Silicon Valley: A Paradox of Civilizational Scale

The Fragility of a Power Without Culture

Silicon Valley remains a paradox.

Consider that it now operates at civilizational scale in that it shapes markets, institutions, and collective imagination, while wielding power comparable to that of states through its venture mercantilism. It writes our industrial strategy, drafts our legislation, builds our infrastructure, and imagines the future on behalf of everyone else.

But also consider that what distinguishes it from every historically durable system of similar reach is that it was built without the civilizational foundation of… culture.

Because beneath the theater of innovation (wow, venture capital puts on a hell of a good show), and the ocean sized flows of capital lies a foundational absence: not of capital or coordination, but of the symbolic architecture that allows institutions to endure.

And this is an absence so complete that Silicon Valley does not even recognize it as a loss.

Stepping back briefly, my economics research has recently focused on a deceptively simple but incredibly important hierarchy:

Culture → Institutions → Markets.

Culture is the symbolic substrate that gives meaning to a society’s institutions; institutions coordinate that meaning into rules and governance; markets are merely the visible layer that sits on top. When the symbolic layer weakens through cultural demise, institutions drift. When institutions drift, markets become volatile. Collapse (whether fiscal or societal or organizational) begins not in prices or policy failures, but in meaning itself.

Economists, however, tend to ignore this first layer almost entirely. There are, of course, several reasons for this, but mostly because culture cannot be econometrically domesticated (meaning: modeled mathematically) and so we all have to pretend that it doesn’t really make a difference. Yes, I know.

But… it does make a difference. An important one! (and my research dating as far back as my time at MIT, actually tries to quantify this!).

Anyway, my research about culture → institutions → markets, when viewed through the lens of Silicon Valley, shows something equally important (and, I suspect, existential):

Silicon Valley has institutions, and it has markets. But it does not have culture.

And perhaps his is where my argument tends to meet resistance, because Silicon Valley is widely perceived as having a very distinctive “culture”, i.e. a recognizable “vibe”, aesthetic, and set of shared beliefs.

But I don’t actually mean culture here as in office aesthetic or founder lore. I mean culture in the civilizational sense: the deep symbolic architecture through which communities make meaning, propagate memory, stabilize their identity, and survive crises.

In short, my research suggests that systems composed of institutions and markets without an underlying cultural layer are structurally fragile over the long run.

And while these systems often perform exceptionally well during periods of expansion, they become acutely vulnerable to shocks because they lack the symbolic ballast required to absorb disruption without losing coherence.

Which means the following:

Silicon Valley may be one of the most powerful ecosystems in the world, but it is also one of the most fragile.

This becomes especially clear when contrasted with two systems whose endurance was not based on technological but cultural progress: the Catholic Church and Renaissance Florence, both of which possessed immense influence, shaped global history and endured (and continue to endure!) through their symbolic architecture which runs far deeper than the institutions they built or the wealth they accumulated.

In this piece, I want to show you that Silicon Valley, by contrast, is a civilization-scale power built with precisely zero civilizational foundation, making it an outlier in the history of large-scale political and economic ecosystems. In fact, possibly the only one to emerge with no cultural substrate at all.

You see, Silicon Valley’s greatest existential threat isn’t regulation, or China, or even technological failure. Its greatest existential threat is that it was built without the layer that makes ensures endurance: culture

What Culture Actually Is

To understand Silicon Valley’s structural vulnerability, it is necessary to specify what culture means within the hierarchy I just shared: Culture → Institutions → Markets.

So in the context of economic systems, culture is not simply the coming together of aspects such as lifestyle, company norms, or aesthetic preferences. Instead, it actually functions as what Douglass North (Nobel Prize winner) would describe as the “informal constraints”, or the shared symbolic and interpretive frameworks that make formal institutions cohesive

In other words, culture is the deep coordination mechanism that must exist before law, contracts, and markets can even begin to function. It brings together our collective expectations, how we interpret the world, and legitimacy structures that therefore allow the institutions to operate and markets to equilibrate.

And so without this symbolic architecture (read: culture), weird things tend to happen in the world of economics! Such as: incentives lose their meaning, enforcement loses credibility, and market signals lose touch with the social realities they are supposed to reflect.

