Is AI the New Shadow Bank? (Yes...)

Why the real innovation isn’t artificial intelligence but artificial liquidity.

The Credit Revolution

In 2022, I had dinner in Paris with a group of bankers, right across from the Eiffel Tower. We were there to talk capex financing for industrials. Too much food, too much wine, too much fun.

There are rarely many women at these tables, so I was delighted to have one sitting opposite me. Her name was Hayley. As the night went on, the conversation drifted from balance sheets to philosophy.

“Have you considered,” I asked, “that the off-balance-sheet financing in this sector could become problematic? And have you read Zoltan Poszar on this? He’s fabulous.”

I grew to learn of and understand Poszar’s work for the simple reason that my first job out of college was, rather unfortunately, on Wall Street in NYC, working on the Mortgage-Backed Securities trading floor at a large institutional trading bank at the height of Occupy Wall Street.

(My next job was even worse: untangling n-dimensional collatoral against billions of dollars of commercial mortgages. It was a baptism of fire, that’s for sure.)

Poszar is controversial: part monetary genius, part macro heretic. But I’ve always loved his work, especially on new currencies and what he calls “monetary realism.” His most famous paper, Shadow Banking (New York Fed, 2010), was a Rosetta Stone for the financial crisis: it mapped the hidden plumbing of global credit creation, the vast web of repo markets and money funds that had quietly replaced traditional banks as the real engine of liquidity.

The woman looked at me kindly and said, “Yes, I’ve heard of Zoltan. I co-authored Shadow Banking.”

The woman in front of me was Hayley Boesky. I was mortified.

Anyway, I’ve been thinking about Boesky and Poszar a lot recently because, fifteen years later, we’re living through another off-balance-sheet boom. Everyone calls it the “intelligence revolution.”

They’re wrong. It isn’t about intelligence. It’s about credit.

What Poszar Saw

Zoltan Poszar’s genius was to see that money isn’t just what central banks create, but rather whatever the financial system treats as safe, liquid, and pledgeable.

He showed that there were two banking systems:

One visible, with branches and regulators and deposit insurance.

The other, invisible: a shadow system made up of repo markets, money-market funds, prime brokers, and off-balance-sheet vehicles, where credit was created and destroyed in real time, far from the reach of oversight.

In that shadow world, “cash” wasn’t currency. It was collateral: Treasury bills, mortgage-backed securities, anything that could be pledged overnight for funding.

By 2008, this shadow banking system had become so vast, so entangled, that when confidence cracked and repo markets froze, the entire global economy stopped breathing.

People say that nobody could predict the 2008 crisis. This is fundamentally not true; lots of people could feel the markets starting to lose control.

Rather, what they mean when they say that nobody could predict 2008, is that nobody could see the problem arising in the fundamentals that were being used as yardsticks.

Why?

Because the problems were showing up in different systems. In newly created shadow systems.

It wasn’t subprime homeowners who broke the system; it was the silent plumbing that connected everyone else. The liquidity pipelines nobody had bothered to map until Poszar and Boesky and their other co-authors did.

