Kazimir Malevich and the Art of Staying Sane in a World Gone Fucking Crazy

Why a 1915 painting of a black square might be the only guidebook we have for the chaos of AI, politics, and existential noise.

TL;DR: The world is too crazy to handle. Let’s all become Malevichian minimalists.

I was walking through Notting Hill on a recent evening walk when I stumbled upon a little book exchange store that was open late. I stopped to look in the window at an exhaustive encyclopedia set, containing multiple original volumes, when the hardback next to it caught my attention.

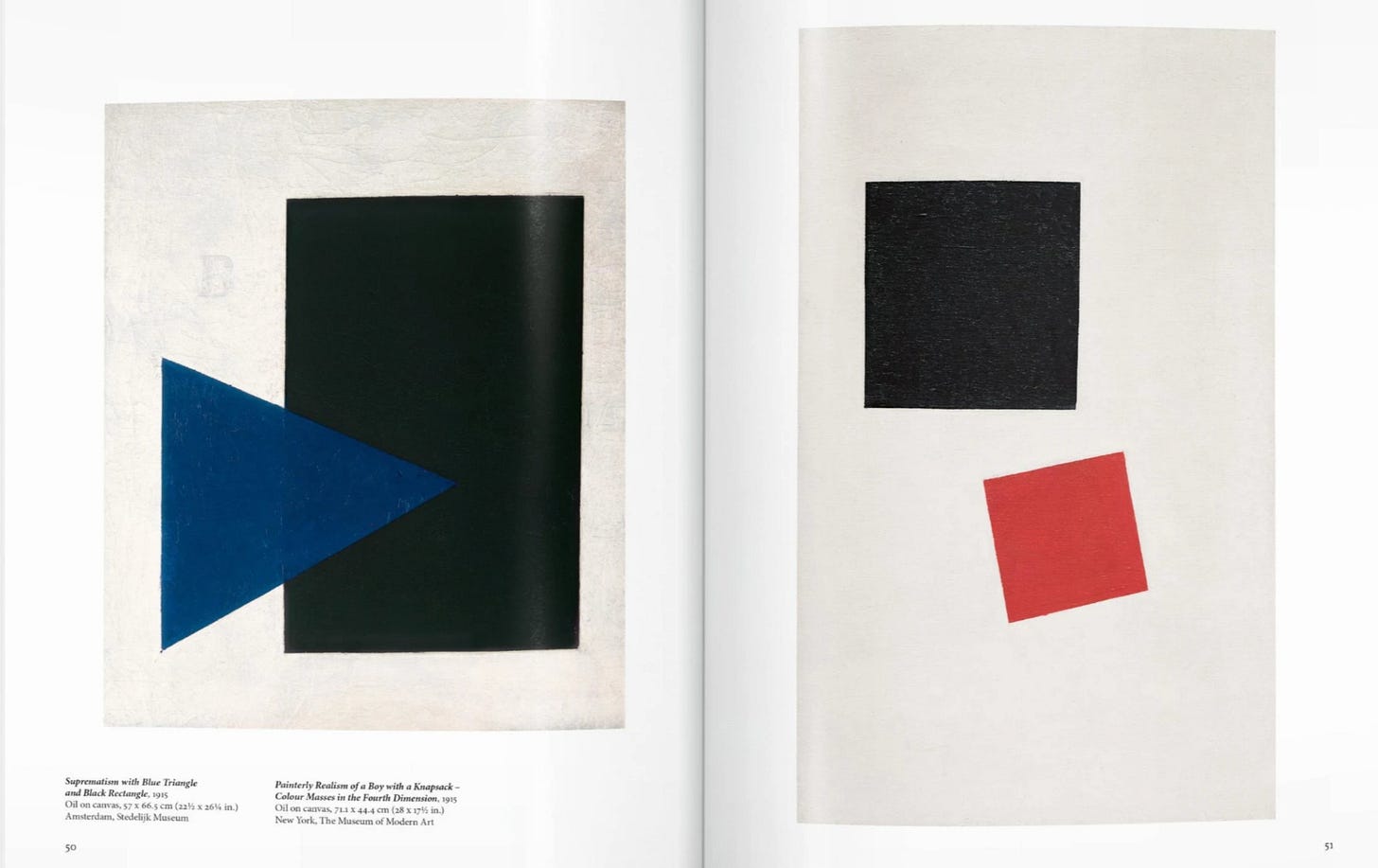

Large and white, depicting a collision of shapes that were taking themselves apart and reassembling mid-air. Blocks of colour flinging themselves across the store window, impossible to miss.

Ah! I couldn’t remember the last time I felt such short, sharp impromptu joy.

Kazimir Malevich! I have found you!

