The Mirage of Compensation

Rethinking Globalization: On Branko Milanović’s "The Great Global Transformation"

I decided to finally read Branko Milanović’s latest book after being reminded to do so when it became the topic in this excellent Nicholas Mulder post on Two Great Transformations.

And I can see why this book, The Great Global Transformation, won the Financial Times book of the year last year. It is excellent.

For those who haven’t come across him, Milanović is arguably the world’s foremost authority on global income inequality, and he’s earned that title the hard way. Born in Communist Yugoslavia in the 50’s, he grew up watching the 1968 student protests from the edge of the University of Belgrade campus, where kids in red Karl Marx badges chanted “Down with the Red bourgeoisie!” while he wondered whether his own family (his father was a government official) belonged to the group being denounced.

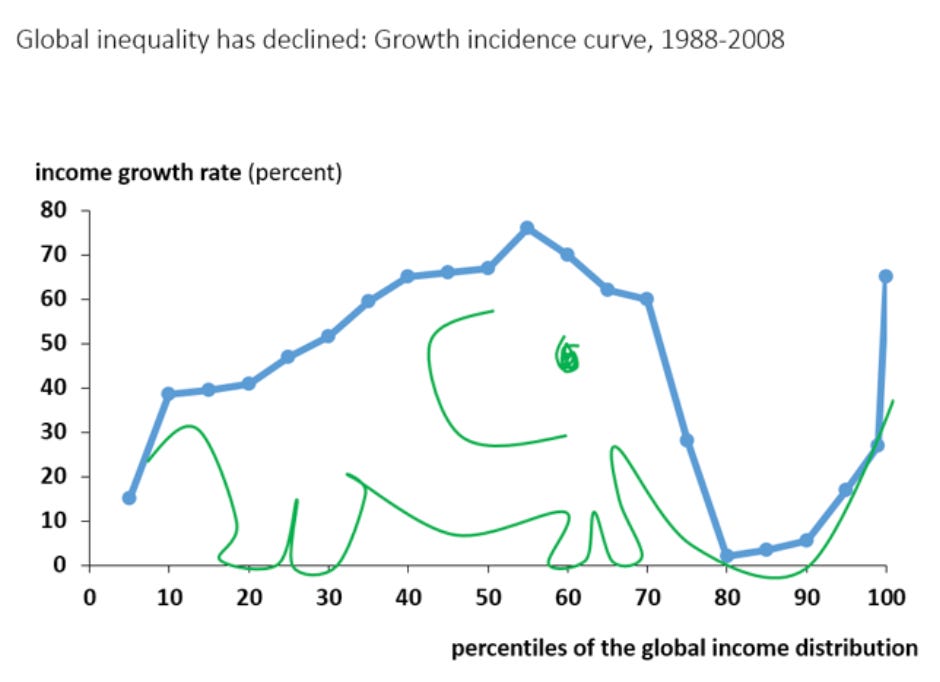

His early experiences of the contradictions of class became his life’s work. He is now at the Stone Center on Socio-Economic Inequality at CUNY and LSE, where he created the infamous “elephant chart” which changed how an entire generation of economists talked about the global middle class. Thus, he showed that the gains from trade had flowed spectacularly to Asian workers and Western elites, while Western working and middle classes were squeezed into a slow, grinding stagnation.

His previous books (e.g. Worlds Apart, Global Inequality, Capitalism, Alone, Visions of Inequality) have built the most rigorous empirical case that exists for why inequality matters, how it moves, and what it does to political systems when left unaddressed.

To be sure, Milanović is an extraordinary thinker who frequently writes some of the most compelling accounts of globalization’s fallout that exists, mapping with devastating precision who won and who lost from the great opening of the world economy.

Milanović is known, also importantly, for understanding the political convulsions that followed as a consequence: Brexit, Trump, the collapse of centrist parties across Europe.

His latest book, The Great Global Transformation, extends this analysis into what comes next.

The thesis, in short: neoliberal globalization is over because it produced the very forces that killed it! It outlines:

China’s rise, enabled by neoliberal openness, grew too large to be absorbed into a US-led global order.

