How To Fix A Crackhead Economy Addicted To Free Money (ii)

A Framework for Building a Coherent Post-Neoliberal Economy

This piece is part of a series that has been shared more times than I could have imagined! Here’s the full series:

Part 1: Identifying the real problem of our crackhead economy

Part 2: A framework for fixing our crackhead economy

Part 3: How to actually implement such a framework.

In Part I, I performed an autopsy of the issues with the forever-bailout economy. Now I’ll look at the actual fix.

But before I do, a quick reminder about what we’re actually trying to fix, since I have never (ever!) actually heard this communicated clearly in policy, economic or mainstream discussions!

I want to return to the most important idea from Part I, the one that underpins every economic model humans have ever invented:

Every political economy has two moving parts: a coordination mechanism and a distribution mechanism.

Coordination is the part of the system that decides how prices get formed:

the signals that tell the economy what to build, where to send resources, which sectors should grow, and which should quietly wither in the corner.

Distribution is everything that comes afterwards:

who gets wages, who gets wealth, who carries risk, who gets upside, and who gets rescued when things go sideways.

And here’s the part policymakers have somehow missed for fifteen years:

Distribution is downstream of coordination.

If the coordination engine is broken, distribution will always be broken.

You cannot fix who benefits from the economy when the part that decides what the economy does has been dead since 2008. It’s like arguing about how to divide a cake that hasn’t been baked in sixteen years.

But that’s exactly what the post-2008 policy playbook has done.

Instead of repairing the coordination mechanism, the system that creates prices, incentives, and signals, everyone rushed to fiddle with distribution. We got tax credits to calm frustration, subsidies poured through the same clogged pipes, uplifting speeches about the “dignity of work,” mission-flavoured slogans about “building again,” and student-loan pauses that solved nothing.

We, taxpayers, also got enormous industrial bills that, somehow, always benefited the same corporate incumbents, plus a wave of techno-optimists insisting that “abundance” was a moral and mindset issue.

Every one of these efforts tried to treat inequality, wage stagnation, or unaffordability without touching the mechanism that produces those outcomes in the first place.

This is why nothing worked, and why everything actually got worse. Because distribution cannot be fixed until coordination is repaired.

And in this entire mess, only one major political figure actually intuited which half of the system was failing. (Prepare yourself….)

Trump.