The Moment the Image Collapsed

They say that there are moments in art when a painting doesn’t just change how things look, but that it breaks the whole way of seeing wide open. The cynic in me isn’t entirely convinced, because life rarely shifts as suddenly or dramatically as it does in hindsight, and of course these large revolutions tend to look more obvious in retrospect than they ever feel in the moment.

In any case, Kazimir Malevich turned the art world upside down with his painting Black Square, shown in Petrograd in 1915.

In traditional Russian Orthodox homes, there is such a thing as a “beautiful corner”, also known as the red corner, where people hang their most sacred religious images (also called “icons”). Usually it is the face of Christ or the Virgin, positioned high in the room so prayer and attention naturally rise toward it. The icon becomes the spiritual centre of the household and the point from which orientation and blessing seem to emanate. Even in public art exhibitions, Russian viewers carried this instinct by designating the upper corner of a room as a position of sanctity where holiness was expected to reside.

So when Malevich unveiled the Black Square in 1915, he didn’t just hang a painting on a wall, he installed it in that exact sacred spot, treating a plain black square the way a (quite religious, remember!) Russian household would treat God.

People supposedly fell quiet when they saw it from the shock of realising that the whole order of images had been quietly overturned. The spot where the most sacred, meaningful picture was meant to hang was suddenly filled by… a black square that showed nothing at all.

Whether or not any of this is true, who knows. It does seem to sound rather over-intellectualized; after all, a painting is just a painting. A square is just a square. And most people (yes, even those who inhabit the upper tiers of the art intelligentsia) do not usually find themselves catapulted into grand theological reflections on the nature of love, meaning, and existence at the mere sight of a plain black-shaped painting.

Regardless. Whether it was a big deal in that moment, or whether the meaning settled in more slowly as critics, historians, and artists continued to interpret and reinterpret his work, Malevich and his square did in fact have a sizeable impact on the art world. In a deep structural sense

For centuries, the value of a painting (and thus the skill of the painter) was judged by how convincingly it could bridge the gap between what the eye sees and what the hand can render. Art was, in essence, a translation task: the world existed “out there,” and the artist’s job was to recreate it on canvas with as little loss as possible.

The central question within the canon of art remained:

How can paint more accurately capture the world as we experience it?

Malevich inverted that question entirely.

Instead of trying to represent the world, he asked whether painting could interrogate the very structure of seeing itself. It sounds like bullshit, sure, but bear with me.

Where earlier artists tried to close the gap between perception and depiction, he exposed the gap, to make it visible.

In that sense, the Black Square was not a refinement of the tradition but (and especially at the time) an incomprehensible escape from it. It announced, quite plainly, that the task of art was no longer to copy the visible but to consider what makes the visible possible in the first place.

In some ways, it is similar to the sudden arrival of generative AI today. Because until recently, we kind of thought of intelligence as being able to answer questions correctly. And yet, AI shows us that intelligence might also be about generating forms, not just interpreting them. For many people, it has shifted the very definition of what intelligence is, what “creating” means, and whether human perception is still the centre of the system.

Malevich’s square did exactly the same for art.

It didn’t just introduce new forms (although it certainly did that), it changed the definition of what art was for. Its purpose shifted from “accurately depicting reality” because there were no other technologies to do that, to “revealing the deeper structures that make reality appear at all.”

From practical to philosophical interpretations of life.

Of course, none of this kind of stuff ever happens in a vacuum. Other artists of the time were also pushing against realism. Picasso was breaking objects into shards, Kandinsky was moving toward pure abstraction, Virginia Woolf was dismantling and rewriting the Victorian novel from the inside out, and Schoenberg was undoing the rules of music.

But, if you speak to art historians, they will argue that Malevich went further than his contemporaries. While others stretched the old forms, he got rid of the forms entirely. He believed, almost coldly, that the world had changed too fast for art to keep pretending objects were stable or knowable. Perspective, narrative, solid things, coherent space? None of it matched the modern world anymore.

And it’s not like you could blame these artists for practically losing their minds!

Russia (and Europe, more broadly) was entering a period of profound upheaval. The First World War was killing millions while shattering every assumption about religious, political and economic stability, continuity, and order. Industrialisation had repossessed daily life at a speed no one was prepared for: factories replacing fields, machines replacing workers, trains and telegraphs shrinking distances, electricity altering the very concept of day and night! Cities were growing so quickly that they felt more like experiments than places.

This led philosophers, and artists more broadly, to question the very foundations of reality. Bergson challenged the nature of time. Freud exposed the terrifying unconscious, Husserl put forward that perception itself, thus humans, needed to be rethought from the ground up.

And there was no reprieve from this insanity in science either, which was just as chaotic: Einstein had just rewritten the structure of space and time, and matter itself was being cracked open by early atomic physics.

