The Right Isn’t Reacting to Outrage; It’s Monetizing It.

Why Noah Smith is wrong about Charlie Kirk.

Sinéad here, writing while our podcast listeners anxiously await our episodic return! Pleeeease note that Alex and I have somewhat differing political ideologies. This post certainly covers a thornier topic than I usually write about (cough- Taylor Swift) so I just want to be clear: this is my opinion, and I have not discussed this with Alex, who may or may not agree with parts or all of it!

I didn’t think I’d be writing a post about Charlie Kirk this morning, especially since I’ve had Taylor Swift on my brain for the last few weeks (the UK version of Good Ideas and Power Moves is released today!), alas here we are.

I don’t typically read Noah Smith because I find his commentary largely reductive and not that interesting, but when a friend sent me his piece on Charlie Kirk’s death today, I found myself more agitated than usual.

So, here’s my rebuttal to Noah’s Noahpinion article.

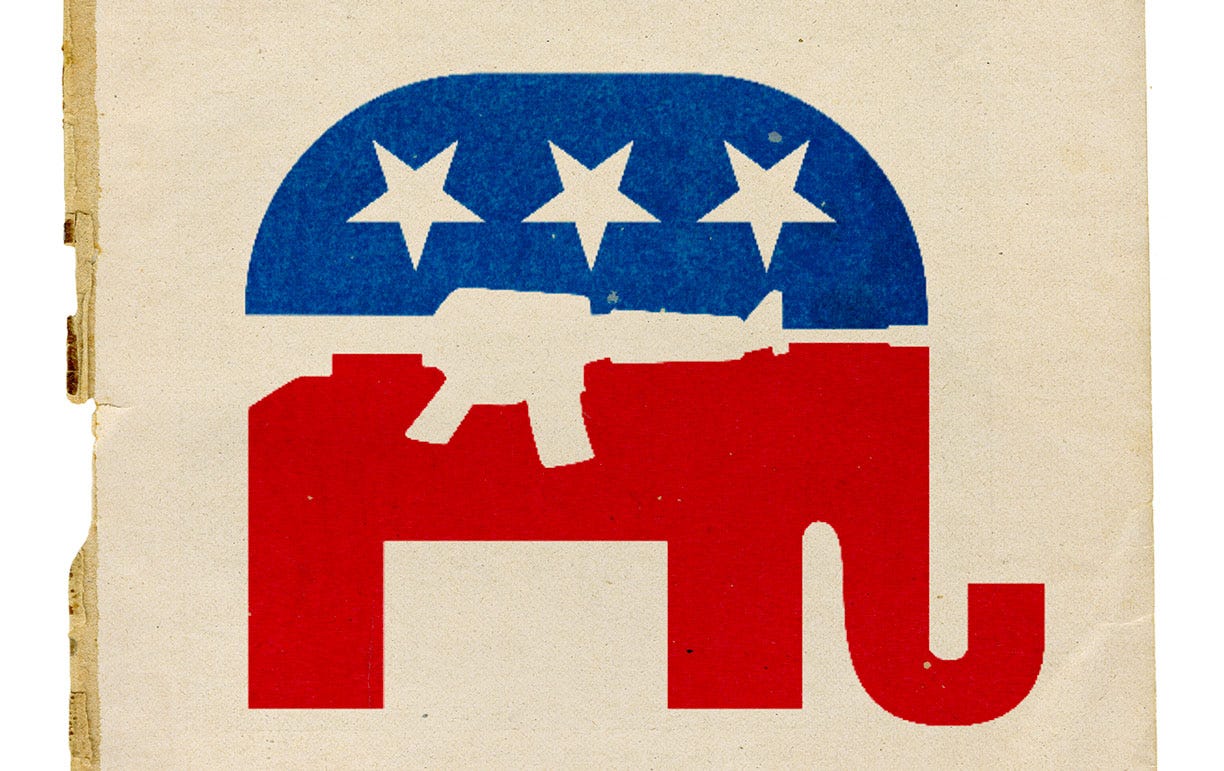

TL;DR: Noah Smith misreads America’s political violence by treating left and right extremism as symmetrical “mobs.” In reality, the far right has built a business model: fringe → influencers → elites → policy that provokes outrage, launders it through powerful figures, and monetizes it into violence and legislation. Social media isn’t a mirror of politics anymore; it is politics. And it’s been gamified into outrage in, power out.