If, by the way, you’re thinking these outcomes sound scarily relevant to our society writ large today, then yes! And in much the same way that we are trying to solve coordination problems with distribution solutions in our political economy, we often misdiagnose our societal problems as structural, institutional ones. But they are not; they are cultural thorns!

In very economic terms, culture provides:

Shared memory: continuity that forms the basis for repeated cooperation and equilibrium.

Rituals: standardized behaviors that reduce transaction costs and stabilize expectations.

Obligations: normative commitments that supplement formal enforcement

Logic: underlying assumptions that frame what is considered valuable, productive, or legitimate

Intergenerational continuity: the mechanism through which norms persist, enabling long-term institutional durability.

Identity: a stable reference point for cooperation, preventing the unraveling in the face of shocks.

Legitimacy: the cultural foundations of compliance, without which institutions have to rely excessively on costly monitoring or enforcement.

Temporal orientation: a shared framework for interpreting uncertainty, risk, and long-run investment

So clearly, within this structure:

Institutions = the formal systems that translate cultural meaning into actual rules for how society works (laws, regulations, bureaucracies, property rights).

Markets = sit on top of those institutions and only function when there are stable rules, enforceable contracts, reliable information, and predictable expectations.

Thus the hierarchy is not rhetorical; it is indeed very structural:

Culture → Institutions → Markets

And has dynamics that roughly follow the below:

When the cultural layer weakens, institutions lose legitimacy, compliance declines, and the coordination functions they provide begin to drift.

When institutions drift, markets become increasingly narrative-driven, speculative, and vulnerable to what Akerlof and Shiller call “animal spirits.”

Under institutional drift, markets lose their anchoring heuristics and become prone to collapse.

Now, as I’ve mentioned in many other posts, a system without culture can look perfectly healthy during boom times, because growth and liquidity tend to hide structural weaknesses extraordinarily well! But when real shocks arrive, all systems tend to struggle, regardless of how healthy they are: perhaps they can’t absorb disruption, or correct errors easily, and they end up losing coherence over the long run.

Systemic collapse in this manner often doesn’t happen all at once. Instead, collapse appears gradually, through higher volatility, falling trust in institutions, and markets that become more unstable over time.

However, in debates about how markets form or how industrial strategy works, this cultural layer is usually ignored, mostly because it’s so hard to model. Yet the evidence is clear: markets are more durable when strong culture sits beneath them! And when that cultural foundation is weak or missing, markets swing wildly, institutions lose credibility, and entire ecosystems start to follow stories and hype rather than real fundamentals.

So here’s the main point: contrary to common belief, Silicon Valley stands out not because it has an unusual culture, but because it has no civilizational culture at all.

This makes it the opposite of every historically durable ecosystem, from the Catholic Church to Renaissance Florence, and leaves it far more exposed to future shocks than its current power suggests.

As in- the Silicon Valley élite may function as our Overlords today… But it’s highly unlikely that Peter Thiel will be giving lectures on the antichrist to a much adoring crowd while deciding who resides in the White House tomorrow.

The Catholic Church

To see what Silicon Valley lacks, it helps to look at a system where culture is unmistakably the primary layer: the Catholic Church. And regardless of whatever one thinks of its theology or its politics (and trust me, I have many, many thoughts), the Church does remain one of the most durable institutional ecosystems in human history.

I mean, consider that it is more than 2,000 years old, has spread across continents, and has survived schisms, plagues, wars, reformations, and dramatic epistemic shifts (as well as its own centuries of absolute self-sabotaging).

In fact, there are very few institutions, religious or secular, that have matched this longevity. But why has it endured?

Simply, because its foundation is not directly connected to its bureaucracy, its capital, its political structures, or even its hierarchy; these are all secondary. Rather, the foundation of the Church is its culture in the deepest civilizational sense.

Long before it built administrative systems or accumulated its massive wealth, the Church articulated a belief system that provided a logical account of human purpose, alongside a canon of texts that fixed those beliefs into an enduring intellectual tradition. Similarly, it created a symbolic vocabulary that allowed entire societies to interpret our greatest possible human states: suffering, authority, obligation, and hope through a common lens.