A newly enriched Western elite began rewriting the rules to entrench its position.

The same elite abandoned commitments to open borders, multiculturalism, and liberal norms once those commitments no longer served its interests.

The result is what Milanović calls “national market liberalism”: a world where markets still operate domestically, but the global architecture that connected them (free trade, free capital flows, free movement of people) is being dismantled by the very countries that built it.

Oh, and the political energy driving the dismantling of our system isn’t just some aberration or populist tantrum; it’s a structural realignment that is powered by the same inequality data Milanović has spent his career documenting.

The book is, in many ways, his attempt to name the era we’ve already entered but haven’t yet been able to start speaking coherently about. And it’s excellent at that. But here’s where I start to get twitchy… because the prescription that flows from Milanović’s diagnosis feels almost too self-evident. It basically says something along the lines of:

If globalization created winners and losers, and the losers were identifiable and concentrated, then the fix to this problem is… (drumroll)… redistribution.

As in: If you just tax the winners, and compensate the losers, while investing in retraining and expanding our safety nets, globalization works! In other words, had we just made the gains from this new globalized trade broad enough that the system retained its legitimacy and people were kept just about happy, we’d still be in the economic halcyon days of our recent past.

This is, of course, a smart, good-faith position that is held by many serious people, grounded in real economics, and it has the enormous appeal of suggesting that globalization itself was broadly right, but just… badly managed. And look, Milanović is not naive about this. He understands the political economy of why redistribution didn’t happen. He knows the obstacles are real.

But the underlying logic of his frame remains:

Markets produce outcomes;

Politics corrects these outcomes.

And this logic is, unfortunately, where he loses me.

The Assumption Beneath the Redistribution Story

Beneath the redistribution story lies an assumption that rarely gets examined because it feels so obvious and reasonable. And that assumption is this:

Markets decide first, and governments respond later.

In this view, the shape of the economy (as in: who produces what, where investment flows, which industries grow and which die, how risk is allocated between firms and workers) is determined by market forces. And the role of government is little more than to manage the distributive consequences of those forces after the fact.

Governments, in this framing, are clean-up crews. Markets do the fun stuff, like building the economy by deciding where the factories go, which industries grow, what gets made and where. Then the public sector sweeps through afterward with mops and checks, compensating the displaced, clearing up the inevitable fallout.

The economy itself? That’s treated as a given. Something that just happened; the natural result of “comparative advantage”, and global supply chains, and capital flows, and technology. Nobody designed it and nobody chose it. It simply emerged. (Out of what, we’re not sure, because we never discuss this).

Which means the only thing left to argue about is who gets what after the economy has already done its thing. That’s the political question that we vote on: should we have more or less taxes? Should healthcare be subsidized or not? Not: What kind of economy do we build? But: How do we divide up what it produces?

This framing is so deeply embedded in how we talk about economic policy that most people don’t even notice it operating. Yet it shapes the left as much as the right! Progressives argue for more generous compensation, of course, while conservatives argue for less. But both sides accept the same underlying division of labor: the economy produces, and the state redistributes. In this framing, the factory either closes or it doesn’t. The only question we should ask is whether the workers who lost their jobs to China or India get to be retrained as AI engineers or their homes repossessed.

And honestly? This seems reasonable. It even seems even a humble acknowledgement that markets are complex (they are!), that governments can’t control everything, and that the best we can do is soften the edges.

But here’s the thing… This isn’t just a neutral observation. It’s an assumption so deeply woven into how we think about economics that it has become invisible. And it’s the reason we’ve spent forty years arguing about how to compensate people for economic damage, instead of asking why we built an economy that damages them in the first place.

The Retreat from Shaping Economic Development

But step back for a second. Long before we were arguing about compensation, a more fundamental change had already occurred: Western governments stepped away from coordinating their own economic development.

This wasn’t accidental; it actually reflected a profound intellectual shift in how economists understood the state and lobbied for it to operate.