The assassination of Charlie Kirk is horrifying. And it deserves clarity, not false equivalence.

In moments like this, the stakes could not be higher. Political violence is not just a tragedy for the individuals targeted; it’s a stress test for the entire democratic system. How we narrate and interpret that violence (who we blame, what lessons we draw, what patterns we see) determines whether we spiral deeper into reciprocal bloodletting or step back from the brink.

And yet, instead of clarity, we’re being offered comforting but misleading symmetry.

Noah Smith’s recent piece on Kirk’s killing gestures toward balance. He loosely frames the shooting as another instance of America’s “both sides” problem: online mobs on the left, mobs on the right, too much toxicity, everyone yelling too loudly, everyone needing to tone it down.

On the surface, this reads as reasonable. It feels like the sober voice in a hurricane of screaming. But it’s wrong. Profoundly wrong. And in being wrong, it makes the problem worse.

Because this misunderstanding isn’t neutral, but it does enable escalation.

By flattening the political landscape into a story of “two equally bad extremes,” Smith misdiagnoses what’s happening. He treats America’s rising tide of political violence as if it were symmetrical chaos bubbling up from the fringes of both left and right. He treats social media mobs as if they are disconnected from real institutions of power, or as if angry tweets and armed militias belong in the same category of concern. And he treats right-wing violence as if it were a reactive response to left-wing provocation, rather than what it truly is: a strategic, monetized, and institutionalized engine of political growth.

This isn’t a matter of tone, of who yells loudest online, or who needs to be more polite. It is a matter of strategy, infrastructure, and intent.

Political violence in America is not a symmetrical problem.

The far right has spent the past decade engineering a virality-driven business model; one that is perfectly adapted to the architecture of social media platforms.

It does three main things:

Aggregates attention through provocation,

Escalates fear by reframing every backlash as persecution,

Monetizes outrage through merch sales, media subscriptions, political donations, PACs, and direct voter mobilization.

It is an entire industrial ecosystem that turns anger into money, and money into power.

Anger → Money → Power

But the cycle doesn’t end there. Over time, each stage escalates because that is what capitalism and algorithms reward:

Outrage has to get sharper to capture attention (eventually turning to the subject of this article: violence).

Monetization has to get bigger to feed the machine (the “winners” and “losers” become more pronounced).

Power has to get harder, more exclusionary, to sustain itself (Umm, look at the White House’s governance model).

The endgame of that ratchet is not just noise online, but violence in the streets, billionaires financing propaganda, and movements willing to flirt with fascism.

This business model is not incidental or reactive; nor is it just a mob screaming into the void.

It is an organized machine.

By failing to grasp this, Noah Smith obscures the true mechanics of danger in three core ways:

He describes the noise, yet somehow misses the structure that creates it.

He diagnoses symptoms, but never the original disease.

In trying to hold the center, he ends up reinforcing the most dangerous asymmetry of all: the illusion that both sides are equally culpable, equally powerful, and equally violent.

And that illusion is deadly. Because when we pretend political violence is symmetrical, we give cover to those who are deliberately scaling it, refining it, and profiting from it.

Mistaking provocation for retaliation

Smith suggests that the right is simply responding to the online hate it receives from the left; that its extremism is, at some level, a reaction to left-wing vitriol. This framing paints the right as combustible but fundamentally defensive, lashing out only because they are under attack.

But that’s not how the machine works. And I would be extremely surprised if Smith has not, by now, realized that.

In reality, the modern right is not primarily a reactor, it is a provocateur.

Its first move is not to absorb left-wing anger but to manufacture it. The strategy is simple: provoke outrage, capture the backlash, and then use that backlash as evidence of persecution. The backlash becomes the fuel for escalation, and escalation is the product they sell.

This is not a cycle of mutual overreaction; it is a deliberately engineered funnel:

Aggregate → Escalate → Monetize.

Aggregate: Right-wing influencers throw out bait: memes about immigrants “invading,” soundbites about “groomers,” conspiracies about the “deep state.” These are designed to be inflammatory, not persuasive. Their goal is to attract attention, to make people mad enough to share, dunk on, or rebut.