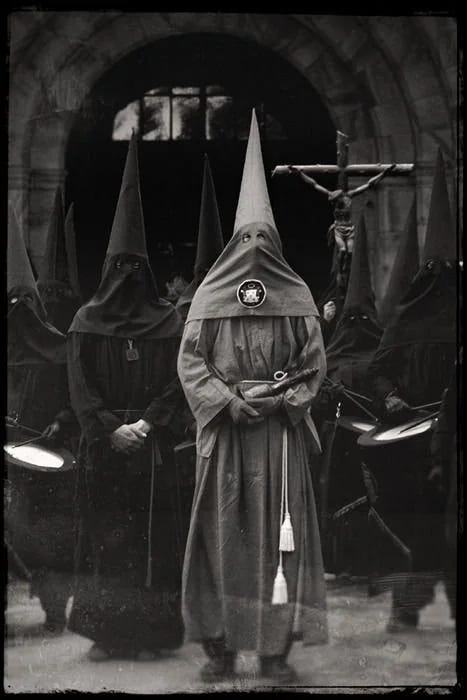

Its stories shaped identity and did the heavy lifting of telling communities who they were and how they were situated within a very specific moral universe. Its rituals encoded meaning through repetition (Mass? Baptism? Confession? Rosary beads?), reinforcing a sense of belonging that transcended time and geography. Its doctrine offered a rigorous theory of moral responsibility that tied individual life to collective obligation.

Importantly, this is not unique to the Catholic Church as a whole! As Gareth Gore wrote in his (excellent!!) book “Opus” on the formation of Opus Dei, religious systems that endure rarely begin as bureaucratic projects. Indeed, Opus Dei began by constructing a deep philosophical and cultural domain long before its founder considered creating a formal organization.

In the case of Opus Dei, the cultural groundwork preceded institutionalization by many years. This early emphasis on meaning, theology, and identity gave the later institutional structures its durability and coherence.

Thus we can see, as demonstrated well by religion: Institutions are downstream of culture, not the other way around!

So successful religions have shown us that symbolic architecture comes first, in the form of culture, and it is from this very foundation that the Catholic Church’s extensive network of institutions eventually emerged.

Those institutions, by the way, were (are?) insanely sophisticated. Parishes for creating local governance; monastic orders for centers of learning, agriculture, and preservation; and canon law to take norms and turn them into formal constraints. They weren’t random bureaucratic inventions! They were built directly out of the culture people already shared and trusted.

From these institutions, in turn, came the Church’s markets: its economic systems.

I.e. incredibly large landholding, control of labor, patronage that funded art (and thus controlled the narrative), regional economic markets structured around the Church’s calendars and authority, charitable giving that exerted even more control. The Church’s economic life was the final layer in a cultural–institutions hierarchy that made its markets unusually stable for… centuries.

So this is why the Catholic Church has survived almost everything (except modernization, and even that is simply eroding it slowly rather than destroying it outright). Because the Church’s cultural foundation is extraordinarily deep, that the system can absorb crises, reinterpret its past, and re-legitimate its institutions.

In other words: where culture is strong, the system endures.

Renaissance Florence

If the Catholic Church shows us how culture produces endurance, Renaissance Florence shows us how culture produces innovation– another quality Silicon Valley claims as its own.

In fact, it is the clearest historical example of what an innovation ecosystem looks like when it is grounded by a foundation of culture that gives coherence and direction to creativity.

Florence, if you have never been, is an incredibly and remarkable place. Not only because of the art and wine (which… yes, the wine), but because you can still see, to this day, the miraculous extent of early innovation that brought humanity out of its Dark Ages. I mean, in the span of a few generations, Florence produced:

The Renaissance itself

Modern banking and financial instruments,

Constitutional experiments that shaped later republican thought,

Art that entirely redefined humanism (Giotto, Donatello, Botticelli, Michelangelo!),

Scientific and mathematical breakthroughs,

Literary revolutions from Dante to Petrarch to Boccaccio.

Honestly, this is one of the most extraordinary concentrations of innovation in human history. But again, how did we get there? Clearly, none of it emerged from an institution vacuum alone.