Politically, of course, the old world was disappearing. Literally. Monarchies were falling. Revolutions were kicking off. The present, never mind the future, looked unstable, accelerated, and decisively abstract.

Sound familiar? Indeed.

For Malevich, painting a dumb bowl of fruit or a landscape in 1915 felt dishonest, because the world itself was no longer arranged like that. What good was a piece of fruit, when society was inverting in on itself? Reality had become fragmented, unstable, accelerated, and the old image-world couldn’t keep up.

So the Black Square was meant as a reset. A clearing of the old visual language, apparently, so that something new could be built in its place.

Suprematism as a Philosophy of Perception

Suprematism is often described as pure abstraction, but in my opinion this is slightly misleading, because this definition suggests a stylistic preference rather than an ideological stance. Remember: Malevich had just turned art from a practical to an overwhelmingly philosophical endeavor.

He was no longer refining painting but redefining the conditions under which painting (read: perception) could occur.

The square, the line, the floating plane of color. These were not decorative geometries of old, but now he declared them the primitive units of a new perceptual grammar. He was seeking, in effect, the perceptual equivalent of what Husserl sought in consciousness: a reduction to the phenomena themselves, an encounter with the “things” before the world’s sedimented meanings attach to them.

It is not unlike what W. Brian Arthur, my favorite complexity scientist, would later argue about economics. That beneath all the apparent complexity there lies a language, or a set of elemental generative rules from which the entire system emerges.

Malevich was doing something similar for perception: stripping experience down to its smallest meaningful forms so that a new visual language that was capable of holding the fractured and disintegrating world of modernity could be built from the ground up.

In this sense, Malevich is closer to the thinkers of philosophical modernism than to most painters working with abstraction.

His project echoes the work of the French poet Stéphane Mallarmé, who believed that language itself had to be rebuilt from the ground up. Mallarmé felt that the old forms of writing were too weighed down by inherited meanings to express the modern world, so he stripped language back to a more essential state in order to create something new.

Suprematism, in this light, becomes a kind of visual phenomenology, and an attempt to get back to the basic conditions of how we see and make sense of things, especially when the old categories for understanding the world have stopped working.

When Malevich talks about “the supremacy of pure feeling,” he isn’t referring to emotion in the ordinary sense. He means a kind of sharpened perception or a way of seeing that isn’t filtered through familiar images or stories.

In Suprematist works, shapes don’t actually illustrate anything; they behave like events. They create a field of forces, tensions, and relationships where meaning comes from how the shapes exist together, not from what they represent. For example, a red square doesn’t stand for an object. It simply appears as a kind of pressure or presence, something that resists being translated into anything else.

Weird? Yup.

This is where Malevich differs from other abstract painters of his time. Mondrian’s grids still echo the structure of trees, landscapes, or the underlying order of nature. Kandinsky’s forms, for all their abstraction, are still connected to a spiritual, expressive idea of colour and line. Malevich wants something far more radical: a visual world completely detached from objects, references, and the visible world as we know it.

The Zero as Generative Ground

If Suprematism has a center, it is the idea of zero: the Black Square as the “zero of form,” the foundational point from which new perceptual worlds can be built. To call a work “zero” is not to describe emptiness but to name a beginning. Zero is an origin, the point at which inherited constraints fall away and new structures can be imagined without the inertia of the past.

Now, it’s absolutely worth remembering that the idea of “zero” has always been culturally disruptive. And terror inducing.

In mathematics, zero didn’t just emerge as a simple placeholder, although it feels like it must have always existed in the number line! The concept of zero actually represented a conceptual revolution, and it’s worth reading Seife’s “Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea” to really comprehend this.

In short, ancient Babylonian and Mayan systems moved closer to the form of a zero, but it wasn’t until Indian mathematicians formalised zero as both a number and an idea. A symbol for nothing and a position from which all calculation becomes possible. Henceforth, mathematics as we know it began to unfold. Zero allowed for negative numbers, algebra, calculus, and eventually the entire architecture of modern science. It didn’t denote emptiness, rather it literally opened the door to infinity.

Malevich was tapping into this same logic.

By calling the Black Square “the zero of form,” he was invoking a structure with deep mathematical precedent: the notion that if you reduce a system to its minimal state (to nothing) you create the conditions for an entirely new system to arise.

For Malevich (and importantly for nearly every representation of zero in art, math and otherwise!!), zero is never just an absence! It is the generative ground for everything that follows.

Malevich’s zero is not the nihilistic void but the fertile null from which his art can re-emerge unburdened.The square marks the moment when art stopped being about representing the world and started being about how we perceive it.