Escalate: The predictable left-wing backlash: tweets, essays, think pieces, protests etc, is then reframed as persecution. “Look how they hate us. Look how they silence us. Look how the woke mob can’t handle the truth.” The right presents itself not as aggressors but as martyrs, embattled truth-tellers under siege.

Monetize: From there, the outrage is converted into subscriptions, merch sales, political donations, and voter mobilization. Every controversy becomes an opportunity to tighten loyalty, raise cash, and build institutional leverage.

This isn’t getting “caught up” in algorithmic rage. It is the algorithmic rage economy working exactly as intended. The right deliberately stokes the fire, knowing that anger spreads faster than nuance. Then it alchemizes that anger into money and power.

Think about how “libs of TikTok” operates: it cherry-picks fringe left-wing content, packages it for mass consumption, and then points to the angry response as proof of leftist dominance.

Or how Tucker Carlson spent years platforming the “great replacement” theory. Not to win over undecideds, but to bait liberals into outrage so that conservatives could be rallied around the idea that “they don’t want you to say the truth.”

Or how Donald Trump repeatedly makes outrageous statements knowing they will dominate coverage; when critics attack, he reframes it as elite hysteria, a badge of authenticity to his followers.

This is why the “just tone it down” solution misses the point. The right doesn’t want the tone to calm down. It wants escalation. Outrage is not an unfortunate byproduct; it’s the engine.

By casting the right as primarily reactive, Noah Smith mistakes provocation for retaliation. And in doing so, he erases the fact that right-wing actors have mastered a repeatable, monetizable playbook: one that depends on perpetual outrage to function.

Drawing a hard line between online and offline

Smith claims that online mobs are “not real” and that the vitriol of Twitter and the anonymous rage of social media are somehow detached from the serious world of politics, governance, and policy.

This is a catastrophic misread of modern politics.

In the 20th century, one could plausibly argue that “the real” was in Washington, in smoke-filled rooms, in Sunday talk shows, and that what happened on the margins of culture or in fringe newsletters didn’t matter much. But in the 21st century, the center of gravity has shifted. The internet is not commentary on politics… it is politics.

Trump, Musk, and Carlson don’t live offline. They govern online. Their power is not secondary to the state; it rivals and often eclipses it.

Foreign policy is tweeted: Trump announced major diplomatic moves (from threatening North Korea with “fire and fury” to signaling troop withdrawals) on Twitter first, treating the platform as an instrument of statecraft. Today, heads of state, foreign ministers, and even militant groups use social media posts as formal statements of war and peace.

Arrest warrants are posted to X: Police departments and intelligence services now use X and Facebook to issue alerts, warrants, and announcements, bypassing traditional press altogether. Authoritarian governments have learned the same trick: the spectacle of state power is broadcast directly to the feed.

Memes create legislation: Policy debates are increasingly downstream of viral content. “Stop the Steal” began as a hashtag and metastasized into a legislative agenda and a violent insurrection. Conservative bills restricting classroom discussion of gender or race are often copy-pasted from online panic cycles, built around viral videos and memes.

There is no longer any meaningful distinction between “Twitter” and “the state.” Online discourse doesn’t sit outside the halls of power, it sets the agenda inside them. The Senate floor now echoes with memes that originated on 4chan. Supreme Court justices cite culture-war talking points that were incubated on Facebook. Musk’s choices about moderation on X ripple outward to shape the boundaries of acceptable speech in American politics.

To describe online mobs as “not real” is like describing the printing press in 1517 as “not real.” It misunderstands the transformation of power.

When Martin Luther nailed his theses to the church door, what mattered most wasn’t the parchment, but the pamphlet wars that followed. The printing press turned a provincial theological dispute into a continental revolution.

Likewise, when FDR took to the radio in the 1930s, it wasn’t just communication. It was governance by broadcast. Radio collapsed the distance between the Oval Office and the living room, redefining how authority was performed.

Social media today is in that same lineage, except insanely faster, more chaotic, and more participatory. Its immediacy collapses the boundary between word and action, and very worryingly between meme and law.

To claim that online mobs are not “real” is to ignore that we are living through a media revolution every bit as consequential as the printing press or the invention of radio. And just as in those earlier revolutions, politics is being remade in its image.