The infamous Medici family which controlled the region did not conjure a Renaissance by merely inventing “banking”. Nor did the guilds produce artistic revolutions simply by creating apprenticeship contracts. And the Florentine republic did not produce new political forms solely through throwing together new ideas about constitutional design.

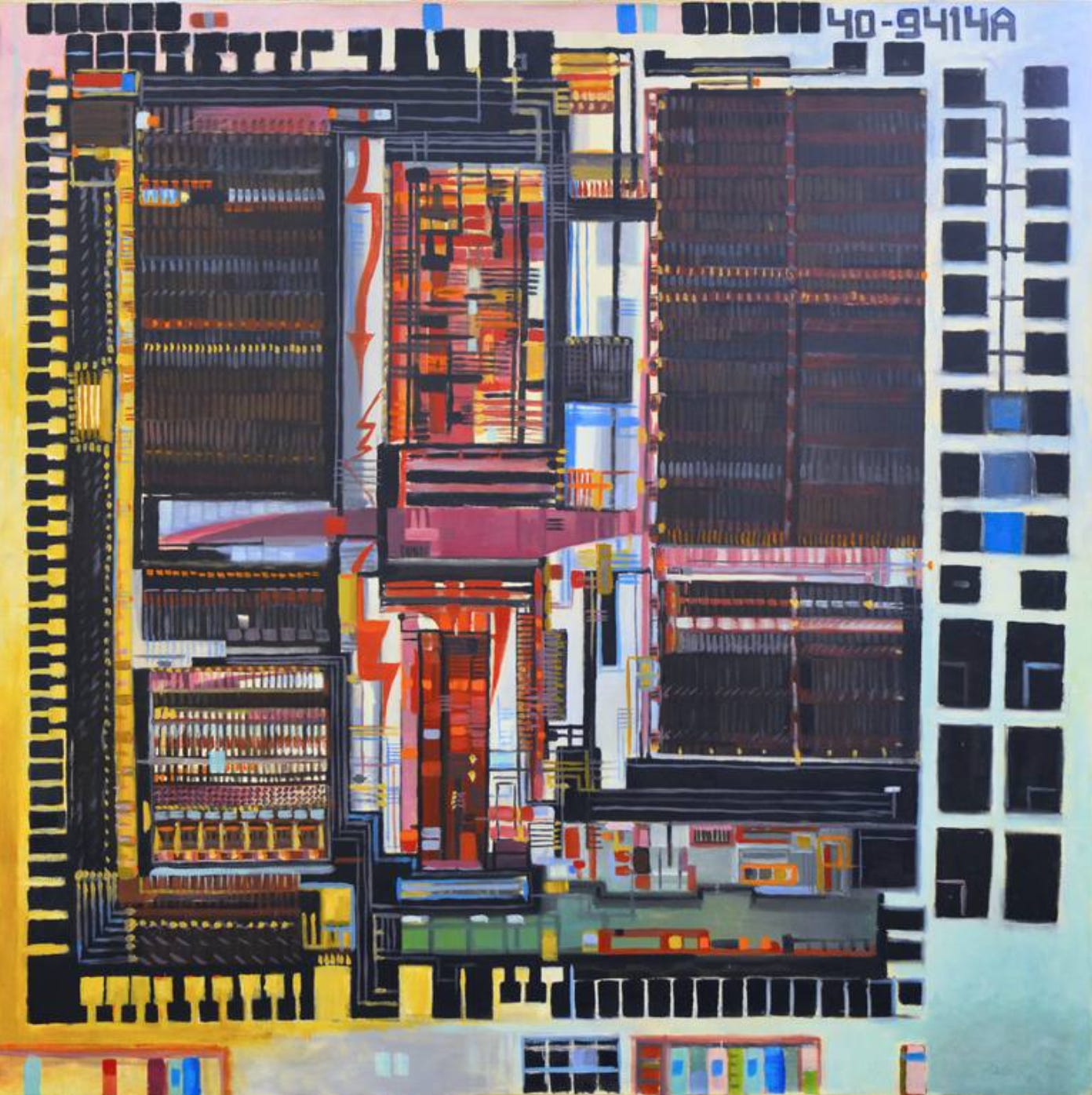

Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781

In short, Florence innovated because it was held together by a deep cultural substrate, which included:

Shared civic identity: rooted in pride, rivalry, and collective belonging,

Symbolic world: that blended Christianity, classical revival, and local belief into a coherent logic,

Humanist philosophy: recentering the dignity and agency of individuals within history,

Guild structures grounded in tradition: that transmitted craft knowledge across generations,

Rituals of patronage: linking wealth, prestige, and public contribution,

Dense memory infrastructure: Dante’s Commedia, Petrarch’s sonnets, civic chronicles all provided a shared account of what Florence was and what it aspired to be.

Thus we can see that Florentine innovation was not simply produced at will.

Rather, it was culturally metabolized. Specifically, its institutions had ballast because they were anchored in a shared beliefs and symbolic order. Likewise, its markets had orientation because economic activity was embedded in deep civic narratives and obligations. And thus its elites (merchants, bankers, artists, philosophers) were shaped by symbolic depth, because they were educated in a worldview that prized continuity, excellence, and public meaning.

Which is why Florence’s achievements endured far beyond the lifespan of its political stability, which it had very little of. In fact, the city went through coups, foreign invasions, internal factional violence, economic collapses, and the rise and fall of ruling families (you name it, it happened in Florence!). Yet the cultural foundation beneath it was so robust that the innovation economy strengthened, not weakened, even as the political system faltered.

And this contrast is crucial for the purposes of this essay:

Florence innovated at a civilizational scale because it was not culturally hollow. Whereas, Silicon Valley innovates at civilizational scale while being culturally hollow.

You see, Florence had symbolic depth long before it had institutional sophistication. On the other hand, Silicon Valley has tried to create institutional sophistication without symbolic depth.

That asymmetry is the danger that is posed to the West Coast innovation ecosystem now!

So while Silicon Valley may indeed have extraordinary material power, it has no narrative, belief system, or moral architecture capable of stabilizing that power over time. Hence, while the Renaissance era shows us what happens when innovation is grounded in culture; Silicon Valley shows what happens when it is not.

Institutions Without Culture Die

Again… If the Catholic Church shows how culture produces endurance, and Renaissance Florence shows how culture produces innovation, then Silicon Valley illustrates the opposite phenomenon:

What happens when a system is built almost entirely without culture.

Applied to the same hierarchy I have discussed so far (Culture → Institutions → Markets), the contrast is stark.

I mean, Silicon Valley undeniably possesses institutions. Its firms, venture funds, accelerators, and governance structures are among the most sophisticated organizational systems we have today. Indeed it also possesses extraordinarily powerful markets, fueled by vast liquidity and investment cycles that continue to reshape entire industries at speed.

And it has an ideology, yes. A volatile mix of libertarianism, techno-optimism, accelerationism, and heroic individualism, all that structures its self-understanding.

So wrapped around all of this is a striking narrative self-image: of the Valley as frontier, as a sovereign actor (again: venture mercantilism), and as the engine of civilizational progress.

But what it does not have is culture in any civilizational sense!

There is no symbolic world beneath these institutions that gives them meaning, coherence, or legitimacy. Instead, the Valley relies on a set of cultural proxies (think: thin imitations of culture that cannot shoulder the weight that real culture carries, such as Allbirds sneakers or Patagonia vests worn ironically).

Similarly, its anti-mainstream (now turned very-mainstream) ethos is mistaken for a belief system. It has an extraordinarily adolescent literary canon which is often confused and blended into the ecosystem’s idea of a political economy. Its belief in the “exceptional individual” replaces any real sense of shared obligation, and its worldview comes more from science fiction than from humanistic or philosophical traditions.

The result is a system that is extraordinarily busy, sure. It’s full of action, ambition, and narrative (and draaaama) but strikingly empty of… meaning! Silicon Valley has all the narrative and ideology, but none of the memory or culture. And its institutions function, strangely, without the symbolic foundation that would allow them to endure.

In short, Silicon Valley built a market first consisting of IPOs, M&A, and financing; backed some institutions into it through venture funds, and simply skipped the cultural foundation that makes such systems durable.

