: all the gear, but no idea. The words sound right, and the facts are there, but none of the underlying dynamics will make sense to drive third- or higher-dimensional insights that are used to creatively work in areas without structure.

And I felt this viscerally, but couldn’t explain why, in grad school. Because right around the PhD level of math is when the task is to stop “solving problems” and starts being about inventing them. This is an entirely different proposition.

Crucially, learning also feels completely different in these two modes, and this is ultimately what I’ve been thinking about in this last year.

Symbolic learning is really about accumulating gold stars and progressing step by step. It’s creating a level of deep familiarity with the process. And then structural learning feels like the total opposite: mostly confusion and repeated failure. From the inside of this transition from one type of thinking to the other, I will say without a doubt that the feeling is of overwhelming intellectual collapse. Total and utter stupidity.

By contrast, the people that I was watching move past me quickly at grad school, already had a deep exposure to structural thinking in other parts of their lives. I, unfortunately, had not.

And this is why so many people experience what they interpret as a “cognitive limit”, in the way that I did. I was not “running out of intelligence”, something that I think sounds so stupid now; it was far from it! I was actually just being asked to switch representational modes without even being told that such a switch existed! Or, importantly, how to make it.

I want to be more concrete. Here’s the difference in the types of problems I was trying to solve, without having had the adequate training:

Symbolic thinking:

Solve this differential equation:

y’ + y = ex

The structure is already known.

I’m rehashing an established argument

Being “good” means being heavily practiced with developed speed

Structural thinking:

Does an object with these properties even exist? Is there a continuous function with property X but not property Y?

I don’t know whether I’m trying to construct something or create a proof of impossibility

Being “good” means being patient, tolerating slowness, being mostly wrong and having intuition

Here are examples outside of maths:

To radically summarize how I have perceived the world’s problems:

There are two types of thinking that can solve two types of problems:

Symbolic thinking solves problems inside a known structure;

Structural thinking is what you need when the structure itself is the problem.

And we live, overwhelming, in a world of structural problems right now.

Who Gets To Solve Hard Problems?

To get back to where we started: who gets to solve hard problems?

For many years I believed it was the freakishly intelligent people with seemingly endless cognitive horsepower that had not even come close to nearing their own limitations. But actually, now I think it depends on the types of problems.

Hard problems, as you move through the hierarchy of difficulty, are increasingly in the “structural thinking” domain: what comes after neoliberalism; should we still engage with capitalism; who should we decide the winners and losers are in this new era?

So perhaps then the best way to become a good solver of hard problems is to become like June Huh, Maryam Mirzakhani and Keith Devlin: read a few books, play a bit of music, recite some poetry and hope for the best!

Indeed, I have noticed that my own thinking has drastically changed since I started this experiment of trying to “think like Terry Tao”, which is a mostly useless journey because he really is singular, and this is an entirely biased experiment. But in the process of allowing myself to take strange turns and pick up interests in various topics (the Ottoman Empire, surrealism fiction, architectural education), I have noticed a marked increase in my ability to think structurally about increasingly abstract topics, even as I’ve spent less time doing anything that looks like formal theoretical work.

And this leads to an somewhat distressing conclusion.

The kind of training required to develop structural intuition (June’s slowness, Keith’s breadth, Tao’s intellectual risk-taking, and long periods without measurable output) is almost perfectly incompatible with the incentives that govern modern careers.

Today more than ever, success requires early optimization for symbolic performance: get the highest grades, choose the safest subjects, attend the best university, secure the best internship, never pause, never allow your attention to drift, never specialize too late, never be unclassifiable.

This system is extremely good at producing people who can operate fluently and be quickly promoted inside existing structures. It is far less good at producing people who figure out what happens when those structures disappear entirely. Who can grapple with existentialism. And our world has become overwhelmingly defined by what is not there instead of what is. It is defined by topology.

But… who is the topologist-cum-politician of our time? Nobody that I can think of.

So in one sense, I feel I’ve answered a question that chased me for years: how does one become a great topologist, or the next Terence Tao?

But unfortunately, answering that question only raises the next, even harder question.

In a world that increasingly rewards symbolic thinking and optimization, will we still allow the conditions under which someone like Terry can exist at all?

This symbolic vs structural distinction explains so much about why people plateau in unexpected places. I've watched this exact thing happen in tech, where engineers who crush leetcode interviews completley fall apart when asked to design systems that don't exist yet. That insight about modern careers optimizing for early symbolic performance hits differntly when you realize we're basically training people to be really good at the wrong thing for the problems that actually matter.

In symbolic thinking we mirror other people's compressions, often and typically without fully understanding ourselves. This is the more common way of thinking, see Gabriel Tarde's "Laws of imitation"

Cognitively speaking it is lower effort; it can be viewed as a survival mechanism, efficient use of limited resources