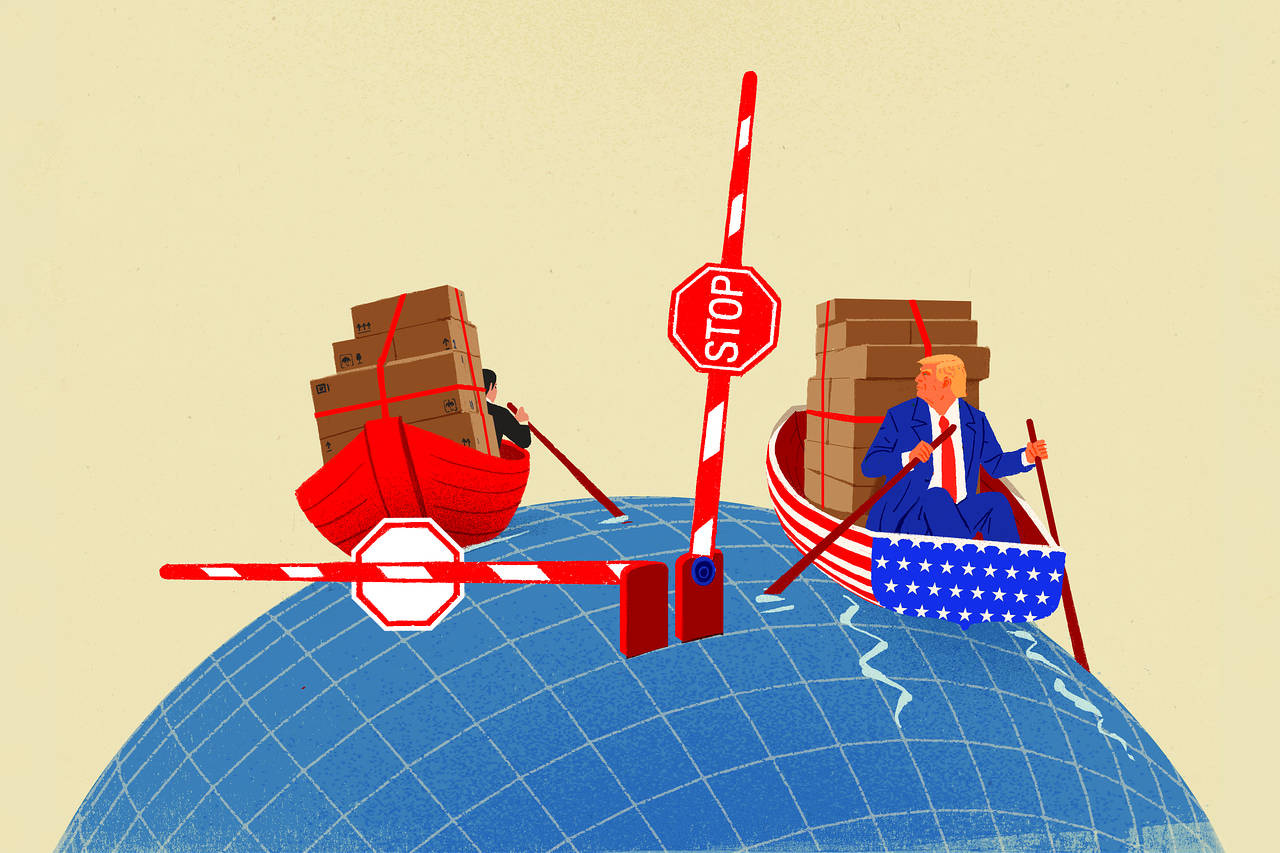

Say what you want about him (and sure, there’s plenty to say) but he does understand, instinctively if not intellectually, that if you want to change who wins and loses, you must seize the coordinator. And he is: tariffs, exemptions, penalties, approvals, sanctions, supply-chain choke points. He is pulling every lever available.

But while he is right about what matters, he was catastrophically wrong about how.

Instead of rebuilding institutions, he has become the institution. He personalized the coordinator, politicized it, and wielded it erratically by rewarding allies, punishing enemies, and injecting volatility into an already fragile system. He is closer to the real fault line than anyone else, and still manages to produce chaos instead of coherence.

Which brings us to the central question of this piece:

If coordination determines distribution, and if both neoliberalism and neo-mercantilist improvisation have failed, what does a functional alternative actually look like?

And how do we build one?

The Goal Is Not to Replace Capitalism

Here is the first thing I need to say with total clarity:

The goal is not to abolish capitalism. The goal is to rebuild the part of capitalism that tells the economy what to do!

We’re not resurrecting mid-century central planning or nationalizing your local grocery shops (hi Mamdani!). Nor do we intend to indulge in nostalgic protectionism or importing Silicon Valley’s techno-utopian aesthetic into governance.

The project is far simpler and far more ambitious:

Rebuild the coordination mechanism.

Because capitalism, despite its current state of exhaustion, still has strengths more extraordinary than any other form of economic model that we’ve seen throughout history. It can process unbelievable amounts of information through prices. It allows decentralized experimentation and rapid adaptation. It can translate millions of tiny decisions into a coherent, macro-scale pattern.

None of that needs to be dismantled. But it does need to be rescued. And it cannot be rescued while the coordinating engine remains broken.

So the real debate is not “state vs market.” That binary is dead, or a red herring at best.

Every modern economy blends both, whether it admits it or not. Neoliberalism pretended markets could coordinate everything; Trumpian neo-mercantilism pretends that politicians can coordinate everything. Both fail for the same fundamental reason:

They ignore the architecture underneath: the institutions, rules, constraints, standards, and feedback loops that make coordination possible in the first place.

What we need instead is an economic operating system built for the world we actually inhabit. Which is a world defined by complexity, interdependence, scarcity, speed, risk, and constant shocks.

In other words, we need a new model in which:

Capitalism’s intelligence is preserved;

the state’s purpose does more than appear in press releases;

and neither markets nor individual politicians can casually derail the entire system.

The task now is to build an economic model that matches the complexity of the century we’re living in.