Although, people often mistake its ideology for culture. It has a specific worldview, yes, and a set of shared myths, and so it confidently assumes that it possesses a civilizational foundation. But these are ideological formations, not cultural ones. And allow me to be clear about the difference:

Ideology tells a community how to understand power

Culture tells a community how to understand meaning.

For example, the Valley’s literary canon (by which I mean the same five sci-fi books that are narrowly interpreted) lacks the elements that make a symbolic world durable: beliefs, rituals, memory, intergenerational transmission, ethical weighting, and any vocabulary for the ordinary, the communal, or the non-heroic. Yes, the Valley can generate identity, but we have never seen this lend itself to continuity, or wisdom, or an idea of what constitutes good citizenship, or how to engender this to legitimacy.

This, ultimately, is why Silicon Valley can build rockets, autonomous weapons, and planetary-scale compute systems, but struggles to comprehend or have a working model that understands civic trust, public institutions, political continuity, ecological responsibility, or any world in which non-elites feel seen.

Yes, Silicon Valley has extraordinary capacity, but it has no cultural architecture to stabilize or orient that capacity!

When Markets Detach from Meaning

It turns out that institutions built on a vacuum behave in predictable ways!

They become brittle, because nothing beneath them absorbs tension or contradiction. They become volatile, because expectations have no shared narrative to anchor them. And over time they become short-termist, because the future lacks the symbolic definition that would allow leaders to justify long-range tradeoffs. And they become unusually vulnerable to ideology, because in the absence of culture, ideology is the only story left to organize collective action.

Even worse, when the cultural layer is missing, this fragility cascades through the entire system.

Venture capital accelerates this dynamic, leaving its financial markets in a very strange place.

Remember the SpaceX Roadster in space? Sigh.

In the absence of culture, venture capital institutions themselves begin to drift. With no symbolic or normative framework to anchor judgment, venture funds lose any stable reference point for legitimacy, time horizon, or purpose. And yeah, this feels obvious right now! The VC financial markets follow accordingly, becoming increasingly responsive to sentiment, narrative momentum (“vibes”), and nonsensical displays of over-confidence (!) rather than to underlying fundamentals.

This clearly results in what we see today: surface-level narratives that spill across every investment domain. And with no deeper cultural framework to interpret them or integrate them into a coherent philosophy of value, stories begin to substitute for actual analysis. Insane amounts of liquidity and capital into the VC markets does nothing to help this dynamic, of course, and actually amplifies it, turning humungous portions of the market into speculative feedback loops.

So under these conditions, “innovation” no longer generates material or social progress. In fact, it becomes little more than a weak financial signal, whereby “progress” is conflated with “capital deployment” and high valuations, rather than by technological contribution to society.

At a certain stage, bluntly, you start to see weird shit happening as the institutions and markets in Venture Land distort radically, like CEOs tweeting national strategies on behalf of the White House, and founders acting as if they are heads of state, and CFO’s of large AI companies suggesting the government considers bailing out their multi-trillion dollar hiccups.

All that is to say, when a system has no cultural ballast, crises become self-fulfilling.

A downturn becomes less about something that is survivable, and more about a “reckoning” that is irrecoverable (Silicon Valley Bank, cough). A local political conflict becomes an “existential threat” to the Valley pretty quickly (JD Vance, cough). A technological setback becomes a story of doom or destiny, but never just something in between.

In short, the system cannot absorb shocks because it has no symbolic architecture to hold them! Which in turn creates an internal whiplash that makes the system prone to collapse at any moment.

This, I suppose, is what I am trying to describe as Silicon Valley’s existential threat:

That it cannot survive a crisis of meaning because it has no symbolic world resilient enough to absorb a crisis.

And we’ve seen how these civilizational-scale powers end before, many times over: they collapse first in their culture and their beliefs and sense of shared purpose, long before their institutions and markets die.

However, in this instance it’s not that Silicon Valley has already collapsed in that domain, but that it never really had anything there in the first place. I mean, its institutions and markets are powerful, yes, (a16z is not going to disappear anytime soon), but they are also symbolically… empty.