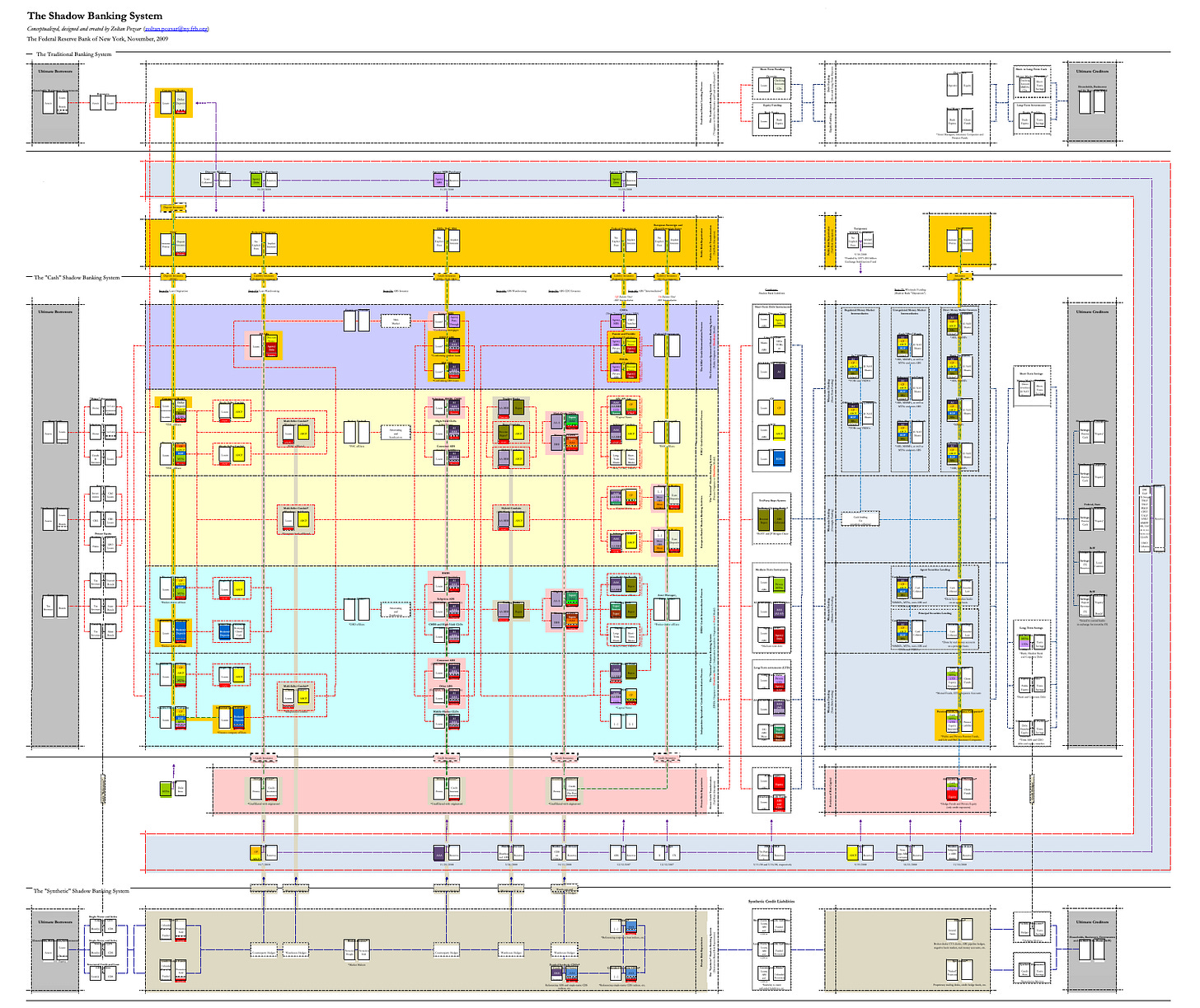

Their diagrams looked like something out of a conspiracy thriller: a web of arrows looping from hedge funds to broker-dealers to money-market funds to the Fed, all moving faster than any regulator could track. But beneath the chaos was one elegant, horrifying insight:

Collateral had become the new form of money.

The Shadow Banking system, in a diagram (Poszar, 2010)

And once you see the world that way; once you understand that modern finance is just a system of promises backed by whatever everyone agrees is safe enough to lend against, you can never unsee it.

Which is why, when I look at the current AI frenzy, I don’t see neural networks or generative models or the “dawn of artificial consciousness.”

I see a new collateral class.