What a Functional Coordination Mechanism Must Do

If we’re serious about rebuilding coordination, we have to talk about what coordination actually means. Economists often describe it as “the efficient allocation of resources,” which sounds tidy until you remember that our resource allocation system currently depends on meme stocks, implicit bailouts, and whatever interest rate the Fed chair fever-dreams up.

Philosophically, coordination is the answer to the oldest economic question:

How do we make collective decisions without a central brain?

Markets answered: through prices.

→ Pure neoliberalism

States answered: through planning.

→ Pure socialism

Trump answered: through whatever I Truth Social at 2:14am.

→ Pure Neo-mercantilism

In other words, it’s not any of the models that assume coordination happens either through pure prices, pure planning, or pure presidential improvisation.

Trump’s Neo-Mercantilism

Instead, imagine something more architectural. A system where the state shapes the terrain (the rules, standards, constraints, interfaces, eligibility criteria) and then steps back to let firms, investors, and innovators operate inside that designed environment. The state sets the structure; the market generates the activity. Coordination comes not from micromanagement and not from feel-good slogans, but from design.

This idea sits at the crossroads of several intellectual traditions.

Hayek argued that markets coordinate better than planners because they process information through prices. This is true, when price signals are coherent. But Hayek lived in a world before globalized finance and central-bank addiction to free money. Today’s prices often reflect the cost of money, not the cost of reality, which makes them about as informative as a dial-up modem submerged in a bathtub of liquidity.

On the other side, the developmental-state theorists like Chalmers Johnson, Alice Amsden, Robert Wade, who showed that state-led coordination can work spectacularly well when a country has strong institutions and a sense of national purpose.

But those models thrived under conditions that are hard to reproduce now: cohesive bureaucracies, social alignment, and the geopolitical wiggle room to protect infant industries.

So let’s crystalize this concept into what I’m calling the Architect State.

Our new Architect State must take a different path. It should say:

Markets coordinate well when the architecture beneath them is sound.

States coordinate well when they set rules rather than pick winners.

Which brings us to the work this new coordination mechanism must actually perform.

A functional coordination mechanism has to do six things:

It must process information better than the post-2008 liquidity machine.

Prices need to carry real signals again, otherwise we’re just choreographing investment around current hallucinations.It cannot rely on a single decision-maker.

As Hannah Arendt reminded us, institutions, not individuals, make freedom (and coordination) possible. Charisma is not a policy framework. I’m looking at you, Trump…It has to operate inside physical limits.

“Abundance” doesn’t magic new grids, minerals, labour, or compute into existence. Any serious model has to honour the reality of bounded resources.It must embed reciprocity.

This is structural, not moral. Without mutual obligation, legitimacy erodes. And Karl Polanyi warned what happens when markets detach from society: they tear themselves apart.It must be anti-fragile, not merely resilient.

In Taleb’s terms, a modern economy shouldn’t just withstand shocks, it should use them, learning and strengthening the way biological systems do. (Instead, right now, the system passes out at the whisper of the words “rate hike.”)It has to support innovation without turning it into systemic instability.

Schumpeter’s creative destruction works only when destruction doesn’t require trillion-dollar bailouts! Experimentation needs guardrails.

Put all of this together and you get one clear conclusion:

A modern coordination mechanism must be smarter than markets on their own, safer than the state on its own, and far more disciplined than anything we’ve built since 2008.

And everything that follows depends on accepting that.

The Three Levers of Coordination

If coordination is the problem, these are the mechanisms that actually rebuild it. They are boring, yes, but utterly necessary. They’re the difference between an economy that merely announces ambitions and one that can actually deliver them.

1. Institutional Design (the machinery)

A modern economy doesn’t run on vibes; it runs on institutions. Real ones. The kind that translate ambition into action. Without them, every “mission” or “moonshot” is just another glossy PDF.

To rebuild coordination, we need institutions that set the structure of the game:

Interoperability standards so energy grids, railways, data systems, and emerging tech can actually talk to one another.

Grid and compute oversight bodies that plan capacity the way central banks plan liquidity.

Planning offices that map bottlenecks, model constraints, and align incentives.

Supply chain councils that understand where things come from and what happens when they don’t.

Permitting reform authorities capable of approving projects in months, not geologic epochs.