And this is a structural issue for Silicon Valley with consequences for the entire society now built atop Valley technologies. Silicon Valley increasingly functions as the de facto imagination engine of the US, shaping industrial policy, defense strategy, data infrastructures, media ecosystems, and the very conception of what “the future” is. But it does so without possessing the philosophical depth that historically allowed other civilizational centers to guide collective life.

Florence’s Renaissance and the Catholic Church endured because their innovations and institutions were metabolized through thick cultural worlds, but Silicon Valley lacks all of that. I mean, sure, it can generate unprecedented power, but it cannot stabilize the world it generates. Hence it screams for bailouts as soon as something goes wrong.

And yes, it can build systems that restructure society, but no, it cannot provide the symbolic coherence to hold that society together.

The danger is therefore not merely that Silicon Valley will fail. The danger actually is that the Valley will succeed, and become more powerful, as we see today, but in ways that unmoor the wider political economy… simply because it lacks the culture required to interpret, constrain, or legitimate its own power!

Thus, a world in which we outsource our power and imagination to an ecosystem with no symbolic weight may be technically sophisticated but ultimately it leaves us socially incoherent.

Unfortunately, our collective future through this lens has already been optimized for scale, but it is impossible to optimize it now for meaning.

And so while Silicon Valley is powerful enough to build the next world that we’ll all have to live in under Lord Musk’s reign, it is doing so without the civilizational architecture that makes worlds durable.

You see, power without culture can certainly create a new world order. But it cannot make one last.

Loved this. 🎯 The model propagates not as a design flaw, but as a perverse mindset. One where its local champions perceive themselves as independent of, rather than embedded in, a broader coherent community.

With the deepest respect, I disagree on this.

I've really enjoyed almost everything of yours that I've read so far, but this one post comes across as an outsider's view. It conflates the presently most visible individuals within Silicon Valley (Thiel, Musk, Andreeson etc.) with Silicon Valley itself, and I'm not sure that would resonate with anyone who has been on the ground there for any length of time. Some proximity may be seen in software, but the description really doesn't mesh at all with the more durable Semiconductor industry that forms the Valley's roots, and is foundational to the regional economic culture.

Another model one could try would treat these as conquering invaders imposing themselves and their values on a longstanding ground-level culture with values very different from theirs. That culture does possess all the elements of economic culture you list (that's how it grew in the first place). However, due to capture (first financial-sector, then regulatory, then political) from outside and above, that culture is no longer calling any shots, at least not to an extent readily discernible from a distance, as the invaders are all that can be seen on the news.

These extractive invaders are as ideologically and culturally isolated from most of the Valley, for which they have active disdain, as they are from the rest of the world. Perhaps even more so.

Imagine as an analogy Putin's claim that he is defending Russian-speaking Ukrainians when he invades their land and starts killing them. He's claiming shared culture, but that's only to justify the wanton destruction and resource extraction from that same territory. It's the fiction that justifies the theft.

To accept the fictional framing is to be complicit in enabling the aggressor. But if the foundational culture can be freed from its parasitic overlords, both meaning and innovation can still return, to general benefit.

A key cultural difference lies in the nature of the problems being solved. The scope of technological problems in software is bounded, finite, and knowable in Turing-complete systems such as software. So it is possible to pitch or invest in something with nothing more than an idea, and have that work out, often enough. Thus the spin can wind up being all-important.

In hardware, the problems are expensive, and grounded in physics and engineering problems that are generally not bounded in difficulty. It is not just the finite-cost path to a solution that needs to be established, but the very existence of one. That means evidence-based reasoning dominates. The distinction drives profoundly different cultural forces. Extreme financialization can extract more value from the hype cycle if the talk-heavy, low-risk software culture dominates, so that's what gets fed preferentially by the financial sector, even while the hardware-shaped Deep Tech culture powers the productivity engine.

External physical reality forces you to mark-to-market. Vaporware doesn't.

It is financialization as a tool for cultural capture that drives the dynamics you cite. The engineering ethos is being drained by the vampiric investment banking one. Silicon Valley isn't hollow, but it is under attack, and like Ukraine ... losing due to insufficient broader awareness.