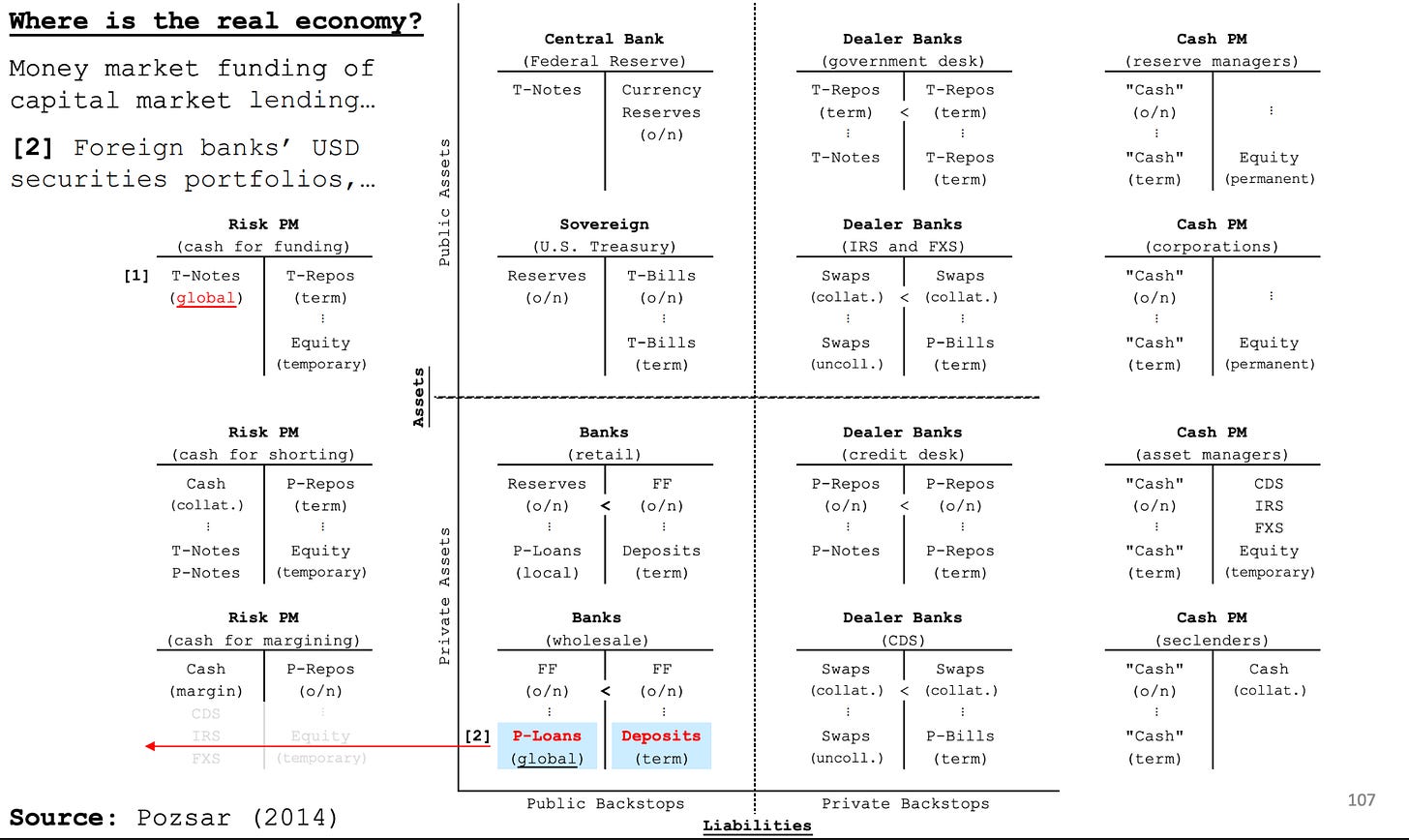

This diagram looks similar to the Shadow Bank diagram, no?

Because fifteen years after the housing bubble burst, the same structure is quietly re-emerging. Only this time, the collateral isn’t mortgage pools.

It’s GPUs, compute contracts, and model access rights.

The Financialization of AI

Nvidia doesn’t just sell chips, in the same way that Tesla doesn’t just sell cars, and SpaceX doesn’t just sell rockets.

It sells the dream of infinite demand. In much the same way Goldman once sold the dream of infinite homeownership.

The buyers this time around are no longer mortgage originators in Florida called Nathan and Chip; they’re compute resellers with names that sound, oddly, like heavy metal bands: CoreWeave, Lambda Labs, Crusoe.

Anyway, these heavy rockers (CoreWeave, Lambda Labs, Crusoe) don’t pay cash for their GPUs upfront. I mean, why would they? When credit is cheaper than capital, cash is for suckers.

(Yes- let’s sit with this single, throwaway line for a moment which could be a post of its own: debt is expensive at the moment, so how the hell is debt cheaper than capital, I hear you asking? Oh, that’s right… because all of these companies have been financed in the Most. Expensive. Way. Ever. Using… venture capital!)

So no, of course they don’t pay cash upfront. Instead, Nvidia extends vendor financing. Which is basically the financial equivalent of, “Chill, just pay me later.” And sometimes this is structured as leases. Sometimes as deferred payments. Sometimes as equity stakes (that look suspiciously like collateralized debt.)