The postwar model had been shaped by a broadly Keynesian and developmentalist consensus, by which I mean: governments were expected to manage aggregate demand, but also to steer structural transformation. So-called boring policies of industrial policy, capital controls, sectoral bargaining, etc, were not seen as “market distortions” or overbearing government involvement, but as necessary complements to markets!

So to summarize: markets allocated within a framework, and governments shaped that framework.

By the late 1970s, that consensus was sledgehammered.

Here’s some technical jargon that, even if you don’t understand the terms, you’ve probably heard of before – all related to the enshittification of our society: neoclassical economics, rational expectations theory, and the efficient markets hypothesis. All of these drastically redefined the state’s role.

What these terms really imply is the following:

Markets are smarter than governments (of course)

Prices carry all the information we need (“it’s priced in, stupid!”)

If something is profitable, capital will flow to it (like monkey jpegs)

If it isn’t, it shouldn’t survive anyway (who needs education when you have monkey jpegs)

On this view, government intervention in the economy wasn’t just inefficient, it was actually dangerous.

And there was a second layer to the argument. Even if governments wanted to act in the public interest, could they be trusted to? Consider that politicians have incentives, just as bureaucrats have careers, and industries do what they do best: lobby. Once you start steering investment, you invite corruption, favouritism, and backroom deals. Better, the theory said, to let markets decide, and keep government small, rules-based, and mostly out of the way.

(Side note: Anybody checked on how well Nancy Pelosi’s hedge fund portfolio is doing this quarter??)

So the new common sense became simple: markets allocate resources, and governments step in when (and only when!) the market fails, but using “redistribution” to handle the fallout.

And once that new common sense took over, a new policy followed wherein governments stopped asking where factories should be located and began assuming it would settle where it was most efficient. Which really meant: they stopped worrying about the geographic distribution of industry and began trusting global specialization to generate overall welfare gains

This led to domestic industries being exposed to global competition without the parallel institutional investment that might have prepared them to compete or adapt!

And this? Was called globalization.

For capital markets, this logic delivered extraordinary results! Supply chains became globally integrated and highly efficient, meaning that costs fell and profits rose. Financial markets deepened on the back of this and became insanely sophisticated (read: leveraged). And much of the system appeared to be working exactly as intended.

And this is precisely the world Milanović describes in The Great Global Transformation.

His central claim is that globalization produced global convergence as Western middle and lower classes experienced a “positional decline” in the global income distribution, while Asian middle classes surged upward and Western elites remained at the top.

Milanović argues that this widening gap creates political strain. Democracies struggle when their citizens no longer share a roughly similar place in the global income hierarchy, but instead live in what feel like entirely different economic worlds. That tension, he suggests, fuels the backlash against neoliberal globalization and leads to a system where openness weakens but domestic laissez-faire remains.

On that, I agree. Where I differ is in how we explain why this happened.

An economy can be highly efficient and still unstable, and efficiency doesn’t decide who bears the cost when industries move or collapse. Consider that when factories relocated, capital could move, but workers could not. Similarly, when firms consolidated, investors could diversify, but towns in Middle America did not.

As a result, the insanely high costs of adjustment (wage stagnation, job loss, social fragmentation) fell in concentrated ways on the people and places least able to absorb them.

So here’s the crux of my issue:

Milanović argues that this asymmetry should have been counterbalanced through more aggressive redistribution:

Steeper taxation of winners

Stronger social provision

More serious retraining

Some sort of adjustment policies.

In his view of this story, globalization was not inherently unjust; it was simply poorly managed. He believes that if governments had been willing to redistribute more aggressively at home while remaining open to global trade, it’s possible the backlash could have been avoided.

But this framing treats redistribution as the missing corrective. And… I don’t buy that argument at all. Rather, I see something more upstream.

Because by the time redistribution even became an issue, the structural reconfiguration had already occurred. The widening income gaps Milanović writes about were not just the result of markets overheating; they reflected earlier political decisions to step back from shaping the structure of the economy. To let trade rules, capital flows, and financial incentives determine where production happened, who absorbed the shocks, and how risk was distributed.

In other words, the divergence he talks about was not just insufficiently compensated, it was structurally generated by a retreat from coordination!