Illegibility and the Politics of Form

It is worth revisiting the political landscape through which the Black Square arrived, because the context matters. Malevich’s gesture was not floating around a neutral space of pure aesthetics. In fact, it emerged in a moment when Russia was turning into what would soon become one of the most controlled visual cultures of the twentieth century. His square was political, though not in the straightforward sense of slogans or propaganda common back then (or, I suppose, even now).

Totalitarian power needs images it can easily read, approve of, and deploy. Under Stalin, this became the foundation of Socialist Realism, a style that dominated Soviet art for decades. Its success had nothing to do with artistic merit. It succeeded because it was simple, literal, and useful to the state.

The imagery was always the same:

the heroic factory worker raising his hammer;

the smiling peasant girl holding a sheaf of wheat;

Lenin pointing confidently toward the future;

soldiers marching in perfect formation.

In fact, on a recent trip to former Soviet states, I managed to go through the archives in the art museums of much of Malevich’s contemporaries’ propaganda at the time, and yes- it felt incredibly uniform. Which, I suppose, was exactly the point.

These pictures required nothing from the viewer except recognition and agreement. They reinforced a single, authorised vision of the world without ambiguity, dissent, or (importantly!) interior life. Everything was clear, positive, and purposeful. You knew exactly what you were meant to feel.

Malevich’s Black Square, by contrast, offered none of that. It was illegible. It didn’t tell you what to think, or why. It refused the comforting clarity of Soviet heroes and wheat fields and radiant factories. It opened a space where meaning was not given but had to be created by the viewer. And in a political system built on controlling perception, that kind of perceptual freedom was… dangerous?

We saw the same fear of ambiguity elsewhere: Hitler labeled Kandinsky and Mondrian as “degenerate” because abstraction allowed for individual interpretation, which was something fascism could absolutely not tolerate!

Art that opens space for ambiguity or alternative ways of seeing is art that slips out of state control. Suprematism wasn’t incompatible with Stalinism because it was elitist; Stalin didn’t care about that. It was incompatible because it was ungovernable, and because it generated perceptual freedom the regime had no way to contain.

Malevich, by all accounts, understood this intuitively. He was outspoken in believing that abstraction was the visual language of a new, liberated consciousness.

The New Crisis of Representation

So here’s why Kazimir Malevich’s book stopped me in my tracks this week:

It had been years since I’d seen or really looked at his work, and yet seeing it in a world far more chaotic and visually overloaded than the one I first encountered him in? Its meaning felt almost… eerily relevant.

Malevich is relevant again! He matters more now than ever before because the crisis he was responding to in 1915 has returned, not as an art problem but as a full-spectrum condition of life. Back then, the world was being unmoored by war, technology, revolution, scientific upheaval, and the sudden collapse of the existing social order. The political, aesthetic, and philosophical infrastructure and narratives people had relied on could no longer hold the world together.

And the terrifying part is how familiar that feels now.

Today the rupture arrives somewhat differently, of course. It isn’t just that we’re surrounded by too many images (which we are); it’s that every part of our lives feels saturated, sped up, destabilised. The onslaught of technological disruption shifts us so quickly that our frameworks for understanding can’t keep pace. As I wrote recently, AI forces us to question not only what is real but what counts as human. Politics feels unmoored. Economies wobble in, but mostly wobble out, of coherence. Scientific discovery accelerates faster than our moral or perceptual systems can process. And beneath it all is this fucking impossibly disorienting noise converging around outlandish volumes of input, information, and intelligence forms for which we have no interpretive tools.

The problem is not even that it’s just our representation failing us. Add to this that we no longer have a clear sense of the world we are trying to represent. Our current experience outpaces our comprehension of what it means to be. Meaning doesn’t have time to insert itself in our lives before we’ve moved on to the next thing. We push through a reality we cannot fully see, let alone describe.

In a world this chaotic, Malevich’s austerity feels like a guiding principle that we should probably pay more attention to. His work suggests that when everything becomes too overwhelming to understand, the solution isn’t to add more (more images, more detail, more explanation, more data, more everything), but to take things away. To strip back the noise. To return to the basics of perception. To feel, and see, and hear. To rebuild our sense of the world from simple, grounding elements.

Not to see the world as it’s constantly presented to us (because that’s pretty indecipherable right now anyway), but to notice our own ability to make sense of things amongst the noise.

As Malevich has told us: The Black Square is a starting point, not an ending. It’s a question about what new forms we’ll need to create in order to understand the world that’s emerging, and whether we’re brave or willing enough to create them.

Perhaps it’s time that we all became Malevichian minimalists.

Absolute superb work. Well done and thanks a lot for sharing. I generally see many similarities of thought processes between the early 20th centuries art movements and today’s world (futurism and the believing in technology and industry ruling everything and leading to a war between the new and the old as another example). Maybe exactly because back then the limits of thought frameworks appeared in a similar matter as today.