Then the cycle begins.

How exactly does it work? Well, I suspect just like this:

CoreWeave takes the GPUs and leases them out again: to OpenAI, Anthropic, Stability, xAI, each of whom are, in turn, financing their compute bills with borrowed money from the very companies selling them the hardware.

The simplified version of Shadow Banking For Dummies

It’s a daisy chain of both debt and destiny:

Microsoft lends to OpenAI so OpenAI can rent GPUs from CoreWeave so CoreWeave can pay back Nvidia so Nvidia’s stock price can keep justifying Microsoft’s investment in OpenAI.

Somewhere in that circle, a sovereign wealth fund in Abu Dhabi nods solemnly on a stage at a large investment conference, calling it “the future of productivity.”

The whole thing runs on recursive belief: credit funding compute that generates hype that raises valuations that enable more credit to fund more compute.

If you don’t know what the fuck I’m talking about at this point, then that is exactly the point.

And if you speak to bankers in 2008, this is exactly how they felt, too!

Because you eventually stop being able to tell whether this is industrial strategy or performance art, and as someone who has seen a LOT of bad performing art, trust me when I say that this is closer to the latter than the former.

In this system, and going back to finance, each player treats the same stack of GPUs as both asset and currency: something to be borrowed against, resold, or re-pledged.

Hardware becomes collateral → Collateral becomes liquidity → Liquidity fuels more hardware sales.

It’s elegant, self-reinforcing, and delusional; and it’s the trinity of modern finance.

If you swap the nouns, the diagram is identical to 2008.

Replace “mortgage” with “GPU.”

Replace “CDO” with “compute lease.”

Replace “repo” with “vendor financing.”

Congratulations! You’ve rebuilt the shadow banking system, this time in silicon form.

The Illusion of Infinite Liquidity

Every boom (or bubble?) rests on a shared hallucination: that its collateral is infinite, liquid, and blessed by the gods of endless demand.

In 2008, that collateral was houses. In 2025, we see now that it’s compute.

The assumption is the same; that someone, somewhere, will always need more of it. And that liquidity will never dry up. And that credit can keep expanding because the underlying asset can always be sold.

But unlike the ins-and-outs of the hardware being built, liquidity isn’t a law of physics; it’s a mood. And moods change. (I am heavily resisting using the word vibe here, although yes, we’re basically living in a vibeconomy).

So what happens if (when?) AI demand stalls? If model training costs outpace revenue, or if the market decides we have enough chatbots for now?

Then, simply:

The resale market for GPUs collapses

CoreWeave’s balance sheet evaporates.

Nvidia’s vendor loans turn into unpaid receivables.

And the same self-reinforcing loop that inflated the boom unwinds in reverse.

This is how all credit bubbles end: with a collective realization that yesterday’s collateral isn’t money anymore.

Zoltan once said that the shadow banking system is built on “secured funding.” But that phrase hides a small, terrible truth: secured against what?

When the collateral itself is in question, nothing is secured.

Or, as Hayley Boesky might have said to me at the Eiffel Tower, over Burgundy,

“When collateral is God, everything else is theology.”

The New Repo Market

Once upon a time on Wall Street, there was a thing called a repo, short for “repurchase agreement.”

Here’s how it worked:

You handed someone your Treasury bond for the night

They handed you cash

Both of you promised to reverse the trade in the morning.

It was the financial equivalent of a pawn shop for billionaires, “hold this until tomorrow, I just need some quick cash.”

You lent cash against government bonds, took a tiny spread, and prayed no one defaulted before breakfast. Simple, right? (Unless you’re into Argentinian bonds, like my But This Time It’s Different better half Alex!)

(If you’re interested, Poszar has an excellent albeit dizzying deck of 161 slides that look just like this, which aim to answer the question: Where is the real economy?)

So in this new AI economy, the same logic applies. Except the collateral isn’t government-backed paper anymore. It’s hardware: racks of GPUs buzzing in dark warehouses, drawing power and capital at the same time.

Instead of Treasuries, it’s racks of H100 GPUs sitting in windowless warehouses outside Reno and Las Vegas. The deals are structured the same way: short-term financing against long-term promises of revenue.

Call it the repo market of compute.

A lender fronts money for hardware; the borrower pledges the GPUs as collateral and repays the loan from future “training runs.” Then someone else takes that same compute capacity, securitizes it into “cloud credits,” and pledges it again.