Let me say that again, differently: this wasn’t a failure to write bigger checks. It was a decision to stop shaping the economy in the first place.

The elephant curve (and the national divergence that followed) does not merely show unequal outcomes. It reveals a deep and structural design choice, that markets would determine economic structure, and politics would be confined to cleaning up after them.

Milanović’s conclusion, however, is more… restrained.

In his perspective, globalization did not have to produce this fracture, and the hollowing out of American society was not some inevitable feature of free trade. He believes it would not have happened if we were willing to tax the winners more aggressively, strengthen social insurance, and invest seriously in retraining.

In his account, the tragedy is not that globalization occurred. It is that it was not accompanied by sufficient redistribution.

Again, this is simply wrong.

Redistribution, The Great Mirage

There’s a cruel irony in that the same structural changes that made redistribution more necessary also made it less feasible. Think about that for a second!

The government’s retreat from coordinating the economy didn’t just create losers, it systematically weakened every institution and political coalition that might have delivered compensation to such losers. A blinding double whammy.

Unions, which had once given workers collective bargaining power and political voice, were purposefully degraded by deliberate policy choices about labour law, and trade exposure! Regional cities and towns that had created middle-class communities lost their economies when industries moved or closed, and with them went the tax bases that funded local services. Political coalitions that used to unite workers across sectors fragmented as economic interests diverged into the “K-economy”; some workers integrated into the new global economy, while others were fully abandoned by it.

Unsurprisingly, trust in government eroded because the government had visibly failed to protect them. The welfare extensions were means-tested into oblivion. The compensation, where it existed at all, arrived years late, cents on the dollar, and wrapped in the bureaucratic indignity of proving you deserved help.

Consider that after the 2008 crisis, financial institutions were stabilized with unprecedented speed and scale while household relief moved far more slowly, if at all. The message was loud and clear: Wall Street was important; Main Street was not.

And so it turns out, as we see today, that you cannot gut the labor movement and then expect redistribution to remain politically easy.

In the same way that you cannot hollow out regional economies and then wonder why local tax revenues can’t fund adjustment programmes. And you cannot let capital flow freely across borders while keeping workers pinned to dying towns (and then express surprise that the resulting politicians wear MAGA hats!)

Redistribution didn’t fail accidentally, it was set up to fail. The structural decisions that created the need for compensation simultaneously destroyed the capacity to deliver it. In other words, redistribution is not just politically fragile under neoliberal globalization, it is made structurally nearly impossible by it!

The architecture of globalization that produced the inequality also restricts Milanović’s proposed solution to globalization.

Milanović sees elements of this. I mean, he is too careful an economist to ignore institutional erosion. But his analytical center of gravity remains distributive: that globalization produced real gains and real losses, and that the failure lay in not transferring enough from the former to the latter.

I am making a different claim.

The primary failure was not distributive, it was coordinative.

The problem was not simply that we failed to compensate those displaced, it was that we redesigned the economy in ways that made large-scale displacement inevitable, before asking redistribution to repair consequences that had already been structurally locked in.

When the focus remains on transfers (how much compensation, through what programs, funded by which taxes), the underlying architecture of the economy is treated as a given. Thus, devastation is accepted as the starting point! Therefore the debate becomes about managing the aftermath.

My argument is that the aftermath was produced upstream by political unwillingness to be involved with how markets should be organized in the first place.

The Missing Task: Coordination

So what was abandoned? Coordination.

Which does not mean governments deciding how many tonnes of steel to produce or which colour of car to manufacture. By coordination I mean something far more modest and far more essential; that governments take deliberate responsibility for a set of decisions that markets, if left to themselves, will not make well:

Aligning what an economy produces with the skills its people actually have.

Sequencing the opening of markets with the development of domestic capacity to compete in them.

Anchoring investment (long-term, patient capital) to a country’s development needs rather than to the quarterly returns.

Deciding, explicitly rather than by default, how the risks of economic change are shared between firms, workers, communities, and the state.