National data and identity infrastructure, which is the boring, essential rails on which modern coordination runs.

This is the plumbing the mission-economy crowd never built. (But without it, nothing else works of course).

2. Reciprocal Risk (that pesky backstop!!)

After 2008, “they” quietly created a world where the biggest firms enjoy an implicit public safety net but owe almost nothing in return. That arrangement isn’t just unfair; as we have seen it completely destroys legitimacy and rots our society.

If public resources, guarantees, or protections are on the table, reciprocity has to be part of the arrangement,,, but not in the Mazzucato sense! I’m not arguing that the government should own equity in companies or claim a slice of their upside like a venture investor. The state is not a co-founder, and it shouldn’t behave like one.

Reciprocity here is structural, not financial. It’s about the obligations that keep a system legitimate and functional. If the public underwrites risk or provides protection, firms owe something back: not shares, not “state returns,” but behaviours that strengthen the architecture we all rely on:

Open-source contributions or shared IP when public money underwrites early risk

Domestic reinvestment so gains don’t disappear into buybacks

Resilience obligations: inventory buffers, redundancy, cyber requirements

Transparent disclosures so the public isn’t underwriting blind

Workforce standards tied to subsidies and contracts

Anti-capture guardrails so the same five incumbents don’t win everything

This is reciprocity as governance, not as ownership. It’s about ensuring public support strengthens the system rather than inflating private balance sheets. And this, unfortunately, is what Bidenomics never touch, and the Mission Economy got wrong.

J-Powell, central banker extraordinaire, with his money printer.

3. Resilience Metrics (the scoreboard)

We’ve all heard this before, but it’s true: what we measure determines what we build. For decades, our macro scoreboard has been GDP, inflation, and unemployment. A dashboard designed for the mid-20th century.

And yes, there have been attempts to “reimagine” this. The most famous, of course, was Jacinda Ardern’s decision to replace New Zealand’s GDP indicators with that subjective happiness index (?!). A move that was not only methodologically dubious (lol) but also rather conveniently timed to coincide with the part where GDP was shrinking under her leadership (double lol). That was not a bold new model of economic measurement. That was… something else.

This is not that.

A modern coordination system needs a very different set of metrics. Ones that actually capture continuity, stability, and shock absorption. Metrics that tell us whether the system can withstand volatility without collapsing into a heap of emergency bailout facilities and late-night central-bank interventions. Metrics that reflect whether the fundamentals, not the fantasies, are doing the heavy lifting.

We should measure:

Energy uptime: how reliably the grid stays on under stress

Supply-chain recoverability: how quickly systems reroute after a disruption

Credit stability: the brittleness or concentration of financial risk

Compute redundancy: whether AI and data infrastructure can fail gracefully

Time-to-recovery after shocks: the true measure of system strength

So yes, what gets measured gets built. But the point isn’t to throw GDP in the trash, it’s to recognize that GDP without context can be deeply misleading.

We don’t just want “more GDP”; we want a specific kind of GDP: the kind that comes from productive investment, durable capacity, real innovation, and long-term system strength. And without measuring resilience, continuity, and recoverability, we have no idea whether the growth we’re generating is stable and constructive… or brittle, debt-fuelled, and one bad shock away from collapse.

In other words: until we build a scoreboard that distinguishes healthy GDP from fragile GDP, we’ll keep mistaking volatility for vitality.

A Note On Detoxing the Economy From Free Money

But all of the levers I’ve just mentioned run into one final obstacle, the silent saboteur of every economic reform since 2008: our addiction to free money.

Here’s the thing: you don’t need to overthrow capitalism to fix the economy. You just need to end the era of permanent rescue and our chronic addiction to zero rates, quantitative easing and “temporary” interventions that somehow never actually retire.

A functional economy treats monetary tools like emergency medicine: you use them sparingly, precisely, and only when necessary.

An addicted economy, on the other hand, uses them constantly, prophylactically, and eventually reflexively.

Right now, we live in the second one.

The problem isn’t that the central bank stepped in during crises, it’s that the interventions became the default operating environment. Markets stopped learning, risk stopped being priced, and the financial system forgot how to function without a safety harness. In systems theory, this is called over-stabilization: the point when protection erodes the system’s ability to adapt, respond, or even sense reality.