Creating a false equivalence between extremist “mobs”

Smith gestures at “extremism on both sides,” as if America’s problem were a mirror image of angry factions hurling hatred across the internet. This framing makes his argument sound balanced, but balance here is a distortion. It erases the deep asymmetry between left-wing and right-wing extremism, both in scale and in consequence.

Yes, there is left-wing extremism in America. It exists, and it is real. We’ve seen anarchists vandalize property, Antifa-affiliated groups clash with police, and isolated individuals attempt violence in the name of anti-fascism.

During the 2020 protests, for example, billions of dollars in property damage were attributed to riots in cities across the U.S., and there have been cases (rare but real) of left-identified individuals targeting police officers or conservatives.

But here’s the crucial distinction: scale, lethality, and institutional backing.

The numbers are unambiguous:

Scale: According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), between 2015–2022, “two-thirds of all terrorist plots and attacks in the U.S. were carried out by far-right extremists.” Left-wing extremists accounted for about one-fifth, most of which involved property destruction or clashes at protests rather than mass casualty violence.

Lethality: The FBI and DHS both identify far-right violence as the deadliest domestic threat. The Anti-Defamation League’s database shows that over the past decade, “roughly 75% of ideologically motivated murders were committed by right-wing extremists,” compared to under 5% linked to the far left. Synagogue shootings, church massacres, mosque attacks, grocery store killings, January 6… these were not “Twitter mobs,” they were armed actors with explicit ideological agendas.

Institutional Backing: This is perhaps the starkest difference. Far-left extremists tend to be fragmented, suspicious of hierarchy, and lack formal support. They rarely have law enforcement, media platforms, or elected officials legitimizing them. By contrast, far-right extremists have repeatedly received cover or amplification from elites:

Proud Boys coordinated openly with political operatives during January 6.

Sitting members of Congress have echoed QAnon talking points.

Fox News and Turning Point USA laundered white nationalist conspiracies into mainstream discourse.

Sheriffs and police unions in several states have openly aligned with “constitutional militia” movements.

There is simply no equivalent infrastructure on the left. It is largely discursive and decentralized and it manifests in toxic rhetoric, anonymous trolling, or sometimes property destruction during protests. That doesn’t make it harmless (far from it), but it does make it qualitatively different.

A “radical” leftist with a burner Twitter account may call someone a Nazi or celebrate the downfall of a conservative pundit. A radical right-wing extremist, by contrast, is statistically more likely to show up at a synagogue, a Walmart, or the Capitol building with an AR-15.

But more to the point: the right’s extremism is not only violent; it is organized, armed, and in many cases institutionally protected.

Militias train openly, sheriffs pledge loyalty to anti-government “constitutional” movements, and elected officials wink at conspiracy groups like QAnon. Figures like Tucker Carlson and the late Charlie Kirk launder fringe conspiracies into mainstream talking points, providing cover and legitimacy for people further down the chain who are willing to act on them.

By contrast, left-wing radicals who cross into violence (think of isolated anarchists, Antifa-affiliated vandals, or self-styled revolutionaries) are almost always fragmented, suspicious of hierarchy, and lack institutional backing. There is no equivalent on the left to Proud Boys coordinating with political operatives, or to militias marching with tacit law enforcement approval.

Equating online trolling with coordinated acts of mass violence is sloppy, misleading, and dangerous. The idea that someone screaming “eat the rich” online is the same kind of threat as a heavily armed militia that has already tried to overturn an election is not just false, it actively obscures where the danger lies.

And yet, by creating this false equivalence, Smith gives rhetorical cover to those who would prefer to keep radicalizing, keep monetizing outrage, and keep escalating violence. When analysis refuses to name asymmetry, it strengthens the hand of the side that thrives on blurring it.

Collapsing the distinction between trolls and power brokers

Smith jumps from anonymous posts to Elon Musk, but treats them as interchangeable, as if the ramblings of a troll on 4chan and the tweets of one of the world’s most powerful men belong in the same category. This flattens the ecosystem and misses the pipeline that moves ideas from obscurity to governance.

That pipeline looks like this:

Fringe → Influencers → Elites → Policy

Fringe: Anonymous trolls and meme-makers incubate the raw material: conspiracy theories, racist jokes, ironic slogans. It’s messy, chaotic, and often cloaked in irony.