By the time you trace a single rack of chips, it’s been pledged five times:

Nvidia → CoreWeave → OpenAI → Microsoft → Oracle → Nvidia again.

It’s the circle of (financial) life, except nobody’s quite sure who’s actually holding the hot potato when the music stops.

If Stephanie Kelton wanted a Circular Economy, she got one. Or at least, circular leverage. Hidden exposure. Maturity mismatch (when will we ever learn!!). The entire alphabet of shadow risk, but wrapped in a ChatGPT-created press release about “democratizing intelligence.”

There’s something almost poetic about these shenanigans: the very machines we built to forecast risk and model the future are being financed by the same fragile leverage that once brought the global economy to its knees; proof that they can learn from everything except the past.

The Nationalization of Speculation

So, here’s something to really think about. How is today different to 2008? In many ways, but…

In 2008, shadow banks operated in spite of the state: slippery, offshore, too fast for regulators to catch. (Also: the extent to which regulators were trying to catch this is debatable).

The United States is now both market-maker and guarantor of the AI boom. Washington subsidizes the chips through the CHIPS and Science Act (a $39 billion carve-out for semiconductor manufacturing and tax credits), the data centers through Department of Energy loans and power-grid incentives, and even the demand through Pentagon and DARPA AI contracts.

When the government isn’t funding the hardware, it’s buying the outputs.

Europe, never one to be left out of a subsidy party (!), is doing the same under the IPCEI framework and Horizon Europe, shoveling billions into what it calls “strategic autonomy.” The Commission has pledged more than €30 billion for AI-ready data centers, €1.2 billion for cloud and edge infrastructure, and another €7 billion for its EuroHPC supercomputing program, all while quietly underwriting the same private credit loops it claims to regulate.

And then there’s the Gulf.

The UAE’s MGX fund, backed by Mubadala and G42, is targeting $100 billion for AI infrastructure (a sovereign-wealth powered shadow bank in all but name).

Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) has earmarked $40 billion for AI projects, including massive GPU purchases and a 500-megawatt data center stocked with Nvidia hardware.

Even Qatar has joined in, funding AI hubs and regional cloud expansion as part of its Digital Agenda 2030.

From Washington to Brussels to Abu Dhabi, every government is now a co-signer on the AI balance sheet.

To be clear: this is not laissez-faire capitalism. It’s financialized industrial policy; a speculative arms race disguised as national strategy.

Each state is now effectively leveraging its balance sheet to sponsor collateral creation, hoping that enough national debt and datacenters can manifest “technological sovereignty.”

It’s Keynesianism (governments doing what they’ve always done in a slowdown: throwing money at whatever moves), only this time, it isn’t highways or shovels, it’s racks of GPUs.

And just like the repo markets of 2008, it all works perfectly until confidence falters and everyone realizes the collateral was just leverage in disguise.

Maybe This Is Totally Fine?

Alex, my BTTID other half, likes to remind me that not everyone sees a blood-splattered economy ahead.

Goldman Sachs (yes, the same institution that relies on sentiment being positive to realize its PnL), recently published a report titled Why We Are Not in a Bubble… Yet. Their argument is straightforward, and not entirely wrong.

Yes, there are echoes of the DotCom in 1999: soaring valuations, vendor financing, and a handful of dominant firms pulling the rest of the market up by its teeth.

But the difference, they say, is that this time the numbers add up.

Technology profits have risen fivefold since 2009, balance sheets are fortress-strong, and most of the spending boom is funded by free cash flow rather than debt. The “Magnificent Seven” aren’t speculative startups; they’re industrial behemoths with 25–40% profit margins and negative net leverage.

In Goldman’s framing, bubbles form when valuations detach so far from future cash flows that the math no longer matters.

By that metric, we’re stretched, sure, but still far from dot-com delirium.

This, they argue, isn’t tulip mania. It’s more like the railway boom of the 19th century: messy, capital-intensive, overbuilt, but ultimately transformative.

When the froth burns off, the rails remain.

Well… maybe.

But the question isn’t whether the infrastructure is real. It’s whether the revenues are.

Yes, the chips exist. The data centers exist. The power bills are very real. But the cash flows they’re meant to generate haven’t shown up yet.