Detox, in this context, means putting real, enforceable boundaries around intervention:

Rule-bound crisis tools with predefined triggers and actual sunset clauses

Time-boxed support that rolls off automatically, not when someone “feels comfortable”

Countercyclical buffers built up during expansions and spent during contractions

Macro-prudential rules with teeth that choke off dangerous leverage before it metastasizes

Clear separation between liquidity support and solvency support: the former keeps the liquidity pipes flowing, the latter distorts markets

Ending the use of monetary policy as shadow fiscal policy: If the state wants to redistribute resources, it should use the budget, not the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.

The principle is simple:

Never again should the U.S. economy require a central-bank drip just to exist!

And until we build a coordination mechanism that makes that possible, everything else is just stabilizing the patient while pretending to treat the disease.

The Coordination Problem: Solved?

So let’s bring this full circle.

Now that we’ve rebuilt the wiring and mapped the architecture for a new coordination (not distribution!) mechanism, we can finally circle back to the four traps from Part I, the traps that every post-2008 policy has fallen into, and the traps that have defined the last fifteen years of economic dysfunction.

Our new Architect State is designed to break each of them:

ONE: The Liquidity Reflex Trap.

This is the instinctive “when in doubt, print money” response. The reflex that turned the central bank into the economy’s permanent babysitter. The Architect State ends this by building institutional resilience and most importantly: restoring meaningful price signals!! When the system has buffers, standards, and clean failure modes, you don’t need trillion-dollar interventions every time a market wobbles. Liquidity becomes emergency medicine, not a lifestyle.

TWO: The Incumbent Capture Trap.

This is the trap where every new idea, subsidy, policy, or “national priority” ends up funneled through the same handful of corporate incumbents, because the underlying eligibility criteria hasn’t changed since 1993. With performance-based procurement, open standards, and real entry pathways, incumbents lose their automatic advantage, and monopolisation becomes a less prominent structural dynamic. Public money stops reinforcing existing hierarchies and starts building new capacity. The capture loop breaks.

THREE: The Direction-Without-Design Trap.

This is the trap where we announce missions, moonshots, climate goals, re-shoring plans, “build!” agendas, and industrial strategies, all without building the plumbing that makes any of those things possible. Without standards, permitting, data infrastructure, grid reform, or supply-chain coordination, every national ambition explodes on contact with reality. The Architect State fixes this by doing the boring work first: creating the institutional substrate that purpose can actually travel through.

FOUR: The Moralized Storytelling Trap.

This is the trap where rhetoric substitutes for mechanisms, and where we talk about fairness, dignity, resilience, abundance, or rebuilding, but never change the underlying wiring that shapes outcomes. Storytelling isn’t coordination. The Architect State returns us to actual machinery: institutions, rules, constraints, incentives. It makes purpose operational instead of performative.

Put all of this together and one thing becomes unmistakably clear:

A 21st-century economy doesn’t need a bigger state or a smaller state. It needs a state capable of architecting the terrain on which markets operate.

What This Looks Like in Practice

Ok I wanna stop being theoretical and become a little more concrete. Once you treat coordination as an architectural problem, you can actually design it; and when you design it, the practical implications become obvious.

HOUSING CASE STUDY:

Under an Architect State, zoning would adjust automatically when demand rises instead of requiring years of political trench warfare. Designs that meet safety and energy standards would be pre-approved rather than reinvented with every application. Public land would be released strategically through land banks, and modular construction standards would let builders scale without navigating bespoke regulatory labyrinths.

The result is obvious: housing gets built quickly, in volume, and without the ritualised political combat that currently defines the sector.

But it’s equally important to be honest about who loses under this approach, and what the second-order impacts actually are.

The first group of losers: are existing homeowners in expensive cities who have spent the last decade treating their houses as speculative assets. Faster building means slower price appreciation of course, and in some markets, actual price correction. A system designed for housing supply at scale is good for renters and new buyers, but it ends the era of using your house as a government-guaranteed retirement plan. Womp womp womp.

The second group of losers: are the NIMBY coalitions and neighborhood associations whose political power depends on scarcity. When zoning becomes elastic rather than discretionary, the ability to block projects evaporates. Their leverage shrinks because the rules, not their objections, determine what gets built. But… fuck these people.