Influencers: Mid-tier figures (anonymous accounts with massive followings, podcasters, YouTubers) package those memes into repeatable narratives. They turn noise into talking points through their established, billion-dollar media accounts.

Elites: Power brokers like Trump, Musk, Carlson, and Kirk take those narratives and launder them into the mainstream. Their amplification is what transforms “something crazy online” into a legitimate political concern.

Policy: Once normalized, these narratives drive legislation, political campaigns, and even violence. “Stop the Steal” began as a hashtag; it ended with broken windows at the U.S. Capitol. Panic over “critical race theory” started with a fringe think tank memo and online outrage; within months, it became a wave of Republican state bills.

Examples of laundering in action are plentiful, but to remind you:

Trump reposts QAnon memes on Truth Social, giving a conspiratorial subculture the imprimatur of a sitting U.S. president.

Charlie Kirk platforms anti-government rhetoric at Turning Point events, turning once-fringe militia talking points into part of the youth conservative brand.

Tucker Carlson brought the “great replacement” theory from white nationalist message boards to prime-time Fox News, reframing it as a mainstream political concern.

This laundering is the unfortunate mechanism of normalization. It’s how something moves from 4chan to Facebook to Congress. And it’s deliberate: powerful figures know that giving a platform to ideas once considered too toxic creates engagement, loyalty, and mobilization.

Pretending it’s all just “mobs shouting” erases how power actually flows. Trolls may spark the fire, but elites decide which sparks get oxygen and which are ignored. The asymmetry of attention is the story. And collapsing trolls and power brokers into the same bucket is to miss the design of the machine entirely.

What We Should Actually Be Talking About

This moment demands more than platitudes about “toning down the rhetoric.”

The danger is not that Americans are rude to each other online; the danger is that extremist ecosystems are systematically converting outrage into policy and then violence and eventually power.

(Dare I mention the laughable irony here that this is also the week that Nick Clegg’s - of all people- “How To Save The Internet” book is launched?).

Understanding the structure of what is happening right now requires structural clarity, not moral hand-wringing. And I find it puzzling that Smith cannot dig deep enough to uncover this.

But while he won’t do it, I will. Here’s what that clarity looks like:

Draw sharp distinctions between rhetoric and real-world violence: Anonymous trolling is not the same as a militia attack, and confusing the two obscures where the danger lies.

Understand how power moves through platforms: From fringe memes to influencer talking points to elite amplification to policy outcomes, the pipeline must be mapped clearly.

Hold elite actors accountable for laundering extremism: Sure, the trolls light the spark, but it’s Trump, Carlson, Kirk, and Musk who fan it into an inferno.

Teach media literacy around algorithmic amplification: Ordinary users need to recognize that engagement-driven platforms reward the most extreme content, not the most representative. We’ve been saying this for years.

Pressure platforms to disincentivize stochastic terrorism: When design choices amplify hate and conspiracy, violence follows. Platform owners must be treated as political actors, not neutral hosts. I spent a significant amount of time at MIT working on exactly this, before realizing that people like Nick Clegg is why it’ll never happen.

So Yeah… Missing the Plot Has Consequences

Noah Smith is not trying to defend the far right, as far as I am aware. But by flattening distinctions and clinging to outdated models of political power, his analysis makes it harder to see what’s actually happening.

Is he doing this on purpose? I honestly don’t think so, but it does then make me question how he is taken seriously as a commentator by… anyone.

This issue is not a matter of “both sides.” It is not a matter of civility. It is not even a matter of rhetoric alone. Instead, it is about a deliberate strategy that uses platforms as engines of radicalization, monetization, and political capture.

Sometimes, the victims of that political capture even come from within the same party itself.

Republican incumbents who fail to regurgitate the most radical talking points face well-financed primary challengers; conservative pundits like Charlie Kirk have been attacked by harder-right factions for not being extreme enough; even figures like Mike Pence found themselves branded traitors overnight as he was hunted down on January 6th.

The machine does not merely target ideological opponents, as we are seeing: it also disciplines its own.

So in a moment this volatile, clarity is responsibility.

And responsibility begins with rejecting bothsidesism, naming the asymmetry of violence, and recognizing that social media is not a mirror of our politics. it is our politics.

And it has long been gamified to outrage political ideology into existence.