As highlighted, and why this is more like 2008 than 1999, sector’s profits still largely come from within itself:

Microsoft funding OpenAI, OpenAI buying compute from CoreWeave, CoreWeave buying GPUs from Nvidia, Nvidia selling to Microsoft.

A perfect, recursive economy of belief.

For the system to sustain itself, AI needs to escape that loop and start paying for itself through productivity gains or entirely new industries. And that’s the real timing problem: the money is being spent now, while the benefits, if they arrive at all, may take years to materialize.

Can AI produce the kind of cash flows that justify trillion-dollar valuations without replacing entire industries? Or is “being a tool” not enough? How many human workstreams does it need to absorb before it becomes self-funding rather than self-referential?

The risk isn’t that AI is imaginary. It’s that it’s prematurely financialized; that we’ve capitalized the promise of transformation before the transformation itself.

So yes, the infrastructure may endure, as Goldman says. But the credit cycles that built it might not.

The imbalance is simple: the money has already been spent, but the earnings that justify it haven’t arrived.

Surviving the Coming Crunch

Every boom sounds invincible until someone checks the balance sheet.

If credit tightens, or if the returns on AI start to flatten, the illusion of infinite liquidity vanishes overnight. Nvidia’s vendor loans come due. CoreWeave and Lambda default on their leases. Hyperscalers quietly roll back their commitments.

The resale market for GPUs freezes, and suddenly the “compute economy” starts to look like the subprime unwind. Except this time, the collateral is whirring in a warehouse instead of rotting in Florida.

And when it cracks, there’s no Fed backstop for GPUs, no discount window for stranded hardware, no lender of last resort for the servers in Reno.

(Although I do want to write about the mechanisms that may exist for this type of a bailout, maybe in my next post, because not only will we likely see it coming to pass, but it is also a fun intellectual exercise in trying to actually understand the direction of liquidity in the monetary system right now!)

So if (when) liquidity evaporates, the financing chain seizes, and the data centers becomes a bonfire of sunk costs, capital burns faster than the economy can replace it.

And that’s the thing about bubbles: they always work until they don’t. And when they don’t, they unwind exactly the way they were built.

But the collapse isn’t the end. It never is. So let’s get philosophical about this.

Poszar once said that:

The financial system isn’t a structure; it’s a circulation: Credit flowing through pipes, transforming whatever it touches into collateral.

That insight still holds. Shadow banking didn’t die in 2008; it just changed shape. It moved from mortgage tranches to margin loans, from crypto tokens to (dare I say- private credit?!) to GPUs. Wherever there’s new collateral, a new shadow forms around it.

From mortgages to treasuries, from crypto to compute, every technological revolution invents its own liquidity illusion, and its own way of turning faith into funding into RoIs.

This one just happens to exist in a world where every other asset class has flatlined: bonds exhausted, property illiquid, venture tapped out, so all the shadow behavior has collapsed into a single trade: AI.

The plumbing Poszar mapped has simply found a new material to flow through: silicon instead of paper.

We’ve built an intelligence that can write sonnets, trade stocks, and pass the bar exam, but the real miracle isn’t the AI.

It’s that we’ve taught credit to dream again!

The Poszar framework mapping is absoltely brilliant. The maturity mismatch between capital deployment (now) and revenue realization (later?) is the key vulnerability everyone is ignoring. Your point about GPUs being pledged five times in the daisy chain is exactly what happened with CDOs - synthetic exposure built on synthetic exposure until nobody knows who owns what risk.

One of the key contributors to 2008 was the relative magnitudes involved. When there are $20 in bets for every $1 in underlying value, a 5% dip can wipe out the whole market, which makes even a hint of a downturn a valid reason to panic.

I love the connectivity diagrams you show, and I suspect estimations of the relative magnitudes would add the last piece of the puzzle -- exactly how unstable is the AI ecosystem today? What magnitude of correction would force the bubble to pop? (And how much could federal bailout funding do, at what cost, to postpone/exacerbate a hypothetical moment of truth?)

This may not be easily answerable, but I thought it was worth asking, in case anyone reading this has further understanding of the AI industry's financing details. I've not been successful in finding better numbers myself, and I suspect that many key details pertinent to understanding the _degree_ of leverage are buried in the confidential fine print of private contracts between the corporations involved.

Any thoughts?