The third group of losers: are the incumbents in the construction and permitting ecosystem who profit from complexity. When standards are modular and approvals pre-validated, the advantage held by firms that specialise in navigating bureaucratic nightmares disappears. Simpler rules introduce actual competition. Similarly to above: fuck these people.

Now to the second-order effects:

Land values flatten. The “location premium” driven by artificial scarcity starts to unwind. This doesn’t collapse wealth; it redistributes it away from passive owners and toward people who actually build things.

Political incentives shift. When housing supply expands automatically, politicians can no longer blame “the market” or “the planning system.” Accountability becomes clearer.

Labour markets become more flexible. If people can afford to move, they do. That’s good for productivity, mobility, and regional dynamism.

Local inequality falls. High-cost cities become accessible again, and the economic benefits of those cities decentralise.

Speculation becomes less attractive. Housing becomes a place to live rather than a financial instrument. That’s socially stabilising but financially uncomfortable for investors who’ve lived off leverage.

So yes, an Architect State approach can “fix” housing. But more importantly, it also rebalances power away from those who benefit from scarcity and toward those who benefit from production.

In other words: it rewards people who build, and disempowers people whose model depends on blocking.

This, I suspect, is what much of Bidenomics tried to do, albeit unsuccessfully for the aforementioned reasons.

AI AND TECH CASE STUDY:

This is the part of the economy where people get very jumpy whenever you mention rules, because the immediate fear is: if we slow down, China wins. So let’s sit with that for a second.

Under an Architect State, you’d still have compute registries, certified safety pipelines, interoperability rules, and public testbeds. But the point of these isn’t to wrap AI in cotton wool; it’s to stop the United States from sabotaging itself in the name of “speed.”

Right now, “move fast and break things” sounds great until you remember that some of the “things” we break are: financial stability, critical infrastructure, political systems, and basic trust in information. In a geopolitical competition, those are not things you want to casually put on the line.

An Architect State approach to AI starts from a very simple national-security premise: you do not win a long-term strategic contest by building brittle, opaque, failure-prone systems that you can’t even see into.

You win by building systems that are reliable, understandable, resilient under stress and interoperable across allies and sectors.

That’s what compute registries, safety pipelines, and interoperability rules are actually about.

Compute registries are not a European-style paperwork fetish; they’re a way of making sure you know where critical capabilities sit, how concentrated they are, and who controls them — which really matters if you think about wartime targeting, supply disruption, or export controls.

Safety pipelines are not there to “slow the game down”; they are there to force labs to demonstrate that they understand their own systems before deploying them at scale. In a world where models can be dual-use by default, that is not regulatory fussiness; it is basic risk management.

Likewise, interoperability and open interface rules are not anti-competitive, they are how you stop one or two firms from becoming single points of failure for whole sectors. If the United States wants AI embedded across its economy and its alliances, it needs systems that plug together, not a handful of proprietary fortresses.

Public testbeds are not about nationalizing AI; they are about creating a shared infrastructure where smaller firms, academics, and allied partners can experiment and innovate without being permanently dependent on the goodwill of three cloud providers.

So, who loses under this regime?

Primarily:

The frontier labs and hyperscalers whose power rests on opacity and lock-in,

investors whose thesis depends on “we move so fast nobody understands what we’re doing”, a la the Venture Mercantilists I have already described.

and any actor (public or private) whose influence comes from owning an opaque, unaccountable chokepoint.

And what are the second-order effects?

Firstly, you don’t slow innovation; you change its composition. Less energy goes into racing to release the biggest, least-understood model; more goes into robustness, integration, tooling, and real-world deployment. Similarly, less energy goes into constructing moats out of secrecy; more goes into competing on actual performance and usefulness.

On the China question: the uncomfortable truth is that the United States is not going to win by out-accelerating everyone on raw scale alone. We’re already seeing this. China will always have advantages in centralised control, data mass, and sheer bureaucratic stamina.

Where the U.S. (and its allies) win is on: quality of institutions, trust in systems, alliance integration and the ability to combine innovation with legitimacy!

An AI ecosystem that routinely blows up (hello incoming AI bust), corrodes public trust, or requires constant emergency intervention is not a strategic asset. This is, in fact, a vulnerability.

So the Architect State’s approach to AI isn’t “let’s slow down to be safe.” It’s:

Let’s design the environment so that going fast doesn’t mean driving blind.

This is how you build an advantage you can actually sustain.

A few other thoughts:

ENERGY. A functioning coordination framework would establish clear interconnection standards, ensure grid interoperability across regions, procure long-duration storage in a predictable way, and set carbon floor prices that adjust with conditions instead of swinging with elections. The outcome is a stable, investment-ready clean-energy system instead of the current patchwork of bottlenecks and uncertainties.

DEFENSE. Capability-based procurement, modular standards across services, competitive prototyping, and open interface architectures would accelerate modernization and increase competition. Instead of a system captured by a small set of incumbents, you get a structure where performance actually determines who wins.

FINANCE. The changes are even more structural: countercyclical buffers built during expansions, automated bankruptcy pathways that prevent contagion, real-time collateral registries, and rules that clearly distinguish liquidity shocks from solvency crises. A financial system built on these foundations can absorb failures without triggering systemic collapse.

Put differently: when coordination is treated as a design problem instead of an ideological battleground, the economy finally starts doing what it’s supposed to do.

Why This Works

Let’s step back. The core insight of this entire model is that coordination isn’t about control or chaos, it’s about information.

A functioning economy is one that can interpret signals, respond to constraints, and allocate resources with some grounding in reality.

Neoliberalism assumed markets could do this through prices. Trumpism assumes a president could do it through personal decree.

The Architect State, however, argues that only institutions: rules, standards, constraints, and durable structures, can process information at the scale and complexity a modern economy requires.

That’s why this approach would work. It handles complexity without smothering innovation; it preserves legitimacy without drifting into technocratic paternalism; and it constrains risk without killing dynamism.

And that brings us to the real choice in front of us.

For fifteen years we’ve lurched between liquidity addiction, presidential improvisation, corporate capture, and distribution theatre. We’ve seen multiple cycles that stabilise nothing and fix even less.

The alternative? Is simply to rebuild the mechanism that tells the economy what to do: the part that restores real price signals, forces incumbents to compete, makes missions executable, and grounds public ambitions in actual institutional capacity.

In that world, the economy doesn’t depend on permanent rescue. It doesn’t collapse at the first sign of volatility. It doesn’t hand the future to incumbents by default or require the Federal Reserve to use its invisible hand. It becomes a system that behaves predictably enough to build on, and resiliently enough to trust.

I suppose we already know what broke, and we now know what’s missing. The real question is whether we want to keep propping up a failing model with liquidity and slogans, or whether we want to design something that actually functions?

Because once you see the economy as something we build, not something we inherit, the path becomes unmistakably clear:

Fix the coordinator, and everything downstream has a chance to work again.

And here’s the part nobody seems to grasp: once coordination is rebuilt, we can finally choose whatever distribution mechanisms we want… and they will actually work! You want larger safety nets? Fine. You want wage supports? Fine. You want regional investment, industrial revival, childcare credits, or ambitious public missions? Great. Once the coordinator is functioning, distribution stops leaking out the bottom of the system and starts doing what it’s meant to do.

Repair the architecture, and the economy becomes something we can steer again, not something we’re forever trying to catch as it falls apart.

"Where the U.S. (and its allies) win is on: quality of institutions, trust in systems, alliance integration and the ability to combine innovation with legitimacy!"

Strange. I would have thought if U.S. and it's allies were winning on quality of institutions, were earning superior trust in their systems, and were seen to be more legitimate by the world at large, this article wouldn't have been necessary in the first place? Hasn't the author seriously underestimated the challenge?

Very Interesting, a lot of ideas to absorb and understand. Are you doing anything to move these ideas further toward action? Do you plan to publish a book? Maybe a good set of podcasts explaining ideas and having guests to discuss? Would love to see a proposal on reforming a government agency around these ideas.

I fed part of the document to Google's AI & asked it to build an infographic. Did a nice job using a car engine analogy, I'd be glad to share it for what it's worth if you have a place for me to put the file (.png)

Thanks for the work.