This coordinating role actually used to exist! It was imperfect, sure, and sometimes captured by the wrong interests. But it was present. Postwar industrial policy in Europe, Japan, South Korea, and even the United States involved governments actively shaping their productive economies by steering investment, building institutions that linked education to industry, managing trade exposure, and creating frameworks in which markets operated but did not dictate.

This is not simply a historical observation, and it matters now because the redistribution frame does more than misdescribe the past. It actually constrains how we think about the present.

When we focus exclusively on redistribution, we sadly lower our expectations of what governance can and should do.

Every political debate becomes a fight over transfers: how much, to whom, funded by what tax. And the deeper questions? What kind of economy are we building? Who does it serve? How are its risks distributed? What role does the state play in shaping its direction? These simply do not exist.

Unfortunately, this narrowing of political imagination arrives at precisely the moment when coordination is again unavoidable. Consider our current reality:

Climate transition cannot be managed by redistribution alone. It requires deliberate decisions about which industries to build, which to phase out, where to invest, how to retrain, and on what timeline.

Supply chain resilience, a concern that was theoretical before Covid and is now very fucking real, demands that governments think strategically about production, not just trade.

Artificial intelligence will reshape labor markets in ways that no amount of after-the-fact compensation can adequately address if the restructuring itself is left entirely to Sam Altman (lol).

Geopolitical competition has made coordination not just desirable but inescapable. Governments are already intervening through industrial policy, trade restrictions, strategic investment, but they are doing so without the institutional infrastructure, the skills, or the political language that coordination requires.

The redistribution frame, for all its compassion and do-goodery, keeps us trapped in a reactive posture. It asks: how do we soften the blow?

When the real question is: why are we allowing the blow to land in the first place?

What Milanović’s Frame Misses

Milanović is right about the harms of neoliberalism and global trade, of course. He is right about the stakes, and his incredible documentation of globalization’s uneven impact is essential reading. His insistence that the political consequences of inequality are real and dangerous is a corrective to decades of complacency.

But his solution reflects such a sad and thin vision of the government’s role than the scale of the problem demands. Where I hesitate with his most recent work is in the scale of the remedy.

The redistribution-as-a-solution frame treats economic structure as something that happens first, and that politics must then manage second. It assumes the productive architecture of the economy is largely given, and that the task of government is to soften its distributive edges.

But… What if the deeper lesson of the past forty years is different?

What if it is not only that we failed to redistribute sufficiently, but that we withdrew from shaping economic development in the first place? That we ceded decisions about investment, industrial geography, and risk allocation to market forces, and then expressed surprise when the social consequences were destabilizing?

Milanović blew the door open by documenting who won and who lost in a most spectacular fashion. But perhaps the question that remains is larger: not simply how to compensate those who lose, but whether democratic governments are willing to reclaim responsibility for structuring the economy itself, to minimize the existence of losers in the first place.

In short, redistribution only manages consequences. Surely our collective power can do more, like shaping trajectories through coordination?

If neoliberalism is truly over, the challenge is not only to divide its gains more fairly, but to decide, collectively, what kind of economy we want to build next.

Sinead, I am ever impressed by the clarity of your analyses -- Thank you!! I wonder if Milanović read John Kenneth Galbraith's, The New Industrial State, which is largely the lense through which I have been watching the past 20-30 years unfold. In line with the thesis of Galbraith's book, I think the US government was an active participant (rather than a passive observer) in accelerating inequality through their policies that rewarded offshoring of jobs (tax write-offs for "restructuring"), among other decisions. How does Milanović propose billionaires and MegaCap corporations be taxed to redistribute wealth post Citizen's United? #Welcometotheoligopoly

Excellent writing!

I just want to mention two additional angles One, as a troubleshooter:

- Look for the source of the problem, fix that, then clean up. If the dam is leaking, fix the dam! You can worry about buckets later. Obligatory legend: https://time.com/archive/6796274/the-netherlands-the-hero-of-haarlem/

The other one, as someone involved with trading:

- Markets have rules. The rules evolve and need enforcement. The markets only decide inasmuch as the rules guide their participants. Governments have a role, both with rule-making and enforcement, and not just in financial markets. That's the job that we pay them